Most Recent Visit: June 2018.

The modern city of Lyon lies at the confluence of the Saône (referred to as the Arar or Sauc-Onna in antiquity) and Rhône (Rhodanus, in antiquity) Rivers and is the third largest city in France behind Paris and Marseilles. In antiquity, the predecessor to Lyon, Lugdunum, was a similarly important city in Gaul, perhaps the most important, largely due to the geographic position at a major river confluence. Prior to the Roman foundation of the city, there was continuous Gallic occupation of the area by the Segusiavi (or Segobriges) since at least the 4th century BCE. Notably there seemed to be two settlements; on the Fourvière Hill (a name derived from ‘forum’ and where most of the extant Roman remains are located) to the west of the Saône and in the plain between the Saône and Rhône. The area or settlement are not mentioned specifically by Caesar, and information prior to the Roman foundation of the city is scant.

In 47 BCE, a Roman colony was established in the nearby Allobroges town of Vienna (modern Vienne), about 25 kilometers down the Rhône. Shortly thereafter, though, in the midst of the Post-Cesarean Civil War in 44 BCE, the Allobroges revolted and expelled the Roman colonists from Vienna. In 43 BCE, Lucius Munatius Plancus and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, were tasked with founding a new settlement for these refugees, choosing this site of the Fourvière Segusiavi settlement for Colonia Copia Felix Munatia, the original name of the Roman settlement. At some point prior to the Augustan reorganization of Gaul in 22 BCE, when the province of Gallia Lugdunensis was created, the city took the name of Lugdunum. This name is theorized to come from a reference to the Gallic god Lug or Lugus, who may have had a sanctuary on the Fourvière Hill, or possibly as a derivation of the Gallic word lugudunon, which means ‘fortress’. The reorganization placed Lugdunum as the capital of the province derived from its name, Gallia Lugdunensis.

Not only was Lugdunum the capital of the province, but it effectively became the capital city of the Three Gauls (Gallia Comita); Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Narbonensis, and Gallia Aquitania. Under the direction of Marcus Agrippa, a road network was constructed throughout Gaul, with Lugdunum becoming the hub of the network. In 12 BCE, Drusus dedicated an imperial cult altar to Roma and Augustus at the city (the Altar of the Three Gauls, which would feature on coinage struck there starting after the establishment of the Lugdunum mint in 15 BCE) with the names of the 60 Gallic tribes of the Three Gauls engraved, and marked the first of the annual Concilium Galliarum, in which the chieftains of the tribes would meet to elect a priest and hold games.

