Most Recent Visit: July 2021

Located just 5 kilometers off the coast of mainland Asia Minor (modern Türkiye) and about 18 kilometers from the famous city of Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum), at the entry of the Sinus Doridis/Sinus Ceramicus (modern Gulf of Kerme) is the island of Kos. According to myth, the founder of the settlement of Kos on the island was Merops, who named it after his daughter, Kos. It was sometimes referred to as Meropian Kos or even just Meropis. Another myth places the island as the birthplace of Leto, mother of Apollo and Artemis. Her father, Coeus was said to have been the earliest inhabitant of Kos, as noted by Tacitus, and would seemingly have been the namesake in this case. Hercules was said to have been shipwrecked on the island and fought with Antagoras, son of Poseidon and the local Koans. Later, the Koans would claim descendance from Hercules.

The island was inhabited since at least the Mycenean period, and following that was colonized by the Dorians in the 11th century BCE. Specifically, tradition held that the colonists came from Epidaurus, and that the worship of Asclepius was brought to Kos by those means. It was around this time that a federation of Dorian cities called the Doric Hexapolis was established along with 5 other Dorian cities in the region that included Lindus, Ialysus, and Camirus on Rhodes and Cnidus and Halicarnassus in Caria. The Koans are mentioned in the Illiad as participating in the Trojan War on the side of the Greeks, and around the same time being engaged in conflict with the Carians.

The Doric Hexapolis was dissolved in the middle of the 6th century BCE, and by the end of the 6th century BCE, Kos had fallen under Persian control. Following the Battle of Mycale on August 27-28 479 BCE, one of two simultaneous battles that ended the Second Persian Invasion of Greece, the Koans rebelled against the Persians and broke free of Persian hegemony. Circa 460 BCE, the influential physician Hippocrates was born on the island and likely learned his craft at the Asclepieion on the island. Kos entered into the Delian League not long after ejecting Persian rule and would go on to support Athens in the Peloponnesian War. Around 410 BCE the island was conquered by Lysander and occupied by Sparta. Kos remained under Spartan influence until around 394 BCE, when it would again enter into an alliance with Athens. A period of internal instability followed on the island and in 366 BCE there was a synoecism and the various settlements of the island united to establish a common political and administrative center around a natural harbor at the base of the promontory of Scandarium in the northeast of the island, where the modern town of Kos is located. This city would be run democratically, laid out in a Hippodamian plan, and named Kos and likely supplanted the older Kos Meropis in the same area.

Kos is traditionally believed to be the origin of the silk fabric and the fine translucent garments made from it known as coa vestis. These are first mentioned by Aristotle in the 4th century BCE and later by Pliny the Elder, who claims the process was developed by a woman named Pamphile, daughter of Platea. Kos fought along with Chios, Rhodes, and Byzantium against Athens in the Social War from 357 to 355 BCE, but during or shortly after the war the island came under the control of King Mausolos of Caria. When Halicarnassus fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BCE, Kos came under the hegemony of the Macedonians. The famous painter Apelles, who produced portraits of Alexander, was born in Kos at some point prior to Macedonian control of the island. Following Alexander’s death, Kos was initially in the territory of Antigonus I Monophthalamus, but by 309 BCE it had been taken by Ptolemy I Soter. His son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus was born there that same year.

Under the Ptolemaic Kingdom, Kos retained a large degree of autonomy. During the Hellenistic period, Kos became especially renowned for providing judges to mediate disputes in other Greek cities around the Aegean. The city flourished as a center of trade and learning and was also notable for the wine, dye, and amphora produced there. Around 258 BCE, Ptolemy II lost a naval battle to Antigonus II Gonatas which lead to the island falling under Macedonian hegemony. The great Asclepieion sanctuary outside of the city was completed in 242 BCE and recognized by the other Hellenistic states as an inviolable panhellenic sanctuary. In the late 3rd century BCE, the Koans would enter into the sphere of influence of nearby Rhodes and by the early 2nd century BCE, Kos was under Roman hegemony. The Koans remained steadfastly in support of Rome and were rewarded (perhaps after the submission of Greece in 146 BCE) with civitas libera status. In 88 BCE, early in the First Mithradatic War, Kos was conquered and sacked by Mithradates VI Eupator. Appian suggests, however, that Mithradates was welcomed by the Koans and they willingly gave him the treasury of Cleopatra III. The Poet Meleager of Gadara settled in Kos and died there in the mid-1st centuy BCE. From about 41 to 31 BCE, the island was ruled by a tyrant allied with Marcus Antonius who was presumably deposed after Antonius’ death. Apelles’ painting of Aphrodite Anadyomene was demanded by Augustus as part of a levy on Kos for their support of Antonius against him.

