Most Recent Visit: June 2022

Little is known about the history of the Roman and pre-Roman settlement that preceded the Castrum Divionense; Divio (Modern Dijon, France). The name seems to derive from a word relating to a sacred fountain, which may have been present there. Evidence suggests habitation in the area from at least the Neolithic period onward, but the foundation date of Divio is unknown. The area and any pre-Roman settlements presumably came under the hegemony of Rome along with the rest of the area following Caesar’s conquest in the Gallic Wars around 50 BCE. Funerary finds suggest a fairly robust settlement in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, however no extensive remains from the core city from that period are present. It was located on the primary branch of the Via Agrippa between Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (modern Köln) and Lugdunum (modern Lyon), constructed in the late 1st century BCE. In the 3rd century CE, probably during the reign of Aurelian, a fortress was built here, Castrum Divionense. This was seemingly constructed on what would have been the core of the previous settlement of Divio.

Getting There: Dijon is a fairly large city, and as such it is well connected to most places in the region. For instance, there are pretty regular (once an hour on average, though sometimes slightly more or less frequently) direct trains between Paris Gare De Lyon and Dijon. The journey averages between 1.5 and 3 hours, depending on the train, and costs between 16 and 75 Euros, again depending on the train, with the average being about 40 Euros for the quicker off-peak trains.

As the historical synopsis for Divio/Castrum Dvionense suggests, the archaeological remains of the city and castrum are pretty limited. There is one place in the center of Dijon to see ancient remains; the Musée Rude. Located at 8 Rue Vaillant, the museum is open daily except for Tuesdays. In the summer, between June 1 and September 30, it is open from 10:00 to 18:30. The rest of the year the hours are 9:30 to 18:00. Admission is free.

The Musée Rude houses a collection of sculptures and casts of architectural elements by the 19th century artist François Rude. While some of these do have classical themes and are worth a look at, the collection is not exceedingly large. Tucked away in the back of this small museum set inside the apse of the former Eglise Saint-Etienne, are the remains of a small bit of the fortification wall that encircled the 3rd century CE castrum. While the course of the 1170 meters of fortification walls and 33 towers have been identified, it is only this small bit of the wall that is publicly visible. Even with the Rude collection, it’s no more than about a 10 minute stop unless you are particularly interested in the artist. Unfortunately there is no English information in this museum.

It is worth mentioning that there is also a bit of one of the towers preserved and incorporated into the buildings off Rue Charrue, about 350 meters southwest (as the crow flies). It would seemingly be visible from the courtyard at 15 Rue Charrue, however this is a private courtyard and does not have public access. Because of the height of the buildings, it is also not visible from the street.

Just down the street to the west, from the Musée Rude along Rue Vaillant (which then turns into Rue Rameau) is the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon at 1 Rue Rameau. Like the Musée Rude, this museum is also open daily except for Tuesdays and is open in the summer (same dates) from 10:00 to 18:30and the rest of the year from 9:30 to 18:00. Admission is free at this museum as well.