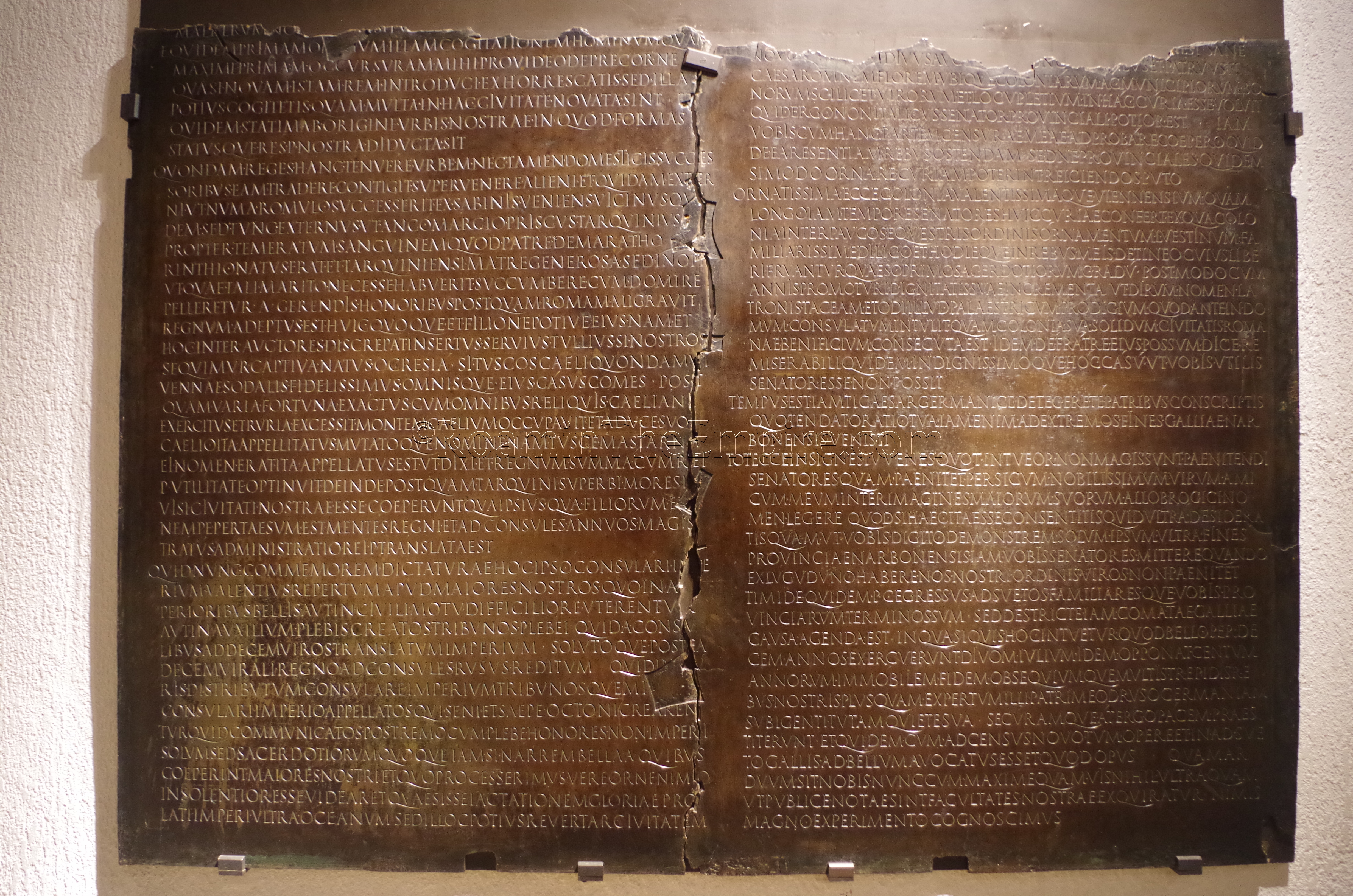

Throughout the early empire, Lugdunum became a frequent stop for the imperial family. Caligula visited the city near the end of his reign, and Suetonius tells of him selling the imperial property of his sisters there after exiling them. He also had Herod Antipas exiled to Lugdunum. Drusus resided in Lugdunum from 13 to 9 BCE, and his son and future emperor, Claudius, was born there in 10 BCE. Perhaps because of his birth there, Claudius seemed to have paid special attention to the city, stopping there on his way to and from Britain during his campaign there. In particular, he had a bridge over the Rhône built there and improved the road network between Lugdunum and Italy. In 48 CE, Claudius made a speech (a bronze transcription of which is on display in the museum in Lyon, and was found in the area of the Altar of the Three Gauls) before the Senate, at the request of the Gallic leaders, for allowing the inclusion of land owning Gallic citizens in the senatorial class. Claudius was ultimately successful in his request. At some point during his reign, the city was officially renamed Colonia Copia Claudia Augusta Lugdunenisium.

Nero also had somewhat of a relationship with the city. After the Great Fire in 64 CE, the citizens of Lugdunum contributed money toward the rebuilding in Rome, Nero returned the favor when a similar fire affected the city. This somewhat ingratiated the emperor to the city, and when in 68 CE, Gaius Julius Vindex, the proconsul of Gallia Lugdunensis, led a revolt against Nero to install Galba as emperor, the people of Lugdunum were largely resistant and refused to join in the revolt. This led to the city being briefly besieged by forces from nearby Vienna until Vindex was defeated a few weeks later. When Nero died and Galba became emperor for a short period of time, Lugdunum again did not support Galba, but instead threw their loyalty behind Vitellius, who arrived in Lugdunum and made his declaration as emperor there before heading to Italy where he defeated Otho, but was in turn defeated by Vespasian.

Lugdunum continued to prosper through the end of the 1st century CE and into the 2nd century CE and expanded from the hill down into the river valley. The confluence of the rivers and being the hub of the road network inevitably lead to it being the economic center of the whole of Gaul. The city seemed to flourish especially during the reign of Hadrian, and at its pinnacle may have had a population as high as 200,000. In 188 CE, the future emperor Caracalla was born there. Following the assassination of Commodus in late 192 CE and Pertinax in 193 CE, a war of succession between 4 imperial candidates played out over the course of 193-94 CE. Among the two vying for power were Septimius Severus and Clodius Albinus, who concluded an unofficial agreement to share power in order to defeat the other two, Didius Julianus and Pescennius Niger. Septimius Severus successfully defeated the other two, and Albinus effectively retained control of the empire in Gaul, Britain, and Hispania. By 196 CE, though, Albinus realized his position was tenuous, at best, and mobilized his legions in revolt against Severus. Albinus made Lugdunum his headquarters, and on February 19, 197 CE, a massive pitched battle between Albinus and Severus took place, involving between 150,000 and 300,000 troops between the sides, depending on interpretation of the sources. The evenly matched forces apparently fought for two straight days before the battle finally turned in Severus’ favor, and resulted in Albinus either committing suicide in Lugdunum or being executed.