During the time of Augustus, Kos was made part of the province of Asiana and lost its status as civitas libera. The island also suffered a notable earthquake about 6 BCE. Under Claudius, Kos was granted immunity from taxes. This was likely due to influence from his personal physician, Gaius Stertinius Xenophon, who was born on Kos and would later be implicated in Claudius’ poisoning death. The city continued to be relatively prosperous as a production and trade center through the Roman period and possibly regained their civitas libera status around 79 CE (but definitely by the reign of Caracalla). In 142 CE an earthquake devastated the city and island and Antoninus Pius is recorded as having contributed directly to the recovery of Kos. In late antiquity is was reorganized into the province of Insulae, along with many of the other Aegean islands. Further earthquakes hit in the island in 469 CE and 554 CE, as well as effects from the July 365 earthquake off Crete.

Getting There: Kos is serviced by a small international airport that has about 25 flights a day during the summer to/from various destinations in Europe. The airport is a bit out of the main town, but there is regular bus service between the port and the airport. There are also ferry connections to various islands, most notably Rhodes, but also to Bodrum.

The archaeological remains of the settlement of Kos are fairly extensive. In addition to several organized archaeological areas, there are a number of open access areas that can be freely visited or fenced areas with no direct access that can be observed from public grounds.

A relatively arbitrary place to start are the so-called Port or Harbor Baths. These are located north of Irodotou at its intersection with Omirou, though they are not accessible from this side. These are not part of an incorporated archaeological area, but are fenced along Irodotou. There is access from the plaza at the southwest corner of the intersection of Megalou Alexandrou and Akti Kountourioutou, near the statue of Hippocrates. These are the oldest extant baths in Kos, with an initial construction dating back to the 3rd century BCE. They continued to be used and altered through the Roman period, but suffered heavy damage and probably fell out of use following the 469 CE earthquake.

While the remains of the baths are pretty significant, there unfortunately does not seem to be much information on what is actually here. It’s one of the few points of archaeological interest in the town that does not have even a basic information board. Some larger ashlar blocks, presumably from the earlier phases of the building are visible in a few places, while the clearly Roman brickwork arches are visible in others. There are a number of these that are presumably part of the hypocaust or water channeling systems that would have allowed the baths to function in the Roman period.

A few blocks to the southeast, accessible from Panagi Tsaldari between Verroiopoulou and Akti Kountouriotou are the so-called Northern Baths. The bathing complex dates to the 3rd century CE and seemed to have been an addition to an existing adjacent gymnasium dating to the Hellenistic period and incorporating a structure dating to the 4th-3rd century BCE. Like the Port Baths, there are definitely some substantial remnants of the bathing complex, but there is not much information to contextualize what is here. There’s a fairly densely built-up area just of Panagi Tsaldari, but farther into the lot the remains are a little sparser, though this is also where the incorporated blocks of the 4th-3rd century construction can be seen. Inscriptions found here suggest activity of a cult of Hermes Eumelus. There is a small informational sign toward the central area of the baths.

A couple more blocks to the east, on the west side of Platia Eleftheria, is the Archaeological Museum of Kos. The museum is open Wednesday through Monday from 8:00 to 20:00 in the summer (April through October) and from 8:30 to 15:30 the rest of the year. The museum is closed on Tuesday year-round. Admission is 10 Euros.

The museum is not especially large, particularly at the current price point (though it was only 6 Euros when I visited), but it is absolutely jam packed with amazing objects. Right after entering the museum is a faux atrium that features at center a Roman mosaic of Asclepius arriving in Kos as Hippocrates observes. The atrium is lined by statues that include Hygeia, Hermes Eumelus seated on a rock, Artemis, and Dionysus. Some of these statues, including another of an indistinct woman, have significant traces of pigment remaining on the statues. The statue of the woman has the coloring for almost the entire trim of her garment. An adjacent room with more statuary (mostly from the odeon) features a statue sometimes identified as Hippocrates.

