Most Recent Visit: July 2024

The site of Colonia Flavia Scupinorum, often shortened to Scupi, is located on the north bank of the Axios (the modern Vardar), a few kilometers outside the modern capital of North Macedonia; Skopje. The immediate area of the settlement has produced archaeological evidence suggesting the location had been inhabited since at least the 12th century BCE. Starting in the late 6th century BCE, archaeological evidence of occupation in the direct vicinity of the later settlement becomes scarce. The surrounding environs were occupied by various ethnic groups including Illyrian, Thracian, and Paeonian, though none of them seemed to have settled the area. By the end of the 3rd century BCE, the Dardani had moved into the territory of the future settlement of Scupi.

The Dardani supported Rome against the Kingdom of Macedonia in the series of conflicts through the late 3rd and early 2nd century BCE. In 170 BCE, the Macedonians conquered the Dardani, but just a few years later when Macedonia become a protectorate of Rome following the Third Macedonian War, the Dardani were allowed to remain autonomous in reward for their support. By the early 1st century BCE, the Dardani were themselves in conflict with Rome and became the target of campaigns by Sulla in 85 BCE and Gaius Scribonius Curio, proconsul of Macedonia, from 75 BCE to 73 BCE. These seem to have been related to pacifying the area in advance of further conflict with Mithradates.

Marcus Antonius again led a campaign against the Dardani in 59 BCE, seeking to pacify the groups north of Macedonia and secure Roman access to the Danubius (modern Danube). Marcus Licinius Crasses finally conquered the Dardani in 29-28 BCE and their territory was incorporated into the Roman hegemony, though the Dardani would continue to resist Roman occupation. It seems that at this time a legionary camp may have been established in the neighborhood of Scupi.

Colonia Flavia Scupinorum was established during the reign of Domition with veterans from Legio IV Scythica, Legio V Alaudae, Legio V Macedonica, and Legio VII Claudia. Other names associated with the settlement were Colonia Flavia Felix Dardanorum and Colonia Flavia Aelia Scupi. In addition to Scupi, Flavia also appears to have been a shortened version of the name by which the city was called. Around this time, in 86 CE, the province of Moesia was divided into Moesia Superior and Moesia Inferior, with Scupi being included in the former. It seems to have been the administrative center of the district of Dardania within Moesia Superior. The city was apparently prosperous but unremarkable through the remainder of the 1st and through the 2nd century CE. Scupi was likely raided during the Costoboci invasion of Roman provinces in 170 CE. The city again suffered damage about 100 years later when the Goths and Heruli invaded Roman territory circa 268-296 CE.

Scupi found renewed importance following Diocletian’s administrative reforms in the early 4th century CE and entered into a new period of prosperity. Theodosius I visited Scupi twice in 379 CE and 388 CE. As the Roman border regions became less secure Scupi was repeatedly devastated by Goths, Ostrogoths, and Huns throughout the 5th century CE. The final death knell of the city came in 518 CE, when it was nearly completely destroyed by an earthquake and the remaining population shifted to a hill about 4 kilometers to the southeast, where a fortress was built and around which the city of Skopje would develop.

Getting There: Skopje is the capital of North Macedonia, and can be reached by train, bus, and plane from elsewhere in Europe. The main archaeological area is located in the northern extent of the city. Technically it can be reached by bus, but I found the bus system in Skopje to be confusing and somewhat unreliable. Bus times were not posted and even when consulting employees of the transport system, buses frequently did not arrive according to what I was told. The #21 bus does go from the train/bus station to the site, but again it seemed hit or miss actually catching it. Google Maps’ timetables are not reliable. Failing that, it’s about a 4.5 kilometer walk from the city center.

The Scupi Archaeological Area is located along Улица 10 (Street 10) at the northern extent of the city, just beyond the Vardar River. Opening hours are hard to pin down, as there doesn’t seem to be any official schedule. It was closed on the weekends when I visited in July, but seemed to be open weekdays from the morning through the early afternoon, though again there didn’t seem to be a set timetable. I actually showed up on a Saturday thinking it would be open, but was told by the business next door that it wasn’t open on Saturday but would be open on Monday. Admission is free.

Before reaching the archaeological site, there’s a road that runs along the east side of the archaeological area to the theater, which is not inside the archaeological park. Just inside the fence (but not really accessible within the site) are the remains of some of the eastern fortifications of the city. The stone fortifications were constructed shortly after the Costoboci attack in 170 CE. Previously the walls were likely earth and wood. The walls were again strengthened in the 5th century CE owing to increasing pressure from invading groups. Some adjacent extramural structures are also visible.

At the end of the road is the theater. The theater seems to have been constructed during the reign of Hadrian, perhaps coinciding with the emperor’s visit there sometimes between 121 and 125 CE. Significant remains of the theater have been uncovered and conserved, but unfortunately they are quite overgrown, at least in the summer. One can see the most robust elements of the theater, but the heavy overgrowth obscures not just the details, but prevents one from accessing perhaps some of the best viewpoints for the theater. The northern/western part of the scenae area has been mostly obliterated by the presence of a modern cemetery.

Continuing down the road another 400 meters is the main entrance to the site. There was no ticket window or entrance, though there was a building where some of the site archaeologists were working near the middle of the site. They spoke English and were quite happy to talk about the site. The site itself is mostly overgrown when I visited. I was told that the budget really only allows for one or two clearings a year, and that the growth is especially robust in the summer. As such, not much of the site was directly accessible. There were some paths cut in the brush to allow views over the areas, but I was told to keep strictly to those paths as snakes were an issue on site.

Upon entering the site, there’s part of an excavated insula immediately to the right. At left is a collection of inscriptions and architectural elements on display. The western part of this insula is occupied by a series of small, individual residential structures dated to the 6th and 7th century CE. These overlay early buildings of an undetermined function. The eastern side of the insula was dominated by a horreum built in the late 3rd century CE, constructed on the remains of earlier 2nd-3rd century CE buildings that were destroyed, likely in the Gothic/Heruli invasion circa 269 CE. The function of these buildings is unclear. The robust western wall of the horreum is fairly recognizable even among the overgrowth. Later in the 4th century CE, the southern part of the horreum was incorporated into a new bathing complex that functioned until the 6th century CE (probably abandoned after the earthquake of 518 CE), when it too was built over with small dwellings. The northern part of the horreum and later baths was replaced by a building with an apse in the 6th century CE. Though the exact function is undetermined, it is sometimes referred to as a basilica.

The western insula is bounded on the east by the cardo maximus. Only a few column bases are visible above the grass, though some paving stones from the street are visible when cleared. Across the road is another insula that is primarily occupied by a large bathing complex. This bathing complex was constructed in the 2nd century CE and functioned until the 5th century CE, with several periods of renovation and alteration. In the 6th century CE, a Christian basilica with an atrium was built over the caldarium in the southern part of the baths. Like the western insula, this area was mostly overgrown, though there were recent excavations in the eastern/southeastern quadrant of the baths that allowed very good visibility of this area, which was believed to be the cold water and auxiliary room section of the baths. There was even part of a wall with some intact fresco visible here.

The baths are bounded on the north by a decumanus, across which was an urban villa. The northern section of this villa was similarly excavated recently and so it was the other area of the site that was not really overgrown. The villa was constructed in the late 3rd century CE and seems to have been in use until the 5th century CE. The western portion of the villa was mostly devoted to a private bathing complex. To the north of the villa, and partially overlaying part of the villa, was an early Christian basilica with a baptistery. This was built in the late 5th century CE, overlaying a public building of some sort dating to the 4th century CE. The basilica functioned until the 6th century CE.

Given the state of the site, it was a fairly quick visit. It only took me about an hour, including a conversation with one of the archaeologists on site. There are a few helpful signs in Macedonian and English helping to explain the sites. The forum of Scupi was located a bit farther south; part of the civic basilica has been found, though it is on private land and is not accessible. About 500 meters northwest along Улица 10 are some remains of the northern necropolis just off the east side of the road. Also overgrown, but a few funerary stele and monuments are visible in the excavated area. A second necropolis to the south has also been identified across from the Hotel Evro Set, currently a construction area. The Skopje Aqueduct, located a couple kilometers from the archaeological site, is often referred to as Roman, but almost certainly dates to later than the 6th century CE, as the course of the aqueduct leads toward the fortress, rather than the site of ancient Scupi.

In Skopje, there are a couple museum spaces worth visiting. The first is the Archaeological Museum of the Republic of North Macedonia, located at Kej Dimitar Vlahov (Кеј Димитар Влахов), just east of the Stone Bridge. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10:00 to 18:00 and is closed on Mondays. Admission is 150 Macedonian Denars.

The north wing of the lower level is a space dedicated to statues, reliefs, and inscriptions dated to the Roman period from around North Macedonia, including Scupi. Highlights include the statue of a woman from Stobi and statues of Venus and Apollo from Scupi and Stobi, respectively. The south wing of the lower level was housing a temporary exhibition on the Heroic Age of Histria when I visited; mostly a collection of Iron Age grave goods from Histria. The upper level was predominately dedicated to the material culture of pre-Roman groups in North Macedonia, though there were early Christian objects in the north wing, including some terracotta icons dated to the 5th and 6th century CE and a presbyterium from the basilica at Suvodol, including mosaics. The highlight of the later collection is a significant portion of a 4th century CE glass cage cup from Taranes.

It took me about an hour and a half to go through the archaeological museum. There were lots of interesting objects, the vast majority being grave finds. It’s not an especially large museum but they certainly make use of the space they have. Most objects have information in Macedonian and English, though some of the more extensive informational signs were in Macedonian only (such as the information on the presbetyrium).

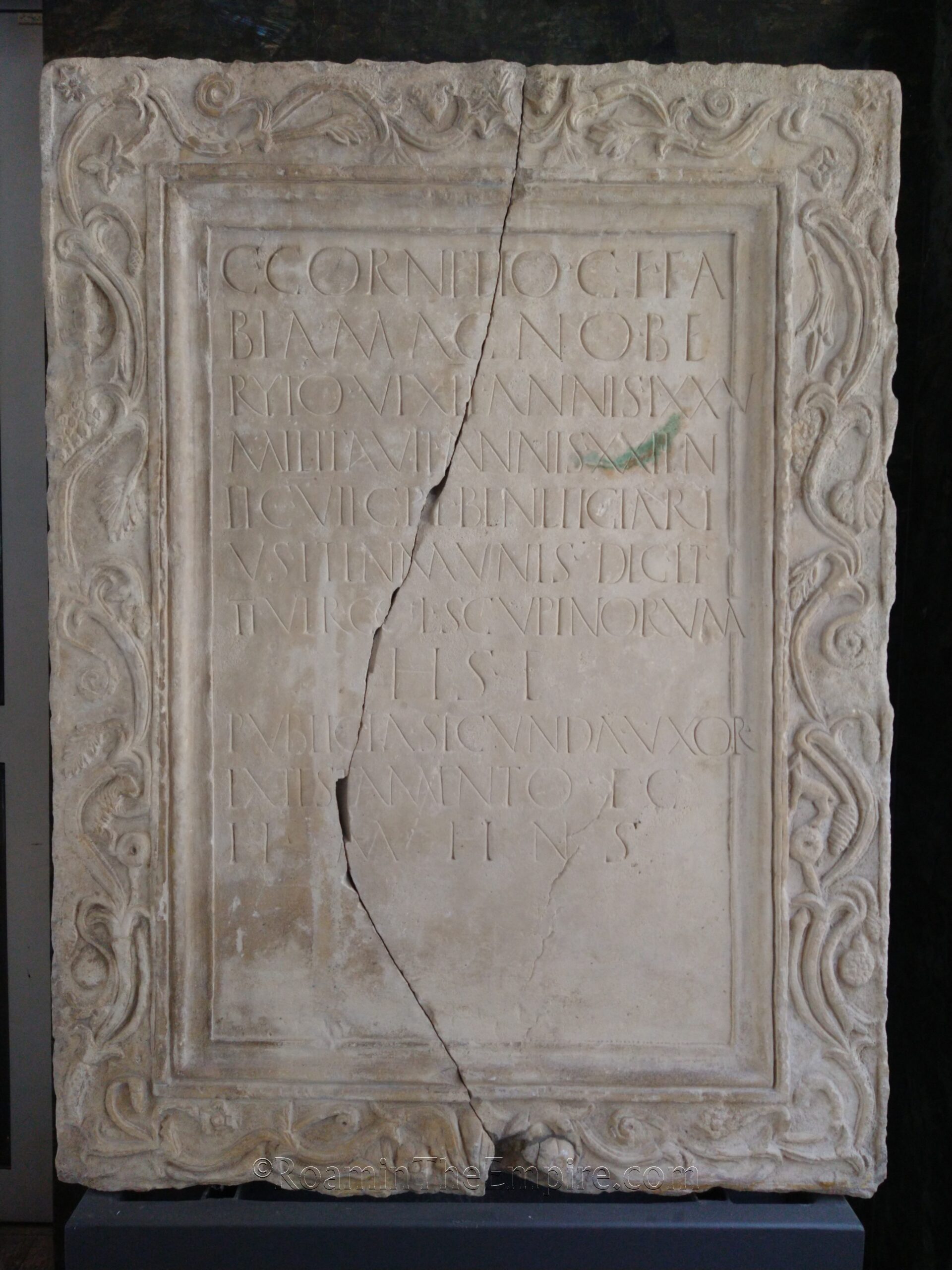

The second space is the Museum of the City of Skopje, located in the old railway station along Saints Cyril and Methodius street. This museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10:00 to 15:00 and admission is free. As the name suggests, it is sort of a general local history museum. One of the exhibit spaces includes some ancient objects. Chief among these is a statue of Venus Pudica that was found in the great baths at Scupi. Unfortunately the statue was encased in protective scaffolding when I visited. Also particularly interesting were three lead votives dedicated to the Danubian Rider. Out in front of the museum (always accessible) is a lapidary collection of mostly funerary inscriptions. The ancient part of the museum is quite small and can be visited in less than half an hour. Information was in Macedonian and some English.

With a well-planned itinerary (and no public transportation disasters), the site and both museums can certainly be done in a single day. It took me two days because of the incorrect assumption of the site being open on Saturday and plenty of public transportation mishaps. Neither of the museums had many other visitors and the site had none during my visit in July, so Scupi is certainly a bit off the beaten tourist path. The state of the site was a little disappointing, but it was also free and somewhat understandable. I was told the site was cleared that year in April/May, so that may be a more ideal time to visit to fully appreciate it.

Sources:

Hammond, N.G.L. and F. W. Walbank. A History of Macedonia Volume I: Historical Geography and Prehistory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Hammond, N.G.L. and F. W. Walbank. A History of Macedonia Volume III: 335-167 B.C. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Lenče, Jovanova. Scupi: Colonia Flavia Cupinorum Guide. Skopje: Museum of the City of Skopje, 2008.

Lenče, Jovanova. Scupi: Colonia Flavia Cupinorum. Skopje: Cultural Heritage Office, Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Macedonia, 2015.

Petković, Žarko. “The ‘Bellum Dardanicum’ and the Third Mithridatic War.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 63, No. 2 (2014), pp. 187-193.

Petrović, Vladimir P. “Pre-Roman and Roman Dardania Historical and Geographical Considerations.” Balcanica, No. XXXVII (2006), pp. 7-23.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.