Most Recent Visit: June 2022

The ancient settlement of Colonia Augusta Ruaricorum was located on the southern banks of the Rhenus (modern Rhine River) at the site of modern-day Augst, Switzerland. The modern name of the city is derived from the ancient name, which was initially shortened to Augusta and then to Augst. Pliny the Elder (and later authors echoing him), mention the source of the Danubius (Danube) being close to the city. The identified source of the Danube is about 75 kilometers away to the northeast. The exact origins of the ancient city are somewhat unclear. A Colonia Raurica was originally established around 44 BCE by Lucius Munatius Plancus (per a funerary inscription on his tomb at Getae, a copy of which is on display at the museum lapidarium), one of Caesar’s legates in the Gallic Wars and proconsul of Gaul at the time, in the relatively newly conquered territory of the Raurici, who would lend their name to that of the colony. The Raurici had been part of the migrations with the Helvetii in 58 BCE that had precipitated Caesar’s intervention in Gaul. The chief settlement of the Raurici was effectively at the site of modern Basel.

The supplanting of the colony was part of a series of measures taken to protect the newly acquired territory from incursions across the Rhenus from the east. No evidence of occupation prior to 15 BCE has been found at the site identified as Augusta Ruaruicorum, though, leading to some speculation that the original colony bearing the Rauricorum name was not located here, but rather farther west in the area of modern Basel, where the Raurici settelement was located. This colony may have been destroyed or abandoned in the turmoil of the civil wars that followed shortly thereafter, necessitating an eventual re-founding. It is also possible that after the establishment of the colony by Plancus, it was only done so ‘on paper’ so to speak, and that the colony was never actually constructed, again due to the interventions of the civil wars, In this case, it was not until after things had settled down that the colony was actually laid down here and re-founded with the Augustan name.

In any case, it was in 15 BCE, with the campaigns of Drusus and Tiberius to pacify populations in the Alps, that an important military presence was established the area and it seems this is when the previous colony gained was re-founded with the name Augusta, or when a second colony was founded as Colonia Augusta Rauricorum at the place that is now come to be identified with the settlement. The colony symbolically and practically consolidated the border regions of both the recently pacified Alpine groups and again, the eastern frontier of the province. One inscription attests to a much longer name that may have been used which attests to the original founder; Colonia Paterna Munatia Felix Apollinaris Augusta Emerita Raurica.

Augusta Rauricorum underwent a major revitalization and renovation around the middle of the 1st century CE. Legio I Adiutrix and Legio VII Gemina Felix were stationed here during the campaigns of Gaius Pinarius Clemens in 73-74 CE. As the border regions in the area became more stable, however, the city took on a less military and more commercial function through the late 1st and through the 2nd century CE. An earthquake around 250 CE and Alemanni incursion shortly after in 260 CE combined to largely destroy the city. A fortification, the Castrum Rauracense, was built around 300 CE, as the area was once again at the forefront of the frontier. This fortification was constructed north of the original settlement, much closer to the banks of the river. A small settlement still existed, but not on the scale of the previous occupation. The fort too was destroyed by Germanic invasions around 351 CE, and most Roman troops were withdrawn from the area around 400 CE.

Getting There: Augst and neighboring municipality Kaiseraugst (surprisingly not derived from the ancient title, but rather the inclusion of the latter but not the former in an imperial Hapsburg territory) are not especially large population centers, but they are quite close to Basel, the third largest city in Switzerland behind Zürich and Geneva. As such, there is pretty regular commuter rail service between the two; typically at least three departures an hour during the day. The journey is only ten minutes and it costs 3.80 CHF each way. The exact schedules can be found here. Taking a private vehicle, parking is fairly easy. There are three lots specifically for visitors to the ancient city, though two of the three are paid. Parkplatz 2 at Giebenacherstrasse 31, however, is free, and is pretty centrally located; it is marked in red on the map. Most of the core sites can be visited on foot, aside from a few outlying villas and remains of the aqueduct in the area.

The remains of Augusta Rauricorum are kind of a hodgepodge of open access and entranced sites, which makes a nice little, logical loop a bit difficult depending on when one starts out. When I visited, I did a lot of backtracking in order to try and fit everything in, so I’ve tried to shift things around a little bit in an attempt to make it a little more logical. Where I started, and where I’m starting things for this rundown, is at the amphitheater. The closest parking to the amphitheater is Parkplatz 3 (which is really only a couple minute walk south from Parkplatz 2). From there, there’s a path (Wallstrasse) that heads west parallel to the A3 highway. There are a number of informational signs along the path. These signs are predominately in French and German, though there are a couple with a little bit of English. One talks about remains of a wall and gate across the highway. While these aren’t visible, the outline of the wall, gate, and road leading from the gate can be seen in some satellite images. The path then cuts to the north to the amphitheater.