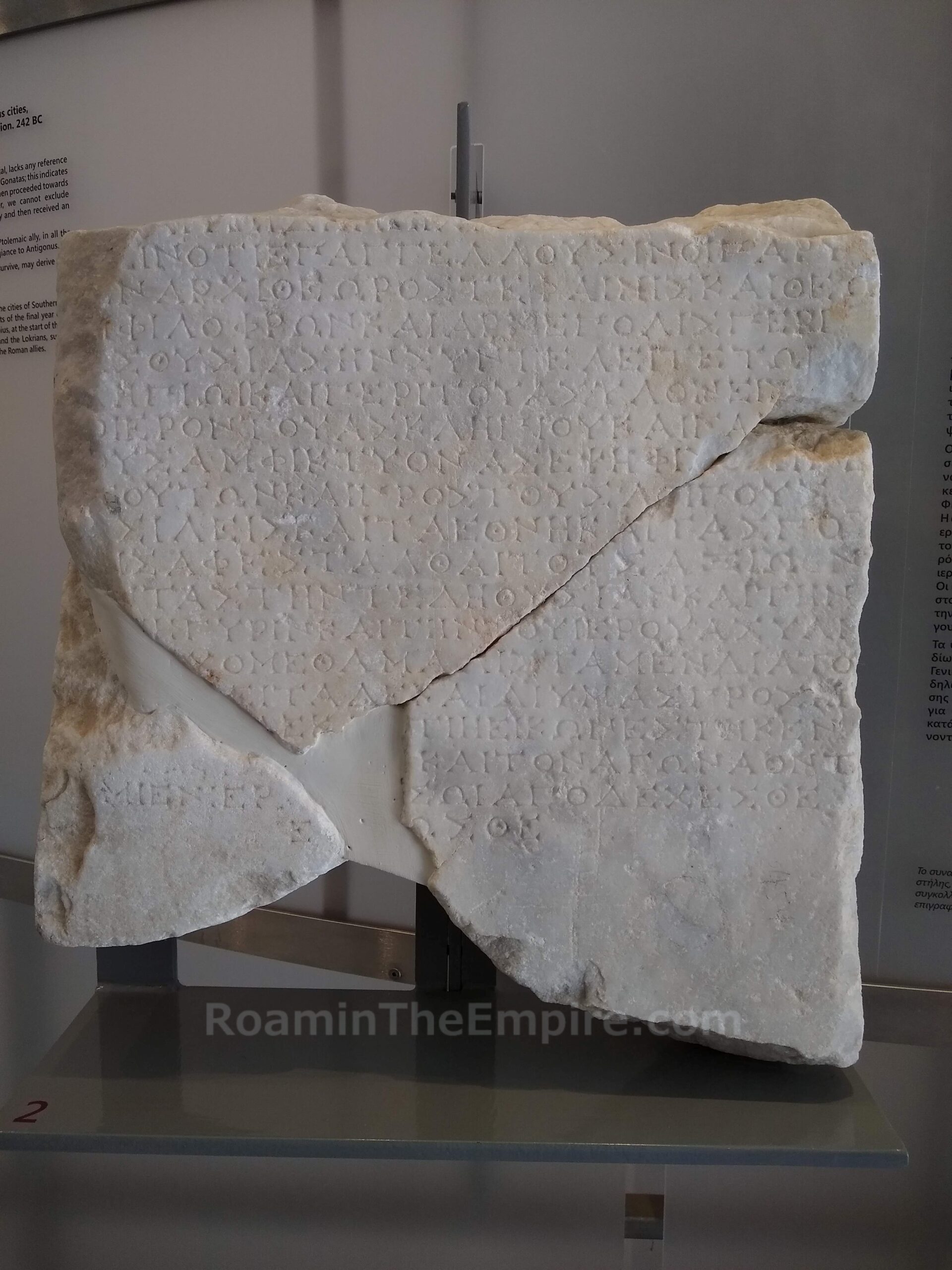

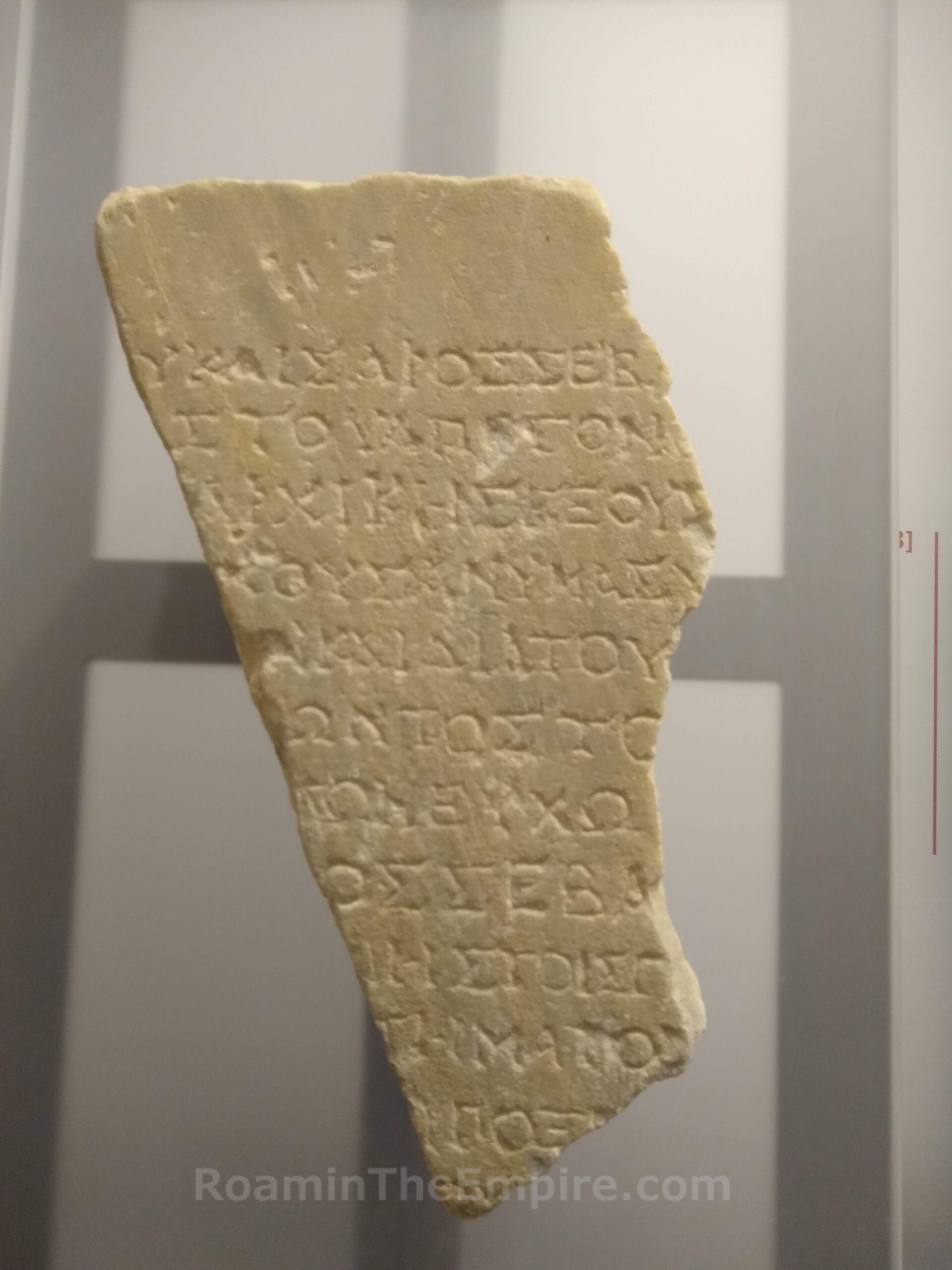

The collection also features lots of votives and other objects from sanctuaries in the city and around the island. Other highlights include a series of imperial Roman bronze statuettes found in the agora (including some from the so-called House of the Bronzes). There’s also a collection of coinage. One area in which the museum was surprisingly light was inscriptions, as there were only a few. Though there is a decent collection of inscriptions housed at the Asclepieion. Again, despite it being a relatively small museum, it still took me nearly two hours to go through. The objects in the museum are well labeled with both Greek and English information.

