Most Recent Visit: May 2021

Located about 8 kilometers away from the ancient city of Epidaurus, is the Sanctuary of Asclepius. Though administered by the Epidaurans, the sanctuary is a distinctly different entity than the city, but is often the sanctuary and not the city that is intended when many refer to ancient Epidaurus. A cult devoted to either a deity or a hero named Malos or Maleatas seems to have existed in this location dating back to at least the beginning of the Archaic period, perhaps even earlier. Malos may have been the king of Epidauros, Malas/Malos, who according to the Epidauran tradition of Asclepius had a granddaughter named Koronis. Koronis was impregnated by Apollo, with the resulting child being Asclepius. Koronis then left Asclepius exposed on the slopes of Mount Titthion, in the area of Epidaurus, where he was eventually found and nursed back to health. This also explaining the presence of his cult here.

Evidence of a sanctuary dedicated to Malos has been found on the slope of Mount Kynortion, roughly between the present location of the theater and the top of the ridge above the theater. One of the central features of this cult were rites associated with agricultural regeneration and renewal, which may have given way to the area’s link to healing. The nature of those rites and their association with other oracular sites also linked the sanctuary of Malos/Maleatas with an oracle.

These elements eventually seem to resulted in the conflation of Apollo and Maleatas as the epithet Apollo Maleatas, to whom a sanctuary was dedicated atop the ridge of the theater. By the late 6th century BCE, the healing cult of Apollo’s son, Asclepius, had been established here. Various myths attribute the maternal parentage of Asclepius to either Coronis or Arisone, and thus the subsequent birthing location and origin of the cult of Asclepius to either Epidaurus or Messenia, respectively. Pausanias recounts that the Pythian oracle at Delphi was posed the question of which location could lay claim to the origin of the cult of Asclepius, and ruled in favor of Epidaurus as the most ancient site of his worship.

Through the 5th century BCE, the cult at Epidaurus became quite popular. The Panhellenic Asklepia games were held at the sanctuary on a 4 year cycle; first being held as athletic contests, but by the end of the 5th century BCE also including poetry and music. Asclepius saw a general swell of popularity in Greece in the 4th century BCE, but particularly at the sanctuary where a large building program was undertaken.

In 293 BCE, a great plague in Rome prompted the consultation of the Sibylline Books, which in turn stated the necessity of the importation of Asclepius to Rome. A Roman delegation was sent to the Epidaurus sanctuary in order to retrieve a statue of Asclepius and bring him to Rome. During the rites, a serpent slithered from the sanctuary onto one of the Roman ships and hid. Seeing the snake, a creature associated with Asclepius as an auspicious portend, the Roman delegation set out to return to Rome. Upon arriving and sailing up the Tiber, the snake leapt from the ship and onto Tiber Island, marking the spot where a temple would be built to the god, and upon its completion, the ending of the plague.

After destroying Corinth in 146 BCE, the Roman general Lucius Mummius left a pair of dedications at the sanctuary following a visit there. With Roman hegemony solidly established in Greece, the sanctuary continued to function. In 87 BCE, Sulla looted the sanctuary of Asclepius in order to raise funds to support his campaign against Mithradates, and just a short time later in 67 BCE, the sanctuary was raided by pirates. Another major building program was undertaken in the 2nd century CE, with the specific benefaction of the senator Sextus Julius Major in 163 CE being a primary contribution to this. The sanctuary was once again raided in 395 CE, this time by Alaric the Goth. It seemed to function in its original capacity until about the mid-5th century CE, when Christianity put an end to the pagan rites. The site remained a center for healing even in the early Christian period, though, as a Christian basilica was constructed at the sanctuary in the late 4th century CE.

