Most Recent Visit: June 2022

The area that the Romans would eventually settle as Colonia Ulpia Traiana, near the confluence of the Rhenus (modern Rhine) and Lupia (modern Lippe) rivers, was sparsely inhabited by local groups for at least the preceding two millennia. There does not seem to have been any large settlements identified in the immediate area. At the time of the Roman’s arrival, the future site of the city was in the territory of the Cugerni. Roman hegemony came to the area following Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul in the 50’s BCE, essentially incorporating all the territory west of the lower Rhenus. The late 1st century BCE saw increasing tension between the Romans and the Germanic groups to the east along the Rhenus frontier. In 16 BCE, the Roman proconsul of Gaul, Marcus Lollius, suffered a humiliating defeat in which Legio V Alaudae’s eagle was lost to a group of Germanic raiders who had killed Roman citizens east of the Rhenus and then crossed over to raid Roman territory in the west.

Lollius’ loss and the general threat of Germanic raids led to Augustus’ decision to fortify the Rhenus frontier, which resulted in the establishment of the Castra Vetera double legionary fortress by Drusus circa 13 BCE (referred to as Castra Vetera I to distinguish it from a later fortress built there). The location of the camp is south of modern Xanten, just to the north of the modern town of Birten (which is a name derived from Vetera), though nothing of the actual camp remains visible. It is not clear which legions were initially stationed at Castra Vetera, but it was used as a base of operations for Drusus’ campaigns into Germania in the following years. It has been suggested that Legio XVIII may have been stationed here, based on the funerary monument of a soldier from that legion found in Birten. A modest civilian settlement of the Cugerni grew up nearby, seemingly called Cibernodurum.

Following the Roman defeat at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE and the recognition that Roman designs for the land beyond the Rhenus were at least temporarily on hold, Castra Vetera was significantly upgraded as part of the Limes Germanicus. Around this time Legio V Alaudae and Legio XXI Rapax were stationed at the fort. Military operations continued beyond the Rhenus in the following years under Tiberius and Germanicus, but without the goal conquering territory. A bridge across the Rhenus was located at Castra Vetera, and Tacitus relates an incident in 15 CE in which the bridge was nearly destroyed by the Romans fearing a Germanic attack. Only through the intervention of Agrippina the Elder was the bridge preserved and the Roman legions operating across the Rhenus able to return without being trapped.

The fortress was rebuilt and strengthened a number of times over the first half of the 1st century CE, including sometime around 30 CE when an amphitheater was built south of the camp. As legions were pulled for Claudius’ invasion of Britain in 43 CE, Legio XXI Rapax was replaced by Legio XV Primagenia at Castra Vetera. Around this time the camp was again rebuilt, this time trading wood and earthworks for stone. Among the turmoil of the civil wars in the wake of Nero’s death in 69 CE, the tribe just to the north of Castra Vetera, the Batavi, rebelled against Roman rule. The two legions at Castra Vetera were sent to quell the rebellion but were defeated and returned to their camp. The Batavi, under the command of Gaius Julius Civilis, pursued the Roman armies and laid siege to Castra Vetera in September of that year. Cibernodurum, which seems to have been granted municipium by the time of Nero, was destroyed early on by the garrison to prevent it from being utilized in the siege. Faced with the prospect of Roman reinforcements coming to break the siege, the Batavi feigned an attack on Moguntiacum (modern Mainz), drawing away the reinforcements and allowing the siege to continue. As the siege stretched into 70 CE, supplies began to run out and the commander at Castra Vetera offered to surrender the fort in return for safe passage to leave. This was agreed to by Civilis, but the armies were ambushed after leaving the fort and Castra Vetera was destroyed.