Backtracking to the Northern baths, essentially kitty-corner to the block that houses the baths is the block that houses the stadium. The stadium occupied a still mostly undeveloped block of land bounded by Verroiopoulou on the north, Panagi Tsaldari on the east and south, and Megalou Alexandrou on the west. Leoforos Eleftheriou Venizelou cuts through the tract near the south end. Construction of the stadium apparently began in the 3rd century BCE, but it was not finished until the 2nd century BCE. Improvements during the Roman period included the addition of seating for dignitaries as well as some additional seating on the west side of the stadium.

Not much is visible of the stadium, despite its size and prominence. The most impressive remains of the stadium are at the southeast corner of Verroiopoulou and Megalou Alexandrou. This is where the starting line and the hysplex were found. The area isn’t accessible but can be seen from public areas. The bases of a number of these mechanisms that marked the starting position of the races can be seen, and even a few of these have fluted posts that resemble small columns that extend upward. Some remnants of the eastern seating of the stadium are visible facing south on Leoforos Eleftheriou Venizelou near the intersection with Panagi Tsaldari.

A block east of the stadium on Ah. Passanikolaki (which is the street north of Leoforos Eleftheriou Venizelou) is a small fenced in area at the northwest corner with Ethnarchou Makariou. I’ve been unable to find any real indication of what is present at this location, and honestly it looks like it might be a bit later in construction than the Roman period. There’s no direct access into the fenced area and there is no information of any kind on site.

Continued In Kos Part II

Sources:

Appian. Historia Romana, XII.4.23, XII.17.115-117.

Aristotle. Ton Peri Ta Zoia Historion, 5.19.

Arrian. Alexandrou Anabasis, 6.11.

Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae, 12.77, 13.71.69, 15.32, 15.38.

Demosthenes. Yper Tis Rodion Eleftherias, 27.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 5.54.3, 11.3.8, 14.84.3, 15.76.2, 16.7.3, 16.21.1, 19.68.3, 20.27.

Evagrius Scholasticus. Ekklisiastiki Istoria, 2.14.1.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Herodotus, Historiai, 1.144, 7.164.

Homer. Illiad, 2.2.677.

Hyginus. De Astronomia, 2.16.

Jerome of Stridon. Chronicon.

Livadiotti, Monica. Due edifice termali a Coo città: tipologie a confronto.

LIvadiotti, Monica. “The Infrastructure of a Hellenistic Town and Its Persistence in Imperial Period: The Case of Kos.” Thiasos, No. 7.2 (2018).

Ovid. Metamorphoses, 7.357.

Parker, Robert. “The Cult of Aphrodite Pandamos and Pontia on Cos.” Kykeon: Studies in Honour of H.S. Versnel. HFJ Hortsmanshoff, HW Singor, FT Van Straten, and JHM Strubbe (eds.), Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 3.23.6, 8.43.

Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis, 5.134, 11.26-27, 13.5, 14.10.1, 15.18.2, 20.100.1, 23.14.1, 27.27.1, 29.4, 35.79, 35.92, 35.161, 36.20

Polybius. Historiai, 30.7, 37.

Rocco, Giorgio and Monica Livadiotti. “The Agora of Kos: The Hellenistic and Roman Phases.” The Agora in the Mediterranean from Homeric to Roman Times: International Conference Kos, 14-17 April 2011. A. Giannikouri (ed.), Athens, 2011.

Scafuro, Adele C. “Koan Good Judgemanship: Working for the Gods in IG XII.4.1 132.” Greek Epigraphy and Religion: Papers in Memory of Sara B. Aleshire from the Second North American Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy. Emily Mackil and Nikolaos Papazakadas (eds.), Leiden:Brill, 2016.

Sherwin-White, Susan M. Ancient Cos: An Historical Study from the Dorian Settlement to the Imperial Period. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen, 1978.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographica, 12.8.6, 14.1.15, 14.2.19, 15.1.3.

Tacitus. Annals, 2.75, 4.14, 12.61.

Thucydides. Historiai, 8.41-45, 8.108.