Getting There: Despite the fact that the sanctuary is kind of in the middle of nowhere, it is apparently possible to get there by public transport. Buses run from Athens to Epidaurus a couple times, but, like many of the other public transport options in Greece, the information is kind of spotty and frequently changes. The Epidaurus sanctuary is a rather popular destination, though, so there are quite a few companies in Athens, as well as some in Napflio and Corinth that run excursions to the site, though those often come with rather short times on site. As such, again, the best way to visit is with a personal vehicle. From Corinth, the trip is a little over an hour, and from Athens, about 2 hours. The site is pretty well signed once you get in the vicinity. From Corinth, it’s pretty much a straight shot down the old Isthmus to Ancient Epidaurus highway along the Saronic Gulf. There is ample parking at the site.

The Archaeological Site of Epidaurus doesn’t really have an address, as it’s sort of just off by itself outside of a town, at the terminus of a highway that essentially runs right to the site. Again, it’s pretty well signed once you get in the region and hard to not find. The site is open daily in the winter (November through March) from 8:00 to 17:00. In the summer months, the opening time is always 8:00, but there is a tiered closing time. In April, it is 19:00, from May through August it is 20:00. It then draws down by half an hour in half month increments over the next two months. The price of admission changes depending on the season as well; in the winter it is 6 Euros, and in the summer 12 Euros. Admission to the archaeological site includes the on-site museum.

Right near the entrance, and perhaps purposefully so, is the most famous monument of the sanctuary, the theater. This was first on my itinerary as I was, I think, the first person in the site that day. Despite arriving about a half an hour after opening time. As luck would have it, I had a full 20 minutes or so with the theater completely to myself before any other visitors showed up. Getting there first thing is definitely the way to go if you want to avoid crowds, though the lighting leaves something to be desired as there are still morning shadows causing a lot of contrast between parts of the theater.

The theater was constructed as part of the building boom at the sanctuary in the 4th century BCE. It was constructed as a venue for hosting the music and drama contests in connection with the games of the Asklepia. The capacity of the theater was around 12,000 spectators. According to Pausanias, the theater was designed by the architect Polykleitos the Younger, son of the famed sculptor Polykleitos. He was a sculptor in his own right as well, but was much better known for his architectural pursuits. The theater underwent some renovation in the 2nd century BCE; mostly the construction of a new stage area. Interestingly, after the site passed into the administration of the Romans, the theater did undergo the usual remodeling into the Roman theater form, but rather was left in its original Greek layout.

The theater is in a pretty good state of preservation. The proscenium was apparently at one time reconstructed, but it has since been removed, with the original state of the structure when uncovered now visible. Much of the theater is open access. There are a few sections of the cavea that are a little worse for wear and as such have been roped off to limit access to those areas, but overall, most of the theater can be explored. Various interventions have occurred over the years, but everything is pretty well done and nothing really looks unnaturally modern or out of places. The theater still serves as a venue for theater in the summers. I was there pretty early in the season, and there were no modern constructions put up for this purpose. I’m not completely sure if anything obstructive is used; video I’ve seen from events here doesn’t seem to show the same kind of obtrusive constructions that one sees at a lot of ancient venues repurposed for modern performances. But, the theater of the Epidaurus Festival later in the summer may indeed limit some access to the theater at times.

Adjacent to the theater is the Archaeological Museum of the Asklepeion at Epidaurus. I actually skipped seeing the museum right after the theater, as I wanted to use the cooler morning hours exploring the site, and rather saved the museum for the afternoon. But, for the sake of an organized itinerary through the site, it is best situated after the theater, as one needs to pass directly by the museum when going to the rest of the site. The museum is within the archaeological park, so there’s no separate entry; it is included in the ticket and has the same hours as the site.