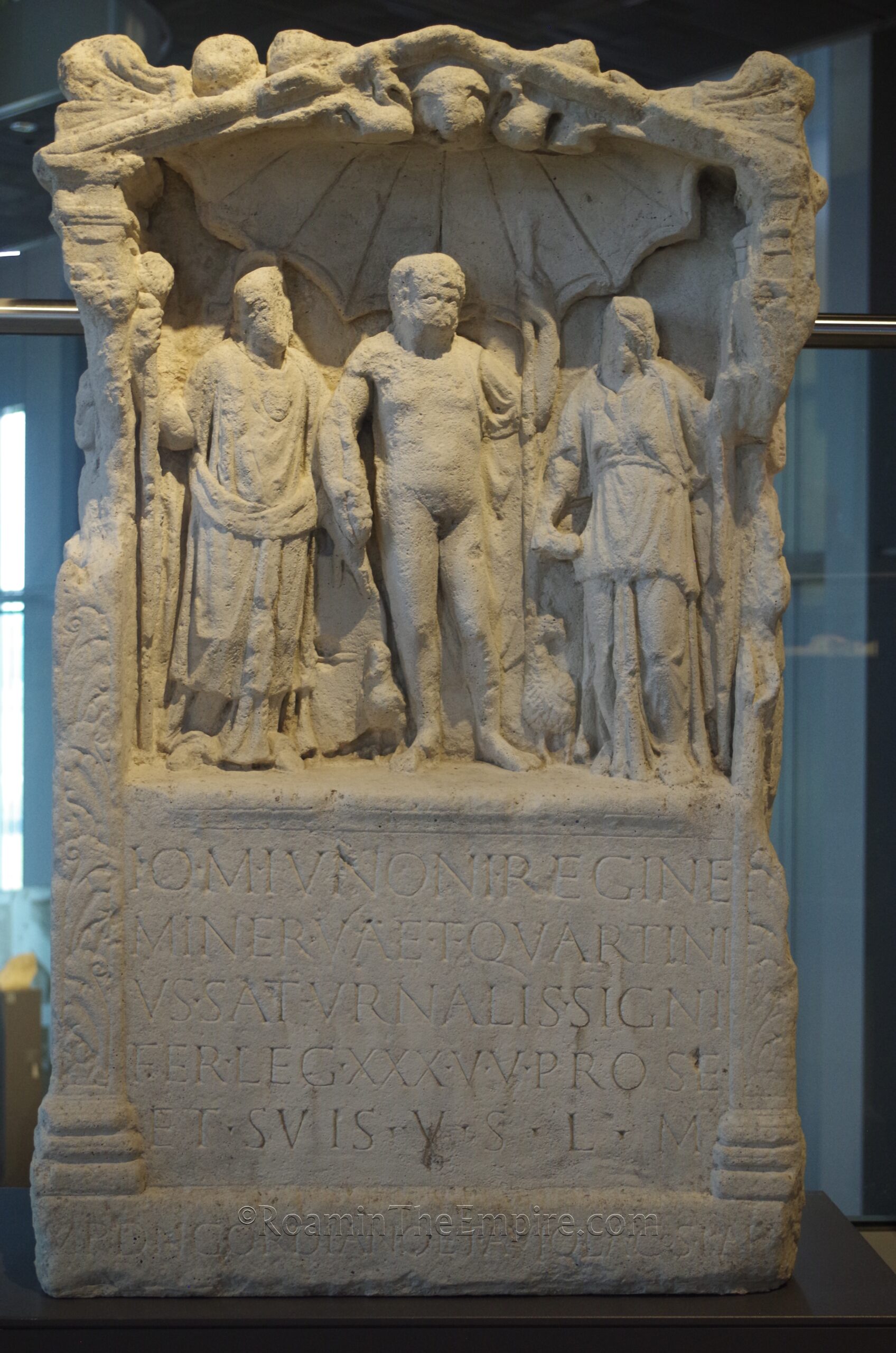

Following the restoration of order in the area, a smaller legionary camp was constructed by Legio XXII Primagenia to the east of the old camp. It was located on what is now the Bislicher Insel wetlands reserve, of which there is again nothing to see of the remains of the camp. In 85 CE the province of Germania Inferior was established over the area of Castra Vetera and Cibernodurum by Domitian. In about 105 CE a colonia of at least 10,000 legionary veterans was established at Cibernodurum and the settlement was reorganized and renamed, bearing the name of the emperor; Colonia Ulpia Traiana. By 110 CE, Legio XXII Primagenia was replaced by Legio VI Victrix at Castra Vetera. In 122 CE, Legio VI Victrix was transferred out and Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix was fittingly stationed there. Colonia Ulpia Traiana was continuously developed over the 2nd century CE, becoming the second most important city in the province behind the capital, Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (modern Köln). A formidable circuit of defensive fortifications was constructed around the city.

Colonia Ulpia Taraiana seems to have entered a period of decline in the 3rd century CE. The city was attacked by Germanic raiders in 260 CE, but escaped serious damage. Another Germanic raid in 275 CE, however, resulted in heavy damage to the city. The civilian settlement was largely abandoned and in the early 4th century CE seems to have been repurposed as a legionary fortress for Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix. A new set of walls were constructed around the center of Colonia Ulpia Traiana and it was known as Tricensima, of the thirtieth. Around the middle of the 4th century CE, Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix was transferred elsewhere and by the middle of the 5th century CE, the site was effectively abandoned.

Getting There: There are frequent trains (at least once an hour) to Xanten from the two larger cities in the area; Köln and Dortmund. Neither offer direct connections, though, both routes connect through Duisburg. The trip is nearly identical from both cities; taking between 1.5 and 2 hours and costing 22 Euros or greater depending on the train. There’s ample free parking at the archaeological park and a private vehicle allows easy visitation to a couple stops outside the archaeological park.

Pretty much all of the relevant and visible archaeological remains for Colonia Ulpia Traiana/Castra Vetera are contained within the main archaeological park with one notable exception; the Castra Vetera amphitheater. Located just of the Rheinberger Straße between Xanten and Birten, a little more than a kilometer to the north of Birten are the remains of the amphitheater that was constructed on the south side of Castra Vetera around 30 CE. Today, the amphitheater is a music venue and a park; it doesn’t seem to have any real hours of operation and may or may not be open at any given time. It was open when I visited, fortunately. The original amphitheater was constructed of wood and earth, so only the earthen shape of the amphitheater is now visible; there are no masonry constructions. Even that is fairly overgrown (at least in the summer) so even most of the directly visible earthen construction was not actually visible when I visited, just the shape. There’s no information about the amphitheater on site, but there are a few signs about the legionary camp in German.

Another 4 kilometers north on the Rheinberger Straße is the main entrance to the LVR-Archäologischer Park Xanten. The archaeological park is open daily all year, though hours vary by season. In the summer (March through October) the park is open from 9:00 to 18:00. In November it is open 9:00 to 17:00 and December through February from 9:00 to 16:00. Admission is 11 Euros. It’s worth noting right off the bat that the archaeological park is a heavy mix of reconstructed buildings interspersed at times with the visible remains of the ancient buildings upon which the reconstructed buildings are based. It seems to be a fairly common thing in this part of Europe.

On approaching the entrance to the archaeological park, the reconstructed fortifications are the first thing one encounters. The main circuit of walls were heavily damaged or destroyed in the 3rd century CE, and what is visible now are reconstructions of the original fortifications from the foundation of the colony. Outside the park and the walls, defensive ditches have also been reconstructed. Inside the park, the practice of reinforcing the interior of the walls with an earthen mound has been replicated. The original circuit of the walls ran about 3.4 kilometers with 22 towers and 3 main entrance gates. About 1.4 kilometers of this circuit has been laid out between a small portion of reconstructed walls in the northeast corner as well as the use of tall hedges to mark the course. Nine of the towers, predominately around the north side of the walls and adjacent stretches of eastern and western walls, and one of the main entrance gates have been reconstructed. The actual reconstructed walls, which can be partially traversed, start just inside the entrance and wrap around the northeast corner of the settlement.

A short walk along the walls from the entrance is one of the main monuments of the archaeological park, the amphitheater. The original amphitheater of Colonia Ulpia Traiana was constructed of wood and was later expanded. Around the beginning of the 2nd century CE it was rebuilt in stone with the capacity estimated to have been about 10,000 spectators. The amphitheater is pretty heavily reconstructed with the entirety of the interior wall as well as all the seating areas being reconstructions. The support pillars visible in the eastern half of the amphitheater are more representative of what was present following the excavations, though these two have been conserved and stabilized. There are a few informational exhibits within the reconstructed part of the amphitheater, including some copies of reliefs related to Nemesis. Another notable object here is, on the north side of the amphitheater, a reconstruction of a Roman crane.

Continued In Colonia Ulpia Traiana Part II

Sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus. Res Gestae, 18.2.4.

Bowman, Alan K., Peter Garnsey, and Dominic Rathbone (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XI: The High Empire, A.D. 70-192. New York City: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Dando-Collins, Stephen. Legions of Rome: The Definitive History of Every Imperial Roman Legion. New York: Quercus, 2010.

Derks, Ton. “Ethnic Identity in the Roman Frontier: The Epigraphy of the Batavi and the Other Lower Rhine tribes.” Ethnic constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition, Ton Derks and Nico Roymans (eds.), Amsterdam University Press, 2009.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Tacitus. Annals, 1.45, 1.68-70.

Tacitus. Historiae, 4.18-36, 4.57-62, 5.14.