Just to the south of the Capitolium are a few areas to visit Roman remains. The first is right across the street at Via Agostino Gallo 6, at the tourist information office housed at the Palazzo Martinengo Cesaresco Novarino. Housed in the basement and accessible via the tourist office are some remains associated with the forum, decumanus maximus, and a bathing complex of Brixia, dating to various periods of imperial era occupation. The remains can be visited during the hours of the tourist office, which seems to be about 10:00 to 17:00. There is no admission charge, but the remains must be visited with a guide. The guide I went with was very insistent about me not being allowed to take pictures, unfortunately, so, little remains to dissect visually. He also didn’t seem to be particularly enthralled with having to take me down there in the first place and so was very impatient to get it all over with. It was an interesting bit of stuff to look at, from what I remember, so it’s unfortunate that the overall experience of that particular visit was so lackluster. Definitely worth checking out, if only to take a quick peak.

Right across the aptly named Piazza del Foro are some more remains of Brixa’s forum. These, though, are set in an open area on the east side of the piazza, standing in a sunken area a few meters below the street level. Preserved in this area is part of the portico of the forum (partially reconstructed), along with a small section of the steps that would have lead from the portico down onto the paving of the forum. This area is in a public space, and so the remains of the forum here can be viewed at any time, though there is not direct access to the features.

The final remains before heading to the museum are those of the basilica, located a few blocks south along Via Agostino Gallo. Incorporated into the façade of the building on the north side of Piazetta Giovanni Labus, are remains of the south façade of the basilica. The building, appropriately, houses the Brescia office of the archaeological superintendency. The basilica was constructed in the Flavian period at the southern extent of Brixia’s forum. Some of the façade and the pavement around the outside of the basilica below the modern ground level have also been exposed and are visible to look down onto. Apparently, there are more remains of this building and an earlier building, according to the on-site informational sign, in the archaeological superintendency office, which is not open to the general public at will. One might be able to arrange a visit, though. The exterior remains, however, are adjacent to a public space and can be viewed at any time.

Museo di Santa Giulia

The final stop for Roman Brixia is the Museo di Santa Giulia, located at Via dei Musei 81. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10:00 to 18:00 year round. It is closed on non-holiday Mondays. Admission is 10 Euros, which seems a bit steep, but is very much well worth the price. This is honestly one of the better museums I’ve come across in all of Italy, outside of Rome. It’s not completely an archaeological museum, but, the archaeological sections here are quite extensive. A big reason why I felt it necessary to break the Brixia visit up into two blog posts, with the vast majority of one of those being dedicated to the museum.

In addition to a wide and varied collection that includes ceramics, small finds, inscriptions, architectural fragments, sculptural pieces, and all the trappings one might expect at a significant, there are a number of objects and collections that are worth mentioning in particular. The first of these is the bronze object horde found in the excavations of the Brixia Capitolium on July 20th, 1826. There are a number of bronze decorative elements, some with some pretty intricate design components, as well as a large number of cornices. Among the bronze finds, as well, were 6 portraits; two dating to the Flavian period depicting a female Flavian and Septimius Severus, and four dating to the late 3rd century depicting Marcus Aurelius Probus and Claudius Gothicus (two of each). All except the Flavian woman are gilt, with significant amounts of gilding remaining on most of them.

Also among these bronzes was a nearly complete bronze statue of Victory, mentioned in the previous post when discussing the Capitolium. Cast using the lost wax method, the statue seems to have been created in the 2nd century CE by an Italian workshop. The wings may not have been part of the original statue and were later added. It’s likely that Victory was holding a shield, perhaps inscribed with the details of the victory for which she was commissioned. It has also been proposed that she was holding the reigns of a quadriga, elements of which may be among the other bronze fragments found in the Capitolium.

An adjacent area to the bronze finds also contains some finds from the Republican sanctuary, including several large sections of wall painting from the cellae of the temple, including some of those that have been excavated but are not part of the archaeological area. There are a few other fragments of the Republican sanctuary decoration displayed in other parts of the museum.

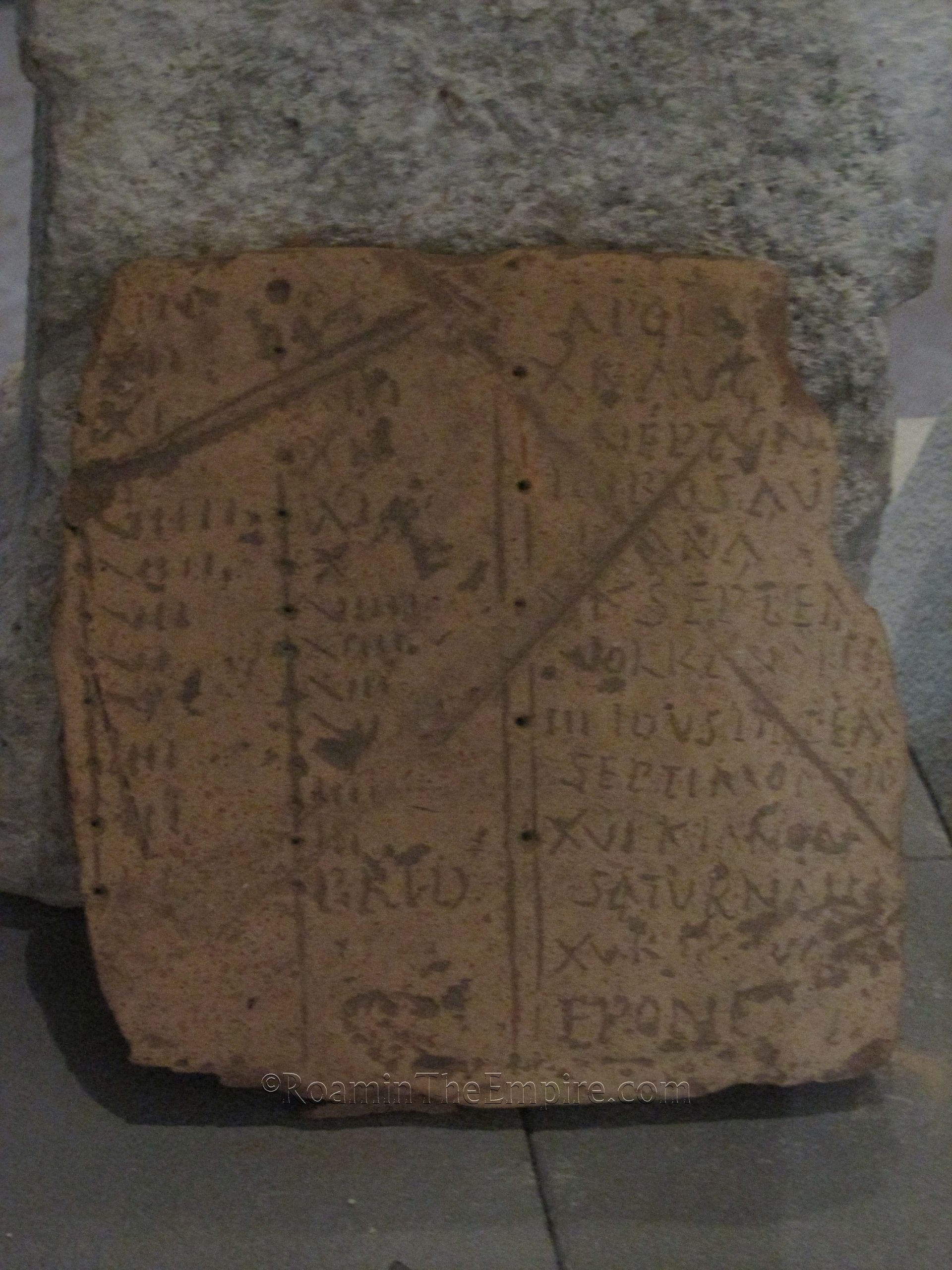

Another particularly interesting object is the Guidizzolo Fasti. This small terracotta tablet is a fragment of a domestic calendar marking the festivals. The latter parts of November and December are visible on the tablet, including the legible festivals of the Saturnalia on December 17th and a festival to Epona on December 18th. Holes next to the dates are thought to be spots for a peg or marker of some sort to be used in marking the current day. It was found in Guidizzolo and dates to sometime after 8 BCE, when the month of August was introduced to the Roman calendar.

Two distinct archaeological areas are also contained within the grounds of the museum, which can be seen as part of the museum visit. The first is the monastery garden road and the Santa Giulia Domus. The monastery garden road a cardo that seems to have been constructed about the time of Augustus. The road was buried in the Lombard period, but the route continued to be used and became the present day Vicolo Settentrionale, which dead ends at the front of the museum, but in antiquity would have continued through the gardens. Part of the road as well as the eastern crepido stones and some adjacent constructions are visible.

Nearby is the Santa Giulia Domus, a private dwelling. What remains of this house is a few fragments of walls and a relatively large intact section of mosaic flooring. The domus was largely abandoned sometime in the 4th or 5th century CE, but later Lombard occupation left post hole perforations visible in the mosaic.

The second archaeological area is the Domus dell’Ortaglia in the northeast part of the monastery complex. This area actually consists of two separate houses, the Domus of the Fountains and the Domus of Dionysus. The Domus of the Fountains, the larger of the two houses, seems to have originally been constructed in the 1st century BCE and was occupied until the 4th century CE, with various building phases discernible over the 5 centuries of occupation. As the name suggests, one of the features of this house is several fountains placed throughout it, though the marble comprising these fountains was largely spoliated.

The smaller Domus of Dionysus was built in the 2nd century CE and in use until the 4th century CE. This house gets its name from a mosaic in the triclinium with a central panel depicting a reclining Dionysus and his panther. Frescos of sea life and pastoral scenes decorate the walls of the triclinium. Another interesting feature of the house is Courtyard of the Pygmies, a courtyard area with Nilotic themed wall decoration, including a priest of Isis. A niche on the wall may have served as a small shrine to an Egyptian god, perhaps Isis.

Both of the houses have ample remains of intact wall and floor decorations. Remains of a hypocaust system are visible in one of the rooms of the House of Dionysus. There are quite a few informational signs present in English and Italian, with detailed explanations of most, if not all, of the rooms excavated for the two residences.

A number of other mosaics are also housed in the museum from Brixia and the surrounding areas. While many of the artifacts in the Museo di Santa Giulia are from the city, there are also quite a few from the surrounding region. Other interesting finds include a bronze land register from Verona, a 1st century BCE bilingual Gallic-Latin stele from Vercelli, some fine late antique ivory objects, and a dedication to the Fatae, which were popularly venerated in the area of Brixia.

There are both pre and post Roman artifacts and art in the museum as well. All told, it took me about four and a half hours to get through the Museo di Santa Giulia, which isn’t a whole lot shorter than the time it took me to go through the Musei Capitolini in Rome later that summer. Had I spent more time with the post-Roman art, it likely would have taken quite a bit longer. There were English translations of pretty much all the objects in the museum that had information in the first place (which was nearly all of them). This really is a top flight museum and not to be missed.

Sources:

Catullus, Carmen 67.

Josephus. Bellum Judaicum, 4.545.

Livy. Ab Urbe Condita, 5.35, 21.25, 32.30.

Pliny the Elder. Historiae Naturalis, 3.23.

Ptolemy. Geographica, 3.1.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Tacitus. Historiae, 3.27.