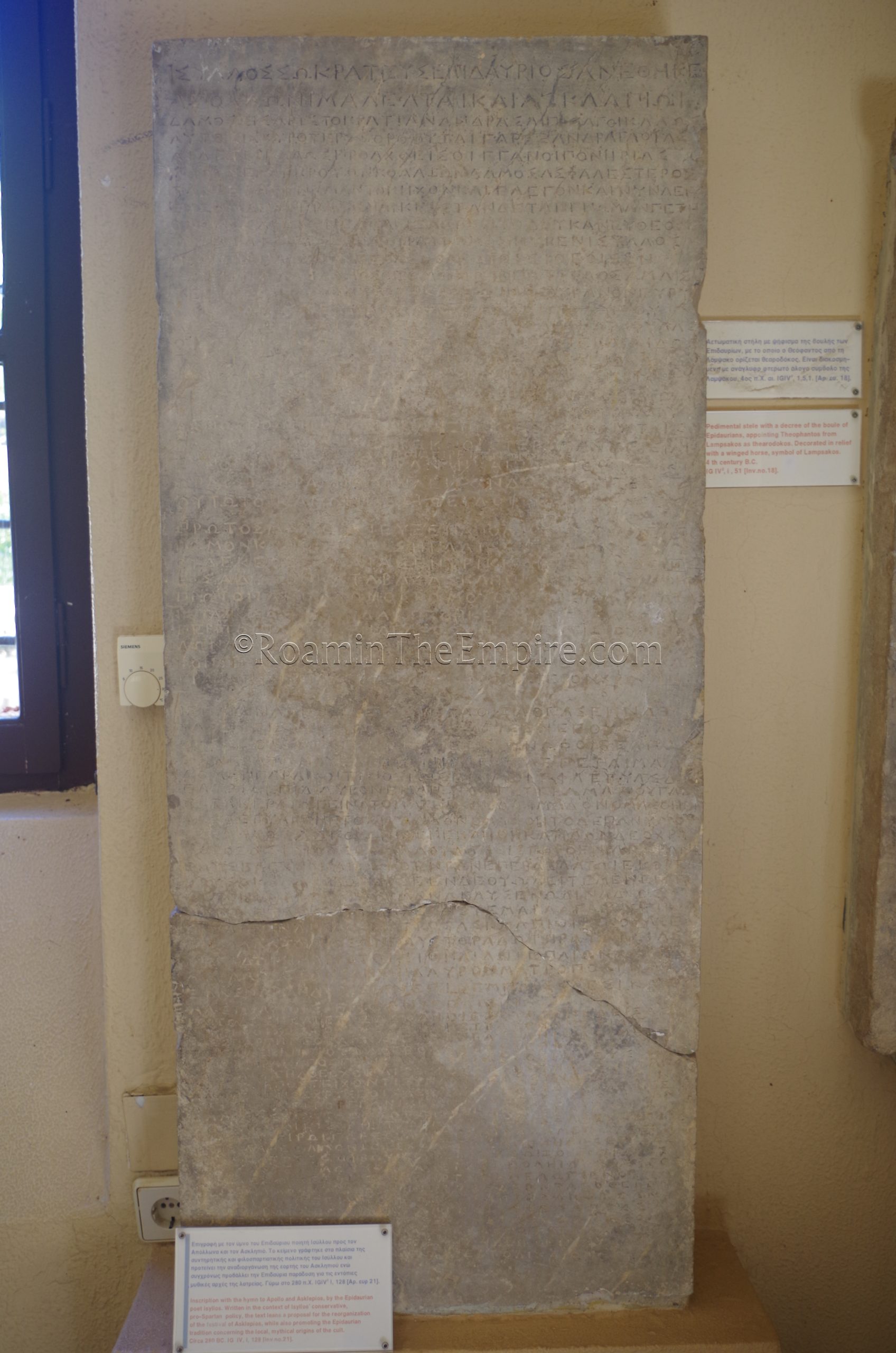

As one might expect, the archaeological museum contains finds from the surrounding archaeological area. The first room contains a number of inscriptions related to the healing sanctuary. Some of them are quite lengthy and are given in thanks to Asclepius for the healing of various maladies. Others generally attest to the god’s miraculous cures. Some construction related inscriptions also detail some of the building program of the 4th century BCE that was undertaken at the temple. The next room displays a number of statues and fragments of statues found at various locations. Some of them are reproductions of finds from the site that are presently located elsewhere. There are also a number of votive and honorary bases displayed here, but there is unfortunately no detailed information about the inscriptions present.

The final couple rooms are largely dedicated to architectural elements from various structures including the temples of Asclepius and Artemis as well as the Propylaia and Tholos. Again, some of these elements presented are actually plaster casts of the original architectural pieces. Outside the museum along the southern porch are a number of large stone artifacts including stele, inscriptions, and statuary fragments. There’s absolutely no information about any of them, unfortunately, though some are quite interesting. It’s not an especially large museum, all told, including a quick stroll along the outdoor elements, it only took about half an hour to forty minutes to see it all. Most objects with information cards and informational panels have descriptions in both English and Greek.

Heading to the north/northwest of the museum are the remains of a large structure known as the Katagogion. This square building served as a guesthouse for pilgrims and the ill who had come to the sanctuary to venerate or seek healing at the sanctuary. It seems to be outside of the actual sanctuary and had no religious significance, but was merely a practicality for those visiting the sanctuary. It was built in the late 4th or early 3rd century BCE, again, probably part of the large building program at the sanctuary around that time. It consisted of four relatively self-contained (the two north and two south wings were separate) two story wings that combined for a total of about 160 rooms. This may have been a means of preventing disease transmission among the visitors. During the Roman period, the Katagotion underwent significant repairs and restorations. In the late antique period, it again fell into disrepair and partially collapsed. Architectural elements from the building were then used for other structures in the sanctuary.

Unfortunately the Katagogion was pretty significantly overgrown when I visited, making it impossible to walk through. I could really only observe it from the perimeter, though there weren’t any actual barriers that prevented access, only the pretty significant growth. This meant that there wasn’t a whole lot to see. I’m not sure if it is normally kept in better condition later in the season, but judging by how well most of the rest of the site was maintained, it seems like a deliberate oversight. Some of the remaining robust walls in the eastern part of this complex apparently date to the Roman rebuilding of the Katagogion.

Continued in Sanctuary of Asclepius Part II

Sources:

Elsner, Jas and Ian Rutherford. Pilgrimage in Graeco-Roman & Early Christian Antiquity: Seeing the Gods. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Kristensen, Troels Myrup. “Mobile Situations: Exedrae as Stages of Gathering in Greek Sanctuaries.” World Archaeology, Vol. 50 No. 1, 2018, pp. 86-99.

Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis, 2.26.7, 2.27, 9.7.5.

Schultz, Peter and Bronwen L. Wickkiser. “Communicating with the Gods in Ancient Greece: The Design and Functions of the ‘Thymele’ at Epidauros”. The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2010, pp. 143-164.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

As usual, great pics and great historical review. I can’t believe you got the theater to yourself for nearly half an hour!

I’ve usually told people that they should rent a car to visit some of the sites near Athens. We did that for Delphi (although our rental broke down in the mountains and we had to have a donkey-riding elderly widow to get us help – but we made it to Delphi in the end!). As you say, the bus system is iffy, and the tours leave you very little time at the site. Thanks again!

Thank you! It’s always nice to hear that people are actually reading and enjoying this! But yeah, it was really a great intersection of being early in the tourist season and just a week or so after targeted opening date for easing travel and tourism restrictions.

I always feel bad, because a lot of my earlier destinations, I relied a lot on public transport, so I have a much better understanding of utilizing that and making recommendations. But, the last few years, I’ve really been heavy on the rental cars because it’s just so much more convenient, and in the end isn’t really that much harder on the budget. In fact, I almost feel like I save money sometimes because I can rent a place to stay outside of city centers away from transit lines and save money on that end. The Delphi trip honestly doesn’t surprise me that much, I had a few iffy rental cars last summer in Greece, particularly in the islands. None broke down, but I also wouldn’t have been totally surprised if they had!