A few kilometers outside both the modern and ancient city of Kos, is the Asclepieion complex. It is located just southwest of the village of Platani, off Agiou Dimitriou. The site doesn’t have an address, really, but it is well signposted from Kos and the main east-west road on the island (Eparki Odos Ko-Kefalou) that runs about a kilometer north. The Ascelpieion is open daily from 8:00 to 20:00 in the summer (April through August) and has a gradual reduction of hours of half an hour every 15 days in September and October to an 18:00 closing time. Admission is 15 Euros.

A likely apocryphal tradition held that the Doric settlers to Kos were from Epidaurus, and it was this connection to Epidaurus and its own Asclepieion that brought the worship of Asclepius to Kos. Likely the cult of Asclepius was imported to Kos at a later date, probably not earlier than the 5th century BCE. It may have been imported from Epidaurus, or more likely Trikka. The site of the Asclepieion seems to have held religious significance since at least the Mycenean period, between the 16th and 11th centuries BCE. A grove of cypress trees sacred to Apollo, father of Asclepius, seems to have existed at the spot of the Asclepieion since the 6th century BCE. Epigraphic evidence suggests the presence of an organized sanctuary here in the 5th century BCE, though they do not record the deity to which it was dedicated. An inscription found at the site of the upper terrace and dated to the late 5th or early 4th century CE records the worship of Paeon, which is sometimes used an epithet of Apollo or Asclepius and sometimes a used to indicate a totally separate deity or healer.

The core of the Asclepieion seems to have been constructed all at once, as opposed to starting as a smaller sanctuary and growing over time, between about 278 BCE and 242 BCE. The sanctuary must have been completed by 242 BCE because it was that year that the Koans requested asylia for the Asclepieion and recognition as a panhellenic sanctuary, which was granted. The panhellenic Asclepieia Megala games in honor of Asclepius and the establishment of the sanctuary were also instituted and recognized that year. A major building and renovation project occurred in the 2nd century BCE, when several structures were added within the sanctuary and others were renovated and expanded. These renovations were possibly financed by Hellenistic rulers, though the records of payment don’t survive.

When Mithradates IV Eupator enacted the Asiatic Vespers and conquered the island at the outset of the First Mithradatic War in 88 BCE, a number of Romans sought asylum at the Asclepieion. Mithradates reportedly respected the asylia of the sanctuary and did not demand or take the Romans by force. Prior to the Battle of Actium, an admiral of Marcus Antonius named Turullius cut down most of the sacred cypress grove of Apollo located on the upper terrace of the Asclepieion in order to construct ships needed for the battle. Turullius was surrendered to Octavian following the battle and in 30 BCE he was returned to Kos and executed by the Koans for the sacrilege of cutting down the sacred grove.

The sanctuary remained active and important in the Roman period. It doesn’t seem to have suffered much from the 6 BCE earthquake, as there is no record of repairs. In 23 CE, the Koans requested that the asylia of the sanctuary be confirmed by the Senate. The rise of the Kos born and trained physician Gaius Stertinius Xenophon to the rank of personal physician of Claudius benefitted the Asclepieion as Xenophon financed the third major building phase at the sanctuary with the construction of a new water supply from the springs at Bournia as well as the erection of a library and a temple dedicated to Asclepius, Hygeia, and Epione to commemorate his priesthood. Though it may have escaped damage in the 6 BCE earthquake, the Asclepieion was severely damaged in the 142 CE earthquake and the sanctuary required extensive rebuilding, including a new temple.

Some more buildings were added in the late 2nd or 3rd century CE; a baths and latrines on the upper terrace. The sanctuary continued functioning through the 4th and into the 5th century CE, until the earthquake of 469 CE likely caused some degree of damage. Sometime in the 5th century CE, a small Christian church dedicated to the Virgin of Tarsos was constructed on the upper terrace. The earthquake of 554 CE completed the abandonment of the sanctuary and the site was heavily spoliated through the next several centuries.

The Aclepieion is divided into three terraces that made use of the existing landscape of the site. There is a lower level below the lower terrace, which is where one enters into the archaeological area. On this lowest level, adjacent to the monumental staircase that leads up to the lower terrace, are the remains of a complex that included a bathing area and a hospitium for pilgrims seeking healing at the sanctuary. This structure was added in the building phase that followed the 142 CE earthquake, which is somewhat apparent in the mixed use of building materials, probably making use of some of the damaged material from the earthquake. Some bases of pilae from the hypocaust system are visible in at least one of the rooms. The apsidal areas where water pools were located can also be discerned. A natatio is present on the southeast side of the complex.

The staircase led up to a monumental propylon that allowed access to the lower terrace of the Aclepieion. This terrace survived as the arrival point for pilgrims, where they would stay and would engage in ritual cleansing acts. This is also where physical treatment might take place. Some significant elements of the north foundations of the propylon remain flanking the staircase, but very little of the superstructure on the actual terrace; just a few bits of the foundation. It dates to the initial phase of construction of the sanctuary in the early to mid-3rd century BCE. The northern, eastern, and western sides of the terrace were enclosed by a stoa and covered portico also dated to the initial phase of construction. The remains of the stoai are pretty fragmentary; some elements of the north stoa are visible, though there is also a lot of scattered debris. An interior wall running nearly the entire length is fairly robust. Elements of the western stoa are present, particularly at the south. The eastern stoa might be the most complete, with nearly the entirety preserved to some degree and some of the walls preserved up to a couple of courses of stone.

At the northeast side of the terrace is a large bathing and hospitium complex, much larger than the one below this terrace. This was another structure built sometime after the 142 CE earthquake. Unfortunately, the complex is mostly inaccessible with gates and ropes limiting access. The two large caldaria on the south side of the complex can be seen from a path running outside the complex on that side, as the exterior walls are not well-preserved at that point, but many of the other rooms are obscured by the significant remaining walls. There is some access to the vestibule area, and a room with painted wall decoration is visible off the vestibule. The baths are built partway off the terrace on a platform. There is a stairway access point (not accessible now) from below the lower terrace.

The south side of the lower terrace is delineated by a large retaining wall for the middle terrace. Large arched alcoves in which statues were placed were added into the wall to the east of the monumental staircase to the middle terrace, which is notably not directly in the center of the terrace, in the 1st century CE. The second niche from the staircase contains a still-functioning fountain that emerges from a spout decorated with a relief of Pan. This was probably used for cleanings rituals taking place on the terrace. Immediately west of the staircase is another niche that contains a dedication to Gaius Stertinius Xenophon. Another triple alcove feature exists west of this, which appears to be another water storage feature. An external basin is located a few meters past these. At the southwest extent of the western stoa, a latrine was added in the post-142 CE construction phase, but it is now mostly obscured by a tree growing out of the middle of it.

The monumental staircase leads up to the middle terrace, the smallest of the three. Directly in front of the staircase is an altar, the core of which predates the sanctuary with a late 4th century BCE dating. An inscription records that it was dedicated to Halios, Hamera, Machaon, and Hecate. By the early 3rd century BCE it had been partially destroyed and was then incorporated into the altar for the temple immediately to the west, the so-called Temple B. The 3rd century BCE altar was apparently adorned with sculpture attributed to the sculptors Praxiteles, Kephisodotos, and Timarchos. The altar was again reconstructed in the 2nd century BCE renovations of the sanctuary. Temple B was earliest temple constructed in the sanctuary, dating to the first phase of construction. An inscription indicates that it was dedicated to Asclepius. Apelles’ Aphrodite Anadyomene was said to have decorated the pronaos of the temple before Augustus demanded it as payment. The crepidoma of the temple is well preserved, as is a bit of the cella. A couple of columns have been reconstructed at the front.

Just to the south of this temple is Building D, constructed at the same time as Temple B and divided into two distinct areas. It has long been suspected that this may have originally functioned as an abaton, where pilgrims would engage in enkoimesis; a sleep incubation, sometimes under the influence of hallucinogens, that was meant to aid in the healing process by mimicking death and resurrection through mystical communion with Asclepius. In the Roman period, it may have been converted into the archive of the Asclepieion.

On the east side of the altar is another temple, Temple C. Temple C was constructed during the Antonine dynasty but replaced an earlier temple that dated to the 3rd century BCE. The dedication of both phases of the temple is unknown, but it is generally believed they were probably dedicated to Apollo. Only the stylobate of the temple and foundations of the cella seem to remain, with several columns reconstructed with a few bits of original column. East of Temple C, some very fragmentary bits of Building E, sometimes referred to as the lesche, remain. This has been identified as a small stoa that seemed to house statuary, and during the Roman period, ex-votos collected at the sanctuary. On the east side of the staircase leading to the upper terrace was a large, niched exedra. This dates to the original phase of construction and seems to have been an assembly area for the priests operating here.

The monumental staircase between the middle and upper terraces is dated to the 2nd century BCE building phase. It really consists of two staircases as there is a small, intermediate terrace between the two. The upper terrace consists of a large, central temple that immediately at the top of the staircase (Temple A) and stoai that lined the east, west, and north sides of the terrace. A monumental propylon marked the entrance to the terrace, though nothing remains of this. The upper terrace was also the location of the sacred cypress grove; a few cypress trees are visible on the terrace as well as elsewhere on site.

Temple A was originally constructed of limestone in the 3rd century BCE phase of building and was dedicated to Asclepius. During the 2nd century BCE phase, the limestone temple was replaced by marble construction. The crepidoma as well as some elements of the lower few courses of the actual temple are preserved. Two halls were constructed flanking the entrance to the temple in the 2nd century BCE, but nothing is visible from these. The stoai surrounding the terrace seem to have originally been constructed of wood, but were also replaced by marble construction in the 2nd century BCE. Pretty significant elements of the foundations of the stoai remain, and their course and form are pretty easy to trace and visualize.

