Most Recent Visit: June 2021

The Greek settlement of Chalcis (also Chalkis or Χαλκίς in Greek) is located about midway up the western coast of the island of Euboea (modern Evia), at the narrowest point of the Euripus, the body of water that separates Euboea from mainland Greece. The name is alternatively attributed to either the nymph Chalkida or possibly a derivation of the word for copper, chalkos (χαλκός), of which there were significant deposits in the area. Chalcis was reputedly founded with an Ionic colony prior to the Trojan War by Pandorus, son of the legendary Athenian king Erechtheus. Following the Trojan War, a second Ionic colony was established there by Cothus. Archaeological evidence supports habitation back to at least the Mycenaean era, and habitation in the wider area of Chalcis dating back at least 7,000 years.

Chalcis was an important metalworking and trade hub and was famous for the drastic tides caused by the shallow and narrow strait on which it sat. A swirling vortex created by these tides was said to be caused by Poseidon and nymph Arethousa. The city is first briefly mentioned in the Illiad in the roll of poleis contributing ships to the expedition. In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, Chalcis was particularly active in colonization, founding cities as far afield as Sicily and the Northern Aegean; the Chalkidiki peninsula owes its name to the plethora of cities there founded by Chalcis. It was apparently Chalcis that settled the earliest Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, Pithikousa and Cumae. Despite joint colonization ventures, during the same period Chalcis and neighboring Eretria were frequently at odds over the farmland in the Plain of Lelantum that lay between the two cities, sometimes drawing other regional powers into the conflict. This led to the Lelantine War of about 710 to 650 BCE, of which it seems Chalcis was the victor, but had negative economic consequences for both cities.

Following the Athenian expulsion of the Peisistratidae in the late 6th century BCE, Chalcis joined with other Boetian cities to make war on Athens. This resulted in a significant defeat of Chalcis and the division of the land of the noble class of Chalcis, the Hippobotae, among Athenian clernchs. Following the Persian invasion of Greece, the clernchs left Chalcis, but the city remained effectively under Athenian hegemony. The Chalcideans are noted as contributing a number of sailors for Athenian ships in the battles against the Persians and were part of the Delian League. In 445 BCE, Chalcis joined the Euboean revolt against the Athenians, which was quickly quashed by Pericles. The Hippobotae were completely expelled from the city this time, though. Another revolt occurs in 411 BCE, and it is at this point that the Chalcideans, in concert with the Boetians, construct a causeway to bridge the Euripus, leaving a channel just wide enough for a single ship to sail through, which is then spanned by a wooden bridge.

Though mostly independent, Chalcis was likely allied with Sparta from that point, and over the next 40 years or so retained nominal independence, but entered into various alliances, confederations, and coalitions alternatively with Sparta, Athens, and Thebes. Around 371 BCE, Chalcis comes under Boetian hegemony. Internal struggles on Euboea stoked by the Thebans and Athenians eventually led to the intervention of Philip of Macedon and another period of nominal independence for Chalcis. Chalcis initially allied with Macedon around 346 BCE, but then concluded an alliance with Athens a few years later. Fighting with the other Greek states at the Battle of Chaironeia in 338 BCE, the loss resulted in Chalcis coming under Macedonian hegemony. In 322 BCE, Aristotle fled from Athens to Chalcis and would die there the same year.

In 207 BCE, during the Roman campaigns against Philip V of Macedon in the Second Punic War/First Macedonian War, Chalcis was unsuccessfully attacked by Roman forces under Publius Sulpicius Galba. Just a few years later during the Second Macedonian War in 200 BCE, the Romans once again attacked Chalcis, this time under Gaius Claudius Centho, and were successful, inflicting heavy losses on the city. But lacking the forces to hold the city, the Romans withdrew. At the conclusion of that war, Macedonia lost possession of its territory in Greece, including Chalcis. Though the former Macedonian possessions in Greece were declared by the Romans to be free in 197 BCE, the Romans retained a garrison at a number of cities, including Chalcis. A few years later, in 192 BCE, the effectively neutral Chalcis was captured by the Seleucid-allied Aetolian League, helping to spark the Roman-Seleucid War that same year. Chalcis then aligned itself with the Antiochus III and served as a base for Antiochus III’s campaigns in Greece before he was driven out shortly after. When relations between the Achaean League and Rome spiraled into warfare in 146 BCE, Chalcis supported the Achaean League, which earned the city a sack and significant destruction as punishment when the Romans came out victorious. This also mostly ended the illusion of Greek independence, with Chalcis and the rest of Greece becoming more ensconced in Roman hegemony.