The battle apparently had a long lasting effects for Lugdunum, as the city never seems to have completely recovered from the destruction and/or plunder it incurred during and after the battle, and entered into a period of decline. By the time of Diocletian, other cities in Gaul had eclipsed Lugdunum in importance, and administrative reforms were carried out from that time that reduced Lugdunum to the administrative capital of a much smaller region. The shift of the empire eastward further exacerbated the decline within the Roman Empire, and in the 5th century CE it was incorporated into the Burgundian kingdom, where it once again retained some importance.

Getting There: Being the third largest city in France, Lyon is pretty easily accessible from most places in France via train (as well as directly by train from Geneva), and from further abroad by the nearby Lyon-Saint Exupéry Airport. Buses are also a cheaper but, typically, much slower option. To give some idea, the trip from Paris to Lyon, via train, runs about 2 hours and costs between 25 and 100 Euros. With the huge variation in fares for French trains, it’s a good idea to plan ahead with schedules on the SNCF website. Once in Lyon, there are bus, tram, and metro options throughout the city for getting around.

Perhaps the best place to start is the Musée Gallo-Romain de Lyon-Fourvière, the archaeological museum devoted to the Gallic and Roman objects excavated in the city and surrounding communities. It is located adjacent to the theater/odeon complex at 17 Rue Cleberg. The museum is open Tuesday to Friday from 11:00 to 18:00 and on Saturday and Sunday from 10:00 to 18:00. The museum is closed on Mondays. Entrance to the museum is 7 Euros when there is a temporary exhibition, and 4 Euros when there is not.

The Musée Gallo-Romain de Lyon-Fourvière is, without a doubt, impressive. It is certainly the most impressive museum I saw during my time in France, and ranks among one of the best museums I’ve seen in all my travels. Though the museum was opened over 40 years ago, it has a sleek, modern feel and presentation. It is also deceptively large, with the exposed building making up just a small part of it; most of the museum is underground, set inside the hill the museum rests on. This led me to make a critical error in judging the amount of time I needed to see the museum when I visited.

The collection here is no less than amazing. It is extraordinary not only in its size, but also in the quality of the artifacts. There are numerous figural mosaics that are presented in an interesting and effective way. Some are optionally viewed through viewing areas in the floor on the level above them, so one can get a direct view down on them, which makes for a great viewing position. They can also be viewed up close at ground level. One mosaic that is particular interesting is that of a chariot racing scene with depictions of two chariot wrecks.

