Most Recent Visit: May 2021

In the lead up to the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, after wintering at Patrae and unsuccessfully attempting a move to Italy, Marcus Antonius moved his forces to the southern promontory at the mouth of the Ambracius Sinus (the modern Gulf of Ambracia), south of the town of Actium where a prominent temple to Apollo was located and where games were held in his honor. In preparation for battle, Octavian made his camp on the northern promontory. The battle occurred on September 2nd, 31 BCE, just outside the mouth of the Ambracius Sinus with Octavian (but really Marcus Agrippa) defeating Marcus Antonius and effectively turning the tide of the war in favor of Octavian. Two years later, in 29 BCE, at the site of his camp prior to the battle, Octavian erected a trophy on the hill and in the plain below it, a city dedicated to his victory; Nicopolis.

The name Nicopolis derives from the Greek goddess of victory, Nike, and the Greek term for a city, Polis. Literally Victory City. It was also sometimes called Actia Nicopolis, making reference to the older town across the strait from Nicopolis. In order to populate the town (presumably in addition to the colonization of veterans), Octavian had the inhabitants of nearby existing settlements such as Cassope, Orraon (Horreum), and Ambracia relocated to Nicopolis, leaving the original settlements largely abandoned. Like Patrae, Nicopolis was granted civitas liberta and was also civatas foederata. Octavian also re-instituted and reorganized the quinquennial Actian Games to be held at Nicopolis starting in 27 BCE which honored Apollo and commemorated the victory at Actium. As such, the games started on the day of the battle, September 2nd, and lasted for 4-5 days. At first they were administered by the Spartans, the only Greek city to support Octavian in the battle. Later on, though, the administration passed to Nicopolis. The games had previously been held as local games by the Acarnanians dating back to the classical period, and were also dedicated to Apollo.

Nicopolis quickly flourished with a port on either side of the peninsula and ample fish hatcheries. It was also an important point of contact between Greece and Italy. In 66 CE, Nero stopped in Nicopolis to participate in the Actian Games, winning a chariot race. When the philosopher Epictetus was exiled from Rome around 93 CE, as part of a general expulsion of philosophers from the city under Domitian, he took up residence in Nicopolis and established a school of philosophy there. He lived there until his death around 135 CE. When the province of Epirus was established under Trajan, Nicopolis became the capital. Both Trajan and his successor Hadrian were benefactors of the city, the latter of which visited the city in 128 CE and had a temple to Antinous built.

Nicopolis seems to have been largely spared in the Heruli invasions of 268 CE due to a reactionary reinforcement of the fortifications. During the reforms of Diocletian in the late 3rd century CE, Epirus was divided up into Epirus Vetus and Epirus Nova, with Nicopolis becoming the capital of the former. The Actian Games seem to have stopped in the mid-3rd century CE, before briefly being revived by Julian in the mid-4th century CE, who also made renovations to the city, which seems to have fallen into a state of neglect. About 375 CE, a major earthquake hit the region, resulting in significant damage to the city. Continued Gothic incursions led to the building of a new circuit of fortifications to enclose the now significantly smaller city sometime around the middle of the 5th century CE, perhaps during the reign of Zeno. They were then bolstered and repaired during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Justinian. Nicopolis seems to have largely fell out of use sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries CE as the population moved to the area of present day Preveza, a few kilometers to the south.

Getting There: The archaeological sites (and museum) of Nicopolis are in a mostly rural area. It’s relatively close to the city of Preveza (though not really within walking distance for most people), but even Preveza itself is a bit off the beaten path and not very easy to get to without a personal vehicle. The sites of Nicopolis are a bit spread out as well, so having a vehicle is advisable for visiting the remains of the city.

For the sake of creating a relatively linear itinerary, I’ll start with the southernmost of the points of interest, the Archaeological Museum of Nicopolis. As a matter of course, I usually save the museums for the afternoon when it’s less pleasant to be out at the sites. The museum is located on the National Road Preveza-Ioannina, a few kilometers outside the center of Preveza and a couple kilometers south of the core of the archaeological remains. In the summer (April through October) the museum is open Wednesday through Monday from 8:00 to 16:00 and is closed on Tuesday. The rest of the year it is open daily from 8:30 to 15:30. Admission is 8 Euros and includes entrance to the Archaeological Site of Nicopolis and the odeon.