During the First Mithridatic War in 87 BCE, Chalcis aligned itself with the Mithridates VI and served as a base of operations in Greece for the Pontic general Archelaus, who was twice forced to retreat to Chalcis after suffering defeats against Sulla before withdrawing completely at the conclusion of the war in 85 BCE. In 27 BCE, Chalcis was organized as part of the Roman province of Achaea. Chalcis enjoyed relative stability and prosperity until the 3rd century CE, when it was subject, along with the rest of Greece, to a number of invasions by various Germanic groups resulting in destructions and economic decline. Chalcis was apparently restored under the reign of Julian, who is also noted as having constructed a new bridge across the Euripus. Occupation continued at Chalcis through the end of antiquity.

Getting There: Chalcis (or Chalkida/Χαλκίδα) is the primary city on Evia, and as such it is actually reachable by train from Athens. Trains leave Athens about once every two hours between 4:00 and 24:00 (presently at about 24 to 27 past the odd hour) and take an hour and twenty minutes to reach Chalcis. Current schedules should be available on this page. The Chalcis train station is actually on the mainland, right before the bridge, but that’s even only about a half an hour, 2.4 kilometer walk to the archaeological museum. Buses run from Athens to Chalcis as well through KTEL (with the bus station being literally next to the archaeological museum) but have found it to be an exercise in futility trying to find any kind of reliable schedule. If wanting to take a long haul bus in Greece, I’ve found the most effective method to be just visiting the actual bus station; the KTEL Evias bus station is at Str. Dagkli 41 in the northern part of Athens.

Despite the importance of the ancient city, the continued importance and habitation at Chalcis has led to very little of the ancient city remaining visible. What is there, as well as the new archaeological museum, is located at the southeastern edge of the modern city. That’s probably the easiest place to start. The New Archaeological Museum of Chalkis “Arethousa” is located at Arethousis 146, in the industrial building formerly housing the Arethousa bottled water factory. The museum is open Wednesday through Monday from 8:30 to 15:30 and is closed on Tuesdays. Entrance is 6 Euros.

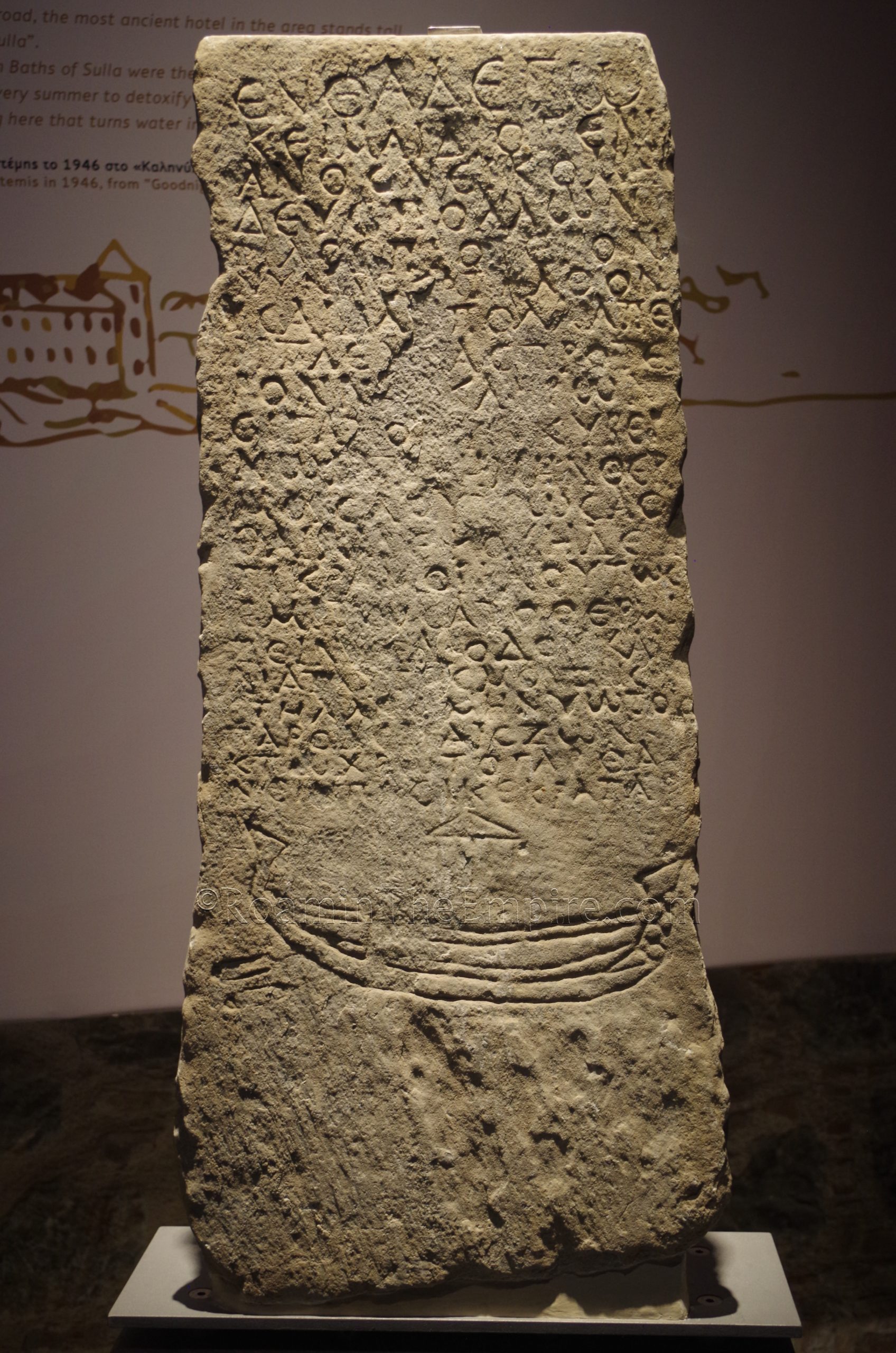

As the name suggests, the archaeological museum here is fairly new. It had actually just opened about 2 weeks prior to my visit, replacing an earlier archaeological museum in the center of the city. The collection is not incredibly large but has a very modern presentation. It hosts objects not just from Chalcis, but from the wider area of Euboaea/Evia, acting as sort of the regional museum for the island. What it lacks in volume it makes up for in quality. There are some nice fragments of statues, a mosaic, and various inscriptions. There are also some nice terracottas and coins on display.

The main part of the collection spans from about the 8th century BCE through to the Roman period. There are some earlier and much later objects on display as well. There was also a section dedicated to the history of the building. Most of the information in the museum was presented in both English and Greek with helpful illustrations and a lot of thematic information as well as about the objects themselves. There was a particularly interesting section on the transmission of the Euboean Greek alphabet and its influence on the development of the Etruscan and Latin alphabets transmitted through the colonies of Chalcis and Eretria in Southern Italy. In total it took me around 2 hours to visit the museum.

Just across the roundabout on which the archaeological museum is located, at Stiron 1, is the KTEL Evvoias station. There aren’t any real hours posted for the building, but it has a café and a the bus ticketing office and waiting room, so, it seems as though it is pretty much open for daylight hours. In the very center of the building, which is accessible through public areas, is an open courtyard in which some ancient remains are on display. These are identified as belonging to the ancient agora of the Chalcis, possibly an area associated with metalworking. The remains may date to the Classical period, and damage may be related to the Roman destruction of the city in 146 BCE. Unfortunately there is no information on site and information is very sparse elsewhere as well. Things were a little overgrown, there’s obviously a bit of neglect going on here, but given that one has to really dig to even figure out this is here, that isn’t entirely surprising.