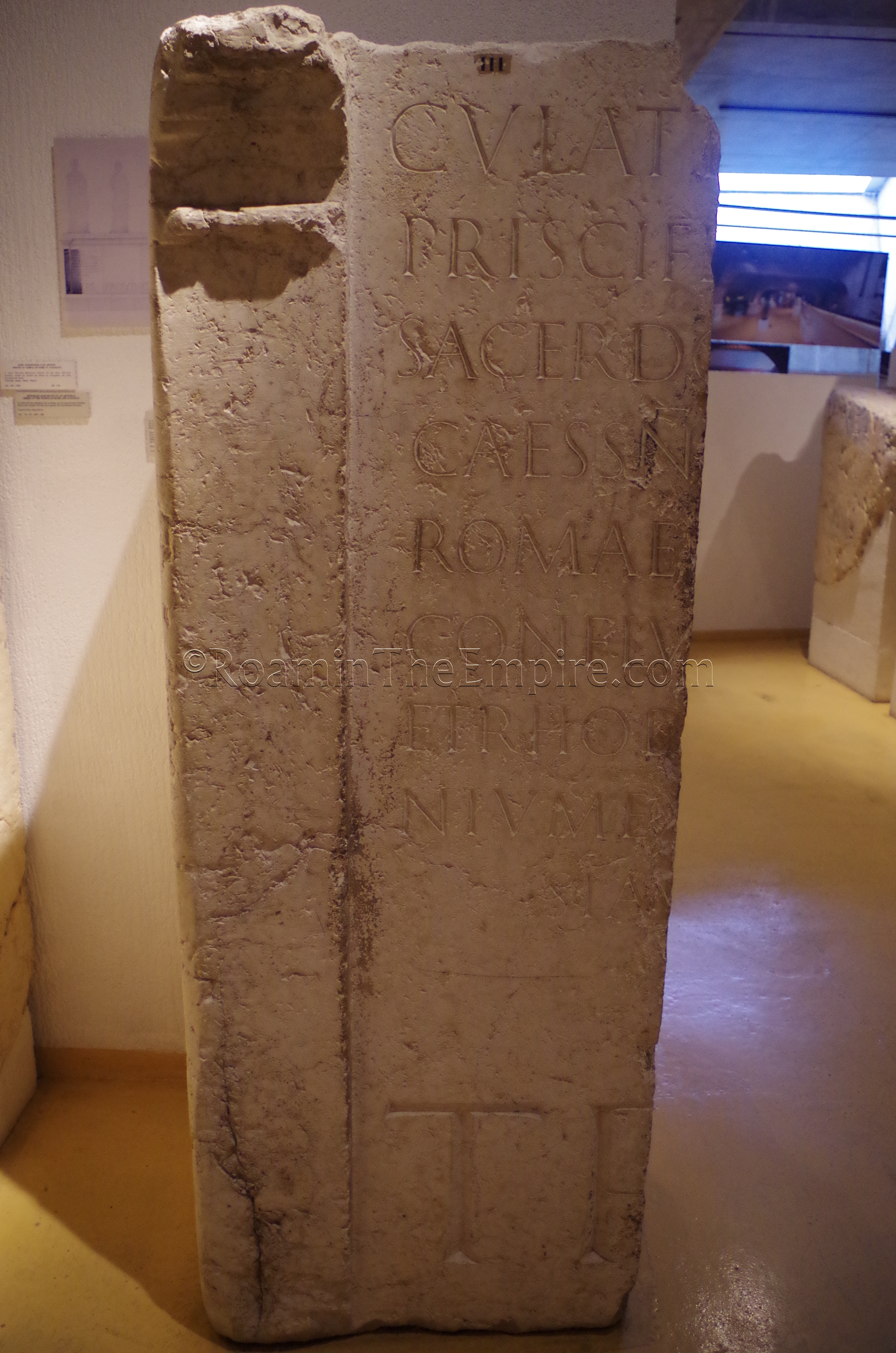

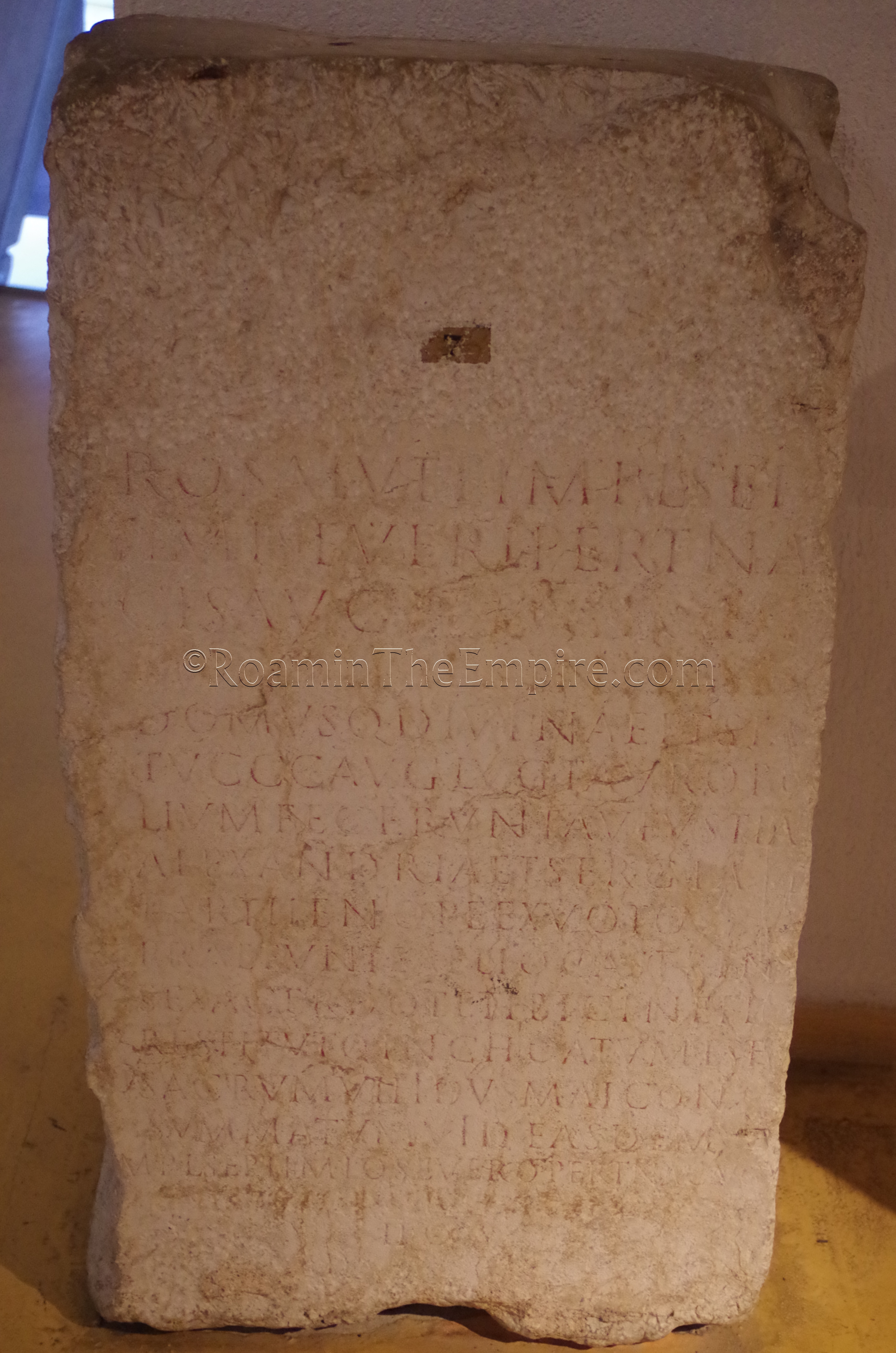

There are monumental inscriptions, including the dedicatory inscription from the amphitheater and the names of the Gallic chieftains from the podium of the amphitheater. There are a number of the large honorific inscriptions from the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls. Other highlights of the collection include the previously mentioned bronze tablet of Claudius’ speech before senate, fragments of a bronze Gallic lunar calendar, and a lead sarcophagus decorated with scenes of chariot racing. There are a number of interesting inscriptions, particularly some of the funerary inscriptions, of which there were quite a few (even before having to rush through part of them). This is certainly not a museum that gets bogged down in displaying tons of small, repetitive objects. Though there are plenty on display, they are displayed in an interesting and meaningful way.

The museum is absolutely ‘must-see’ and I really can’t say enough good things about it. I spent over 2 hours in the museum, but, because a good deal of it is built underground, I severely underestimated how much time I needed and easily could have spent another hour or more inside. I have honestly run into a lot of rude museum personnel, but, that was not the case here. Usually, when it comes to closing time, I’m always quickly hurried out, even at the half hour warning. Here, the docent/guard actually stopped me when I started to