The amphitheater is open access, and there is no temporal restriction on visiting or ticketing. The monument here was constructed around 170 CE. A natural depression in the landscape allowed for the cavea to be mostly supported by the natural sloping of the depression, with just the upper ring and the entrance ends that spanned the valley needing free-standing support. The amphitheater replaced a previous building on the spot and seems to have been constructed with financial support from local benefactors. Capacity is estimated to have been about 13,000 spectators. By 280 CE, the amphitheater fell out of use and was largely dismantled to provide building material for the new fortifications constructed in the wake of the 260 CE sack of the city.

Most of the interior podium wall of the amphitheater has been preserved or (mostly) reconstructed, though pretty much nothing remains of the seating. A trio of rooms that led off the arena floor are also present and visible, one of them enclosed and seemingly being used as a maintenance storage. The most robust remaining part of the amphitheater are the walls on the south side flanking what would have been the porta sanavivaria of the amphitheater. Some significant portions of these walls remain or have been reconstructed. There are a couple signs on this end of the amphitheater, primarily in French and German, but with some English.

A path leads away from the amphitheater to the west, and then intersects with a small road, the Templehofweg. Heading north on this road, about 215 meters, is the Heiligtum Grienmatt, or the Grienmatt sanctuary. The foundations of the primary building of the sanctuary are preserved here. It seems to have been primarily dedicated to Asclepius and Apollo, but also to Sucellus, Hercules, and the gods associated with the days of the week. In particular, there seems to have been a healing spa associated with the sanctuary, though the remains are no longer visible. A portico, of which there are currently no visible traces, would have also enclosed this temple. Much of the sanctuary was robbed out for building materials. Usually the temple is open access, but unfortunately, when I visited, work was being done for restoration of the temple, and the path that leads around it was inaccessible and any access to the rear part of the monument was blocked off. Much of the front was also obscured by work related materials as well. There was an informational sign for the temple in French and German, but no English.

Right before the temple, Templehofweg turns into Schulstrasse, which can be followed further north before it curves to the east and intersects with Giebenacherstrasse. There are a few minor sites to the north that may be worth a look. Right near the intersection into Hauptstrasse, on the southwest corner of the intersection, just before the bridge over the Ergolz River, is a mosaic. The geometric mosaic is displayed on the side of the building with small informational sign. Just on the other side of the bridge, on the same south side of the street, is a rather worn Corinthian capital on display. There is a rather lengthy description of the capital and its history in French and German. It is believed to have been from a temple.

Just across the street (on the north side) is a small road that leads down under the train tracks and to the river. It looks like the road is private at first, but, it is indeed public access. A little ways to the west down this path along the riverside, are the remains of a well. It has pretty obviously been conserved and probably rebuilt to some degree, but it apparently originally dates to the Roman period. I’ve been unable to find any specific information about it, but it does seem to conform to other more securely dated Gallo-Roman wells I’d seen in the region.

Heading back south down Giebenacherstrasse leads to the core of the remains from the ancient city as well as the museum. The Museum and Römerhaus Augusta Raurica is located at Giebenacherstrasse 17. It is open daily from 10:00 to 17:00, with no scheduled weekly closing. Admission is 8 CHF.

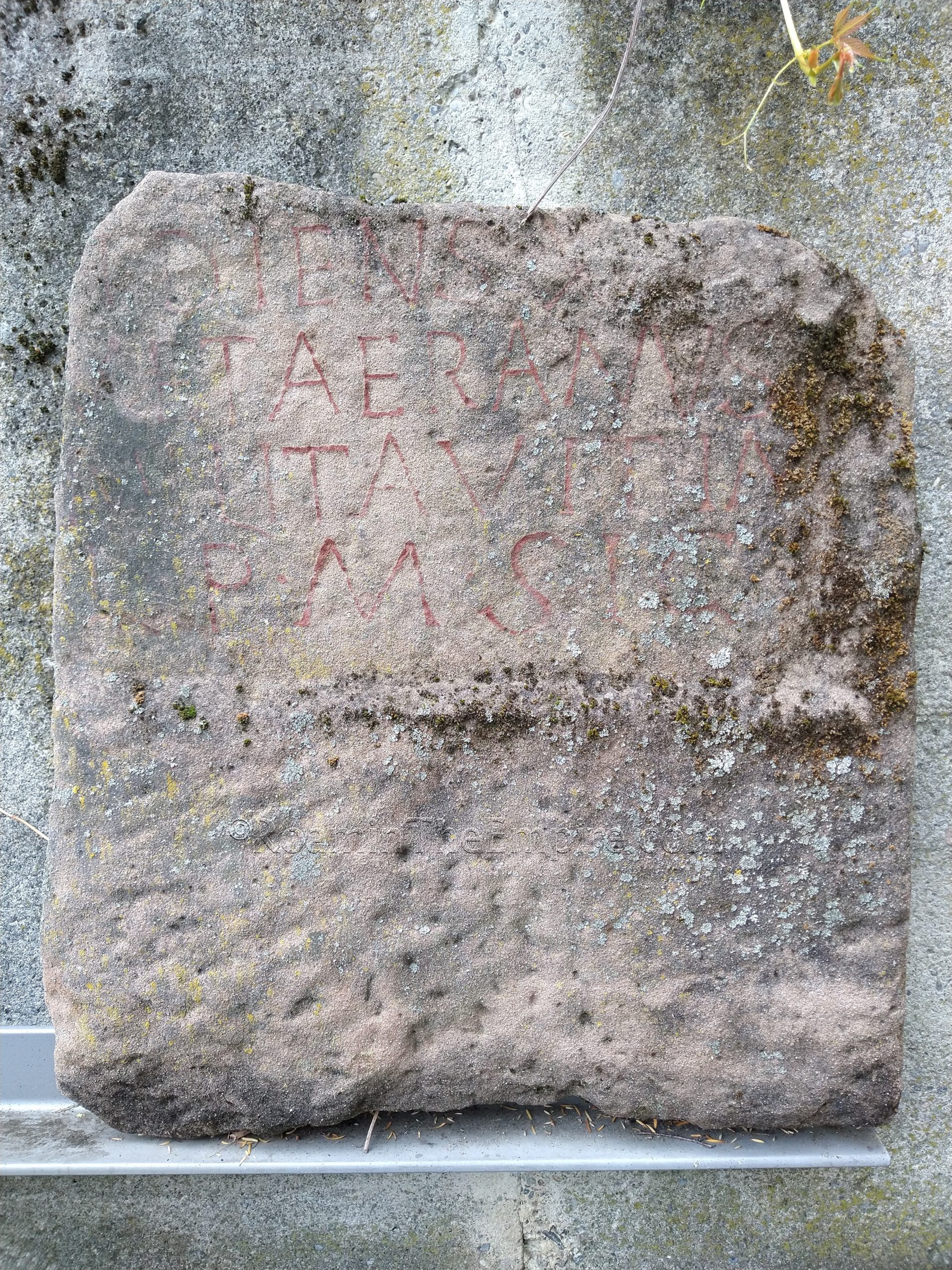

The museum is basically divided into three parts; the outdoor lapidarium, the Roman house reconstruction, and a small museum. The outdoor lapidarium is actually accessible at any time, it is not really in an enclosed area in which access can be limited outside the museum hours. That being said, there is hardly any information for the pieces in the collection. There is, however, a guide in English (and presumably a number of other languages) that can be temporarily loaned out to visitors from the ticket office. I get the impression it doesn’t get requested much, because the cashier was a little confused by my asking for it, but was more than happy to let me use while visiting the courtyard. There’s a typical array of pieces one might expect; dedications to gods, dedications to emperors, funerary inscriptions, and decorated architectural elements. A few of these are not original, but most are.

The bulk of the indoor area of the museum is taken up by the reconstruction of the Roman house. While it is nice for what it is, everything in it is a reconstruction; there are almost no original objects in that part of the museum complex. It’s pretty standard, and I certainly understand the reasoning for having it, the reconstructions seem to be quite a popular didactic tool in this part of Europe. Given how much space is devoted to the reconstruction compared to the display of actual objects recovered from the city, though, I can’t help but feel a little disappointed. The actual museum space of the complex is less than half, perhaps as little as a third, of the space; just a single room.

That single room of original artifacts, however, is remarkably well done. The museum essentially displays some selections from the discovery of a single 270 piece silver hoard found in the 1960’s. The cache of objects was found near the fourth century fortifications and the objects themselves date to the 4th century as well; believing to have been deposited around the middle of the century, at the time of the Alemanni attack. In addition to nearly 200 well-preserved coins, it also includes dishes and silverware; about 58 kilograms in all. Highlights include the so-called Constans platter, which is inscribed at the center and memorializes the 10th anniversary of Constans’ rule, a platter decorated with scenes from the life of Achilles prior to the Trojan War (signed by the creator, Pausylypos), and a plate incised with a port town scene at the center and hunting scenes around the edges. A lot is packed into the space, but, it certainly makes one want to see the other objects that have been discovered in the city but are not on display. Most signs in the museum have French, English, and German descriptions.

Continued In Augusta Rauricorum Part II

Sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus. Rerum Gestarum, 14.10, 20.10.13, 22.8.44.

Caesar, Julius. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 1.29, 1.5, 6.25.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Hufschmid, Thomas. Theatres and Amphitheatres in Augusta Raurica, Augst, Switzerland. Roman Amphitheatres and Spectacula: a 21st-Cemberury Perspective. Papers from an international conference held at Chester, 16th-18th February, 2007. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2009.

Pfäffli, Barbara. A Short Guide to Augusta Raurica. Augusta Raurica, 2010.

Pliny the Elder. Historiae Naturalis, 4.24.4, 4.31.2.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.