On the south side of the roundabout is the source of the Arethousa Spring. There isn’t a whole lot to see here, it’s basically just a pond. A channel passes under the street to the west and it meanders around a park area behind the museum before flowing into the Euripus Strait. Not to be confused with the nymph Arethousa and the eponymous spring located at Syracuse, this one was named after the daughter of Hyperes, who was changed into the fountain after coupling with her grandfather Poseidon. The spring was an important source of water for the city in antiquity. The spring is just in an open area, and there’s no restriction of access to view it.

Doubling back to the museum and continuing on northwest on Arethousis for about 650 meters and 10 minutes walking are the remains of a bathing complex at Arethousis 116. Unfortunately, these do not seem to have any opening hours. They are sometimes claimed to be open access, but I went by a few times during my time and the gate was never open. Some stuff can be seen from outside the fence, including some remains of the hypocaust system of one of the heated rooms. There are a few mosaics toward the back of the site, including one depicting boxers, but, these are only vaguely visible, and the designs not distinguishable from the street at all. The baths date from between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. There is, fortunately, an informational sign (located within the site, but visible from outside) in English and Greek here.

The final, possible point of antiquity in Chalcis are the so-called Kamares, quite literally the arches. Heading back to the roundabout near the museum, the street that heads north is Stiron. About 450 meters north on this road, the arches of an aqueduct bridge cross over the road; traffic splits to travel through four of these arches. This roughly 65 meter stretch of aqueduct bridge (made up of 11 complete arches and a few partials) is often claimed to be of Roman origin. While the course of the aqueduct and perhaps some of the foundations possibly date to the Roman period, and there is a healthy mix of ancient materials that appear to be reused in the aqueduct, the majority of the structure of this remaining bit of the aqueduct seems to be of a much later construction, perhaps Venetian or Ottoman.

While the museum of Chalcis is very good, the archaeological heritage of the city is, unfortunately, otherwise mostly an afterthought and suffers from some degree of neglect. With a couple hours at the museum, everything else (including the later aqueduct) can be easily seen in about an hour. And even then, one thing is not really visible, another is neglected, and the third site is not even ancient. The museum is a worthwhile stop, but everything else might be largely disappointing to all but the most ardent archaeological enthusiasts.

Sources:

Appian. Historia Romana, 9.8.1, 11.3.16, 11.4.20, 12.5.31-34, 12.6.42-45, 12.7.50.

Bradeen, Donald William. A History of Chalkis to 338 B.C. 1947. University of Cincinnati PhD Dissertation.

Cassius Dio. Historia Romana, 18.15-16, 19.19.

Cicero. De Natura Deorum, 3.24.

Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca Historica, 10.24, 12.53-54, 13.44.2, 19-20.

Diogenes Laertius. Vitae Philosophorum, 4.54, 5.5-6, 5.10.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Heracleides Criticus. Bios Ellados, 26-30.

Livy. Ab Urbe Condita, 8.22.6, 27.30, 28.5-8, 31.22-25, 32.16, 32.37, 33-37, 42-45.

Lucan. Pharsalia, 5.270.

Herodotus. Histories, 5.74-99, 6.100-118, 8.1, 8.44-46, 8.127, 9.28.

Homer. Illiad, 2.535.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 1.38.1.

Plutarch. Philopoemen, 17.1.

Plutarch. Sulla, 19.4, 20.2.

Plutarch. Titus Flaminius, 10.1, 12.2, 16.1-3.

Polybius. Historiai, 5.2. 18.11, 18.45, 20.3-8, 38.3.3m 39.6.3.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo. Geographica, 1.3.16, 9.2.18, 10.1.11-13.

Thucydides. Histories, 1.15, 5.80, 6.3-4, 6.44-84.