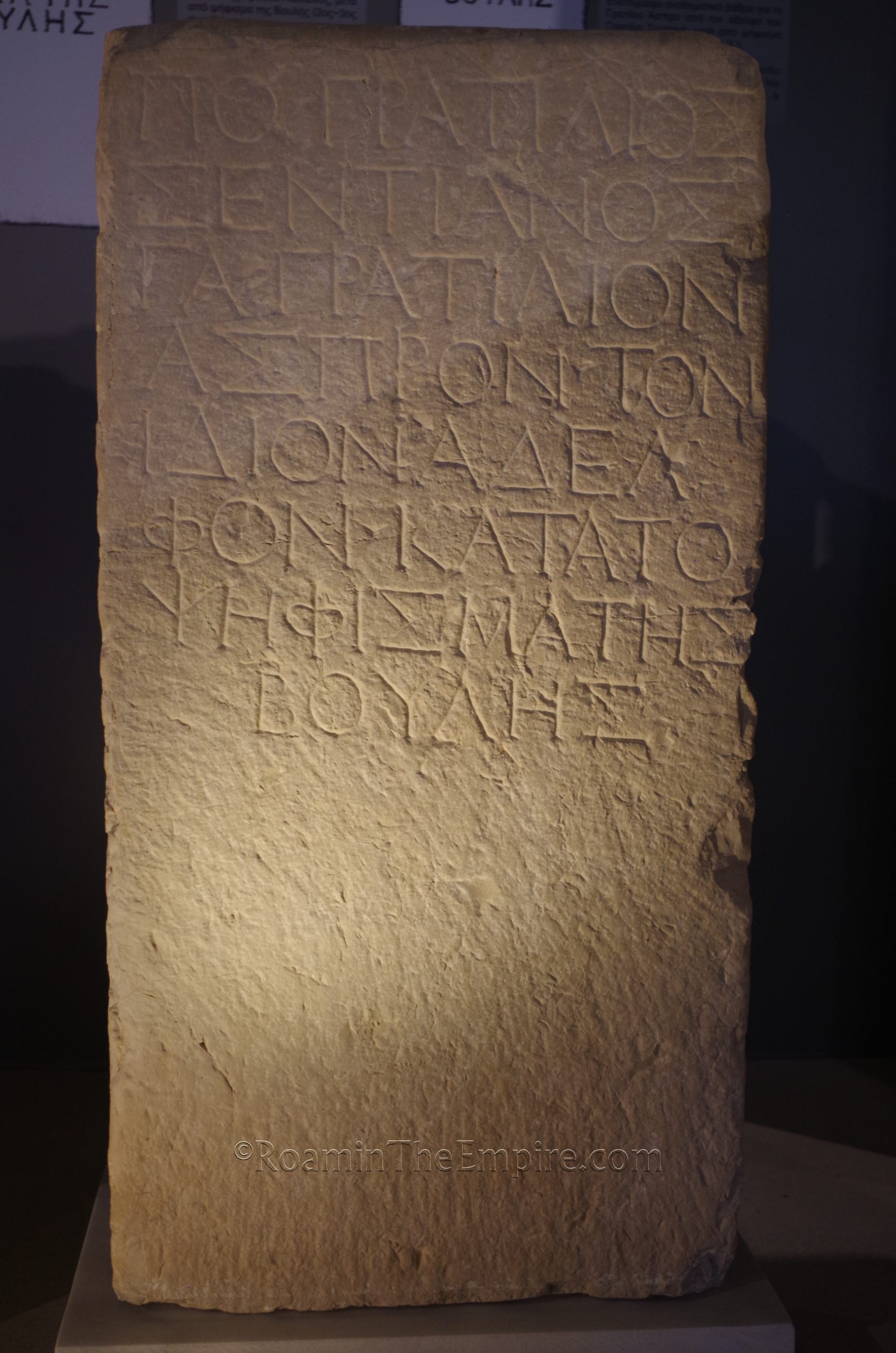

The museum has sort of a standard array of objects found locally among the remains of Nicopolis. One of the more interesting assemblages is that of remains from the victory monument of Octavian/Augustus. The collection also includes some well-presented and varied coins. There are a few nice statues and reliefs as well as an interesting marble base with ten of the Greek gods; some of them not the typical gods that one would expect depicted. There are some fragments of the tropaeum and other interesting objects such as coins and lamps associated with the Actian Games. Other than that, it’s actually a relatively small collection compared to the breadth of archaeological remains; it only took about an hour to go through. By no means is it inadequate, though. And this is perhaps due to the original archaeological collection of Nicopolis being destroyed in bombing during World War II. One aspect the museum does excel is the presentation and availability of information. There were many informational signs in English and Greek as well as a number of helpful maps and diagrams. As I noted before, I typically save museums for the heat of the day, but, given the context provided, it might not be the worst idea to see the museum before the archaeological sites.

Up the road (north) about 1.5 kilometers on the National Road Preveza-Ioannina is the southernmost remains of Nicopolis, the southern gate. The National Road essentially runs right through the entrance of the gate; the towers that flanked the entrance are preserved to a fairly significant height and can be seen on either side of the road. The Roman road exiting here lead to the southern harbor, in the present-day area of Margarona. This circuit of walls, the larger of two that encircled Nicopolis, was constructed in the years following the foundation of the city. A stretch of the walls leads eastward from the eastern tower of the gate and can be seen for about 70 meters in that direction.

The area to the south of this wall is fenced in and contains a number of pit graves and the foundations of a mausoleum associated with the southern necropolis that abutted the wall here. On the opposite side of the road, south of the western tower, a mausoleum and a few graves, as well as the remains of a sarcophagus, are also visible, but are not fenced in. There seem to be a few more funerary structures about 50 meters farther south, but this area is significantly overgrown and on private property, so I wasn’t able to investigate these.

The wall that leads east from the eastern tower eventually comes to the Church of Saint Stylianos, which doesn’t seem to be regularly open, but on the grounds of which are the remains of Basilica D. The Basilica is not visible from the small road that leads along the wall and the necropolis. Basilica D is dated to the first half of the 5th century CE.

Another 500 meters up the road, it intersects with the southeastern corner of the 5th and 6th century fortifications constructed following the contraction in the size of the city following the repeated incursions. The course of the walls have obviously been destroyed by the construction of the road, but significant portions are visible on either side. A small dirt road heads off to the northwest along which some remains of the wall can be seen. The foundations of a few towers right off the main road, as well as a pretty significant section of the wall a bit farther on. The area is pretty heavily overgrown, though, and as such these fragments of the walls aren’t especially visible. The road does continue along the course of the walls for about 185 meters before the walls veer off away from the road.

On the western side of the road, however, some much more significant and visible remains of the wall can be seen. This parallels a paved road with several areas where one can park as well. The first few towers and corresponding walls are only preserved to a height of about a meter or so, though after the third tower, the walls are preserved to a more significant height. The towers are still only preserved to about a meter or so. Interestingly, the shape of the towers alternates, with a round tower located at the corner near the main road, and then alternating between square, pentagonal, and semicircular shaped towers. Between the 5th and 6th towers, where the paved road (Epar. Od. Prevezas-Nikopolis) veers away from the walls, is the south gate of the settlement, also called the Fine Gate or Oraia Pyli. The arch of the gate is partially reconstructed. One can’t pass through the gate as it leads to a controlled archaeological area on the other side. A few faded informational signs are located at this point.

A dirt path continues past the gate along the exterior of the walls for another 250 meters or so along the perimeter of the walls before they turn northward. A pretty decent path continues along this western extent of the walls up the main gate, the Arapoporta, or also referred to as the west gate. Like the south gate, the Arapoporta has been significantly reconstructed. It also has a bit more monumentality than the south gate, being flanked by two reconstructed towers and having a much larger entrance. One of the towers can be entered via a doorway along the gate and niches inside the tower are visible. The walls continue to the north, but when I visited the path along the exterior was quite overgrown and made traversing the remaining 430 or so meters of the walls along the exterior nearly impossible. Growth along the path leading west from the gate also made getting wider views of the exterior of the walls difficult as well. A small informational sign is located right outside this gate.

Passing eastward through the gate to the interior of the wall circuit, however, allows for great views and the ability to walk the remainder of the western side of the fortifications until they more or less disappear at the point at which they would turn to the east to form the northern side of the settlement fortifications. There are some remaining fragments of the northern walls, but they’re very fragmentary and quite overgrown. Staircases leading to a somewhat preserved/reconstructed upper level above the gate entrance are visible, though the staircases are blocked off from use. Another, smaller gate, the Postern Gate, is located and visible about 175 meters north of the Araporta and is accessible from the interior.

Continued In Nicopolis, Epirus Part II

Sources:

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Kitzinger, Ernst. “Studies on Late Antique and Early Byzantine Floor Mosaics: I. Mosaics at Nikopolis.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Vol. 6 (1951), pp. 81 + 83-122.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 5.23.3, 7.18.8, 10.38.4

Pavlids, Evangelos A. Nicopolis: The Domus of the Ekdikos Georgios. Athens: Ministry of Culture & Sports, 2015.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographika, VIII.7.6.

Suetonius. Augustus, 18

Tacitus. Annals, 5.10.

Zachos, Konstantinos L. An Archaeological Guide to Nicopolis. Athens: Ministry of Culture & Sports, 2015.

Zachos, Konstantinos L and Maria Karampa. The Cemeteries of Nicopolis. Athens: Ministry of Culture & Sports, 2015.

Zachos, Konstantinos L., et al. The Odeum of Nicopolis. Athens: Ministry of Culture & Sports, 2015.