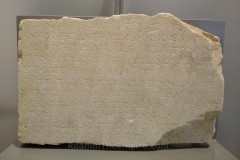

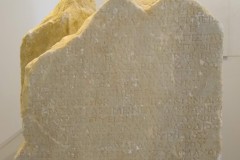

The last element of the sanctuary, back toward the beginning to the east of the lower terrace, is the lapidarium. A small building here preserves a number of inscriptions found at the site. Among the most notable are a letter from Nero to Kos that mentions Gaius Stertinius Xenophon dated to 54 CE and letters from various cities and rulers recognizing the asylia of the Asclepieion. Also among these inscriptions are records of victorious athletes of the Asclepieia Megala and inscriptions dedicated by cities honoring physicians from Kos who had served those cities.

In all, I spent about 2.5 hours at the Asclepieion, not counting the cat sanctuary in the parking lot. When I visited in 2021, admission was only 8 Euros, and that was a little bit hefty, but was still worthwhile and I had no problems with it. Since then it’s nearly double to 15 Euros, which is really pushing the envelope of what it is worth. It’s an interesting site and an important site, but really has no defining feature like a theater that seems to drive those kinds of mark ups for other sites (whether or not that is reasonable or not is a completely different discussion). As someone especially interested in archaeology, I would have begrudgingly paid 15 Euros (as I have done before) for my first time, though would have strongly reconsidered on a repeat visit. If I were just a tourist with a passing interest, however, I’d likely skip it altogether at that price point.

Sources:

Appian. Historia Romana, XII.4.23, XII.17.115-117.

Aristotle. Ton Peri Ta Zoia Historion, 5.19.

Arrian. Alexandrou Anabasis, 6.11.

Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae, 12.77, 13.71.69, 15.32, 15.38.

Demosthenes. Yper Tis Rodion Eleftherias, 27.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 5.54.3, 11.3.8, 14.84.3, 15.76.2, 16.7.3, 16.21.1, 19.68.3, 20.27.

Evagrius Scholasticus. Ekklisiastiki Istoria, 2.14.1.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Herodotus, Historiai, 1.144, 7.164.

Homer. Illiad, 2.2.677.

Hyginus. De Astronomia, 2.16.

Jerome of Stridon. Chronicon.

Livadiotti, Monica. Due edifice termali a Coo città: tipologie a confronto.

LIvadiotti, Monica. “The Infrastructure of a Hellenistic Town and Its Persistence in Imperial Period: The Case of Kos.” Thiasos, No. 7.2 (2018).

Ovid. Metamorphoses, 7.357.

Parker, Robert. “The Cult of Aphrodite Pandamos and Pontia on Cos.” Kykeon: Studies in Honour of H.S. Versnel. HFJ Hortsmanshoff, HW Singor, FT Van Straten, and JHM Strubbe (eds.), Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 3.23.6, 8.43.

Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis, 5.134, 11.26-27, 13.5, 14.10.1, 15.18.2, 20.100.1, 23.14.1, 27.27.1, 29.4, 35.79, 35.92, 35.161, 36.20

Polybius. Historiai, 30.7, 37.

Rocco, Giorgio and Monica Livadiotti. “The Agora of Kos: The Hellenistic and Roman Phases.” The Agora in the Mediterranean from Homeric to Roman Times: International Conference Kos, 14-17 April 2011. A. Giannikouri (ed.), Athens, 2011.

Scafuro, Adele C. “Koan Good Judgemanship: Working for the Gods in IG XII.4.1 132.” Greek Epigraphy and Religion: Papers in Memory of Sara B. Aleshire from the Second North American Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy. Emily Mackil and Nikolaos Papazakadas (eds.), Leiden:Brill, 2016.

Sherwin-White, Susan M. Ancient Cos: An Historical Study from the Dorian Settlement to the Imperial Period. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen, 1978.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographica, 12.8.6, 14.1.15, 14.2.19, 15.1.3.

Tacitus. Annals, 2.75, 4.14, 12.61.

Thucydides. Historiai, 8.41-45, 8.108.

Great article! I found the section on the healing rituals and the potential use of hallucinogens during enkoimesis particularly fascinating. It’s amazing how advanced ancient medical practices were. This reminded me of modern veterinary medicine. I was recently reading about a vaccine called Vectormune ND (https://pillintrip.com/medicine/vectormune-nd) used for poultry, which is a recombinant vaccine leveraging a viral vector – a concept that feels almost like a high-tech echo of ancient methods using biological agents for treatment. I’m curious, based on your research, do you know if there were any specific, known medicinal compounds or preparations from plants on Kos that were uniquely associated with the Asclepieion’s healing practices?

Thanks for reading! Interesting question, it’s not my field of expertise; I don’t think there are any known plants that are endemic specifically to Kos that would have been used in that capacity. I think most of those particular types of plants would be regionally available. While it’s hard to attribute things specifically for use in the Asclepieion, I did come across this study, and though the whole thing is paywalled, even the introduction and abstract offer some information about some of the medicinal properties of plants that would have been available on Kos in antiquity. Availability and medicinal use probably give us the best picture of what may have been used in the Asclepieion:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214786117305843

There’s also a corpus of early medical texts that are popularly attributed to Hippocrates that offer some clues as to what may have been used:

https://classics.mit.edu/Browse/browse-Hippocrates.html

And, of course, Pliny the Elder is also typically a great source for this kind of thing. This has a handy table of remedies organized by specific flora:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/60688/60688-h/60688-h.htm