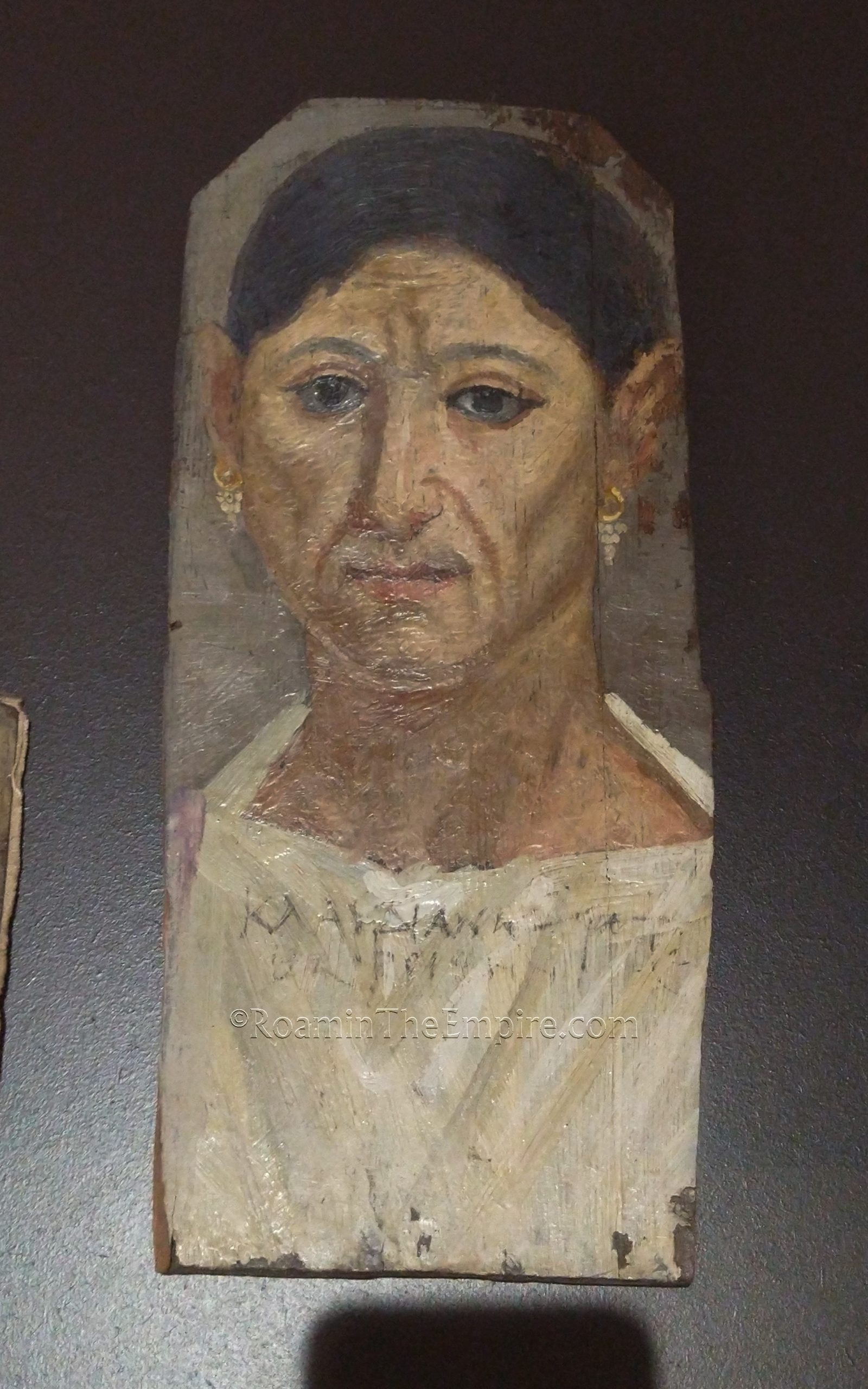

The collections of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon are primarily comprised of post-antiquity pieces. This includes a number of paintings depicting historical or mythological scenes from antiquity. There’s quite a large collection of 18th and 19th century reproductions of ancient portraits and sculptures as well as original neoclassical sculpture depicting figures and themes from antiquity. Also among the collections of the museum is a relatively modest spread of ancient artifacts. These are primarily Egyptian in origin, but also includes some Greek material as well. Included among the artifacts are a number of Fayum mummy portraits dating to the Roman period as well as a few painted mummy masks ranging in date from the Hellenistic period to late antiquity. In a separate space (up on the very top floor of the museum) are some Cycladic figurines and a random fragment of a Greek sculptural head. Like the Musée Rude, there is not much English information available in the museum. The titles of works are typically translated into English, but everything else is in French. The collection of ancient objects takes maybe 10 minutes or so, but I spent about 2 and a half hours total in the museum.

Farther west down the street, which continues on to Place de la Libération as Rue Rameau, and then Rue de la Liberté on the other side of Place de la Libération, and just past the plaza is a sign that delineates the extent of the Roman castrum. It’s just to the right of the large doorway Archives Municipales de Dijon (91 Rue de la Liberté). There’s nothing ancient actually visible here, just a sign that marks the western extent of the castrum.

About a 10 minute, 600 meter walk from the castrum sign, at 5 Rue Docteur Maret, is the final stop for ancient Castrum Divionense, the Musée Archéologique de Dijon. The museum is open in the summer (April 1 to October 31) daily except for Tuesdays, when it is closed. The hours are from 9:30 to 12:30 and 13:30 to 18:00. The rest of the year the museum is only open on Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday from 9:30 to 12:30 and 13:30 to 18:00. Admission is 6 Euros.

The collections of the archaeological museum are housed in the former abbey of the Cathédrale Saint-Bénigne de Dijon. The museum contains a pretty large assembly of artifacts collected not just in the local environs of Dijon, but also from the wider region. The upper most floor of the museum has a pretty wide variety of objects dating from the Paleolithic to the Merovingian period. A healthy amount of these do date to the Gallo-Roman period, though. Lots of small finds, but also a number of larger reliefs, inscriptions, and even some statuary. I thought the bronze statuettes here stood out in particular. There were some very nice glass pieces as well.

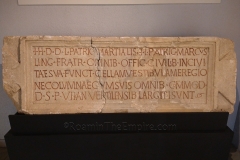

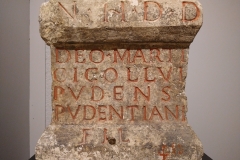

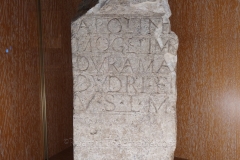

The middle level of the museum is largely religious art from the post-antique period. The bottom floor/basement level of the museum houses one of the most interesting objects in the museum, a 2nd-1st century BCE bronze figure of the personification of the Sequana (modern River Seine) riding on a boat with a duck figurehead. This was found at a sanctuary at the source of the river (about 45 minutes northwest of Dijon and can be visited, but not much ancient visible) and is on display with a number of other objects found at the sanctuary, including several wooden votive figurines dating to the 1st century CE. The bulk of this part of the museum, though, is taken up by the large lapidary collection that is primarily composed of funerary inscriptions and reliefs found locally around Dijon. There are also some votive reliefs and inscriptions among the artifacts in this area of the museum as well, and a few other non-funerary pieces.

The Musée Archéologique de Dijon was overall very good. Like the other museums in Dijon, though, there was pretty much nothing in English or any language other than French. It’s certainly not a problem, given that it is a French museum, but it’s worth knowing ahead of time, as it can significantly reduce the amount of time needed for a museum if one is unable to read any of the information presented (or is a non-native speaker that needs extra time to comprehend). I spent a total of about 2 hours in the museum. There was a lot to see, but not overwhelmingly so.

It is also worth mentioning that there is supposedly some foundation elements of the Via Agrippa preserved in the Parc de la Colombière, a couple kilometers to the southeast of the city center. The park is, unfortunately, about 650 meters by 520 meters in area with paths crisscrossing all over it. Given the size of the park, I was unable to find and confirm the existence of these elements.

The remains of Castrum Divionense and the relevant museums of Dijon are pretty easy to see within the confines or a single day. Given that the archaeological heritage of the Gallo-Roman period is extremely sparse and that the museums are large and interesting, but not overwhelming, it could probably even be done in a day trip from Paris or Lyon. Despite the dearth of archaeological remains, the archaeological museum, in particular, has some very good pieces that makes a stop in Dijon very much worth it.

Sources:

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.