head out with about 20 minutes still left, as he could see I clearly wasn’t finished, and instead invited me to keep browsing a little longer until he had to herd me back to the entrance. Lots of informational signs with translations in English, as well. There’s really no reason not to visit the museum.

Continued in Lugdunum Part II.

Sources:

Audin, Amable. “Cybèle à Lugdunum.” Latomus, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1976, pp. 55-70.

Cassius Dio, Historia Romana, 54.32, 75.3, 76.6.

Drinkwater, J.F. “Lugdunum: ‘Natural Capital’ of Gaul?” Britannia, Vol. 6, 1975, pp. 133-140.

Fishwick, Duncan. “The Dedication of the ‘Ara Trium Galliarum.’” Latomus, Vol. 55, No. 1, 1996, pp. 87-100.

Fishwick, Duncan. “The Temple of the Three Gauls.” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 62, 1972, pp. 46-52.

Graham, A.J. “The Numbers at Lugdunum.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1978, pp. 625-630.

King, Anthony. Roman Gaul and Germany. University of California Press, 1990.

Livy, Periochae, 139.

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historiae, 4.31.

Pseudo-Plutarch, De Fluviorum et Montium Nominibus, VI.

Scullard, Howard Hayes. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome From 133 B.C. to A.D. 68. Menthuen, 1966.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo, Geographica, 1.1, 1.11.

Suetonius, Life of Caligula, 17, 39.

Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 2.

Tacitus, Annals, 1.51 1.65, 3.41.