History

Standing in the alpine foothills above the Principality of Monaco, in the small French town of La Turbie, is one of the few remaining trophies from the Roman world; the Tropaeum Alpium. Known locally as le Trophée des Alpes, the Tropaeum Alpium (also called the Tropaeum Augusti) was constructed on order of Augustus in his 17th year as tribune, placing the beginning of its construction in either late 7 BCE or early 6 BCE. It likely took at least a few years to complete, but the final date of construction is not recorded. Augustus commissioned the Tropaeum Alpium to commemorate his victory in campaigns between 25 BCE and 14 BCE against 45 local Alpine tribes. Though the inscription that records those tribes was incredibly fragmentary, the names and dedication are preserved by Pliny the Elder in Naturalis Historia, and allowed the inscription to be reconstructed from ancient and modern pieces.

The trophy was placed at the highest point on the Via Julia Augusta (constructed a few prior, starting in 13 BCE) as it ran from Placentia (Piacenza) to Arelate (Arles). The monument sits on a 500 meter high ridge of Mont Agel, a 1,148 meter summit nearby. It was also essentially a boundary point between Italia and Gallia. The place of the Tropaeum Alpium is designated on the Itinerarium Antonini Augusti as Alpis Summa, a mansio located between Albintimilium (Ventimiglia) and Cemelenum (Nice).

The campaigns that are celebrated on the trophy began in 25 BCE when Augustus dispatched an army to the modern Val d’Aosta area to fight the Salassi tribe, one of many that were using the limited number of usable Alpine passes to extract tolls on commercial and military traffic passing through them, as the Romans only had control over a route passing along the Mediterranean. That operation was successful and a number of smaller consolidations followed. The most widespread and ambitious of the campaigns associated with the subjugation of the Alpine tribes came in 15 BCE, when Augustus employed both Drusus and Tiberius in a wide-ranging push throughout the Alpine region, most notably against the Vindelici in the area between the Rhine Valley and Lake Constance.

Following the fall of Roman power in the area, the Tropaeum Alpium suffered somewhat. It was interpreted by Christians as a pagan temple to Apollo, and as such was the focus of destructive activities. The main form survived and in the 13th century the trophy was re-purposed as a fortification. During the War of Spanish Succession in the early 18th century, it was ordered destroyed along with other fortifications in the area; while the core of the structure largely survived, it did incur significant damage. At this point, the Tropaeum Alpium became a quarry for building. Many of the houses in the area, and the adjacent Église Saint-Michel de La Turbie were built using blocks that originate from the trophy. The mid-19th century brought some efforts to restore, or at least prevent the further deterioration of the monument, but it wasn’t until the early 20th century that serious efforts were made to restore it. This occurred due to the interest and monetary investment of an American patron (Dr. Edward Tuck) and the work of a French archaeologist (Philippe Casimir). The restoration and rebuilding of the Tropeaum Alpium was finished in 1934.

Getting There: From Nice, there is a bus that runs to La Turbie a few times a day. The T66 bus leaves from the Pont Michel transit hub in the northeast part of the city toward La Turbie/Peille a few times a day. This station is connected to the center of the city by tram and bus. The 116 line also leaves from Vauban bus station, which is also connected to the rest of the city by tram and bus. The T66 line takes about 35 minutes to get to La Turbie, while the 116 (which starts a little further south) takes about 45 minutes. The Lignes D’Azur schedule website can be a bit temperamental, but that is the best place to check the exact schedule. Failing that, a PDF of the schedule, though it is a few years old, seems to still be accurate and can be found here.

Tropaeum Alpium

The Tropaeum Alpium is located at Avenue Prince Albert Ier de Monaco, which runs on the north side of the park that contains it. This is the point at which the trophy is accessible. There is an entrance/exit on the west side of the park, but this is not used as an entrance anymore, but can be used to leave. The Tropaeum Alpium is open during the summer (mid-May to mid-September) from 9:30 to 13:00 and 14:30 to 18:30. The rest of the year the hours are 10:00 to 13:30 and 14:30 to 17:00. It is open Tuesday through Sunday, and closed on Mondays year round. Admission to the monument is 6 Euros.

The area around the Tropaeum Alpium was likely cut and leveled in antiquity. The Via Julia Augusta passed by the monument on the west side. The entrance is at a slightly lower elevation, so one must climb the hill a bit more to reach the trophy. Along the way, and along the eastern side of the park, due south of the entrance gate, there are spectacular views of Monaco and the coast.

The trophy itself originally stood to a height of 50 meters, though today it is missing the entirety of its conical roof and the topping statue, leaving it at only 35 meters. The west face of the Tropaeum Alpium is the most completely preserved/restored. The other faces are in varying states of completion. This, however, allows for the visitor to see the varying layers of construction of the trophy. The east and northern faces give a pretty good idea of the construction of the core of the monument, which was quite different from the polished exterior. The south face preserves an entry doorway (though the bronze door is modern) and the space that held the original staircase up to the top of the podium, which no longer survives.

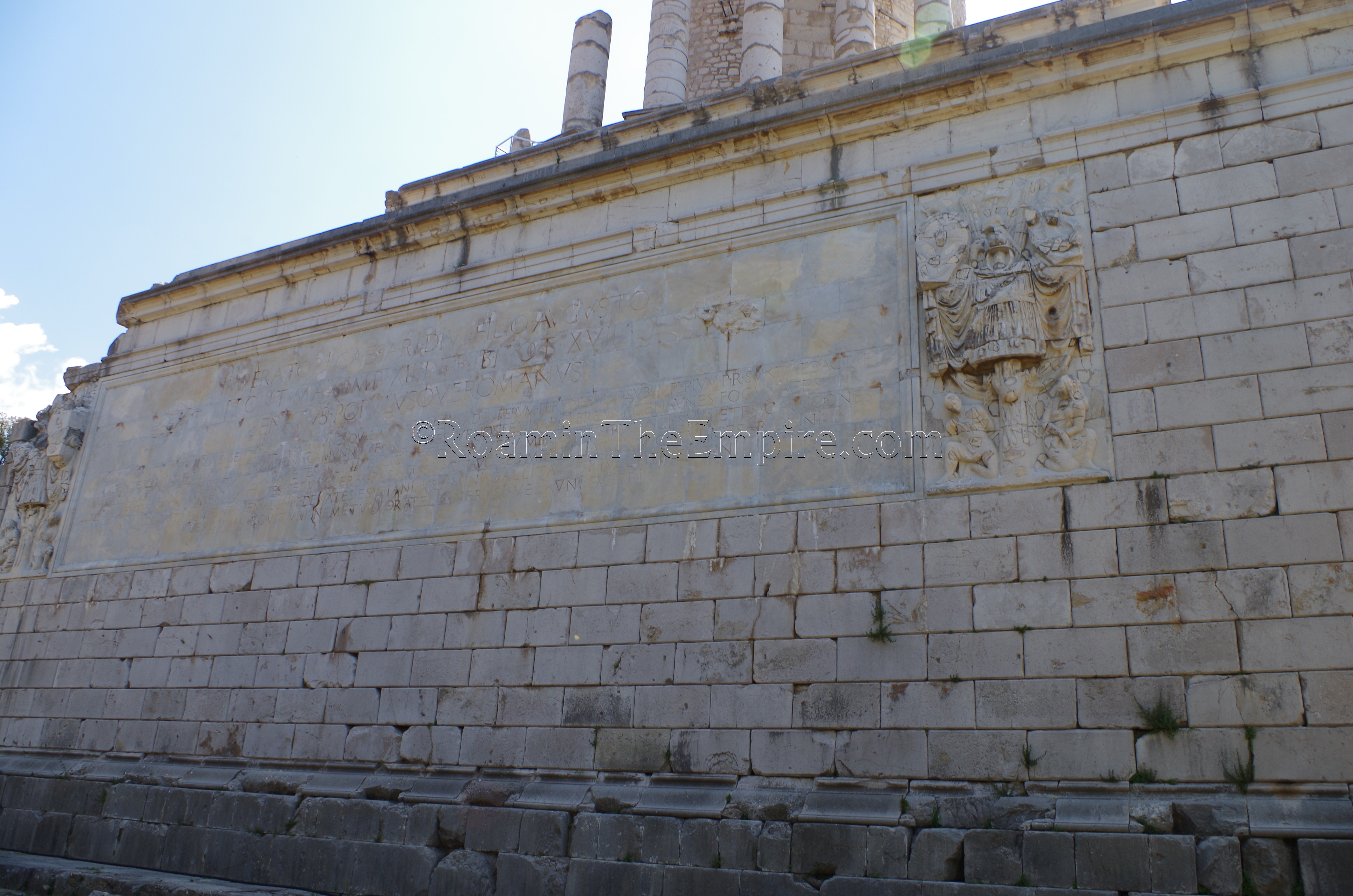

On the west face, which would have faced the Via Julia Augusta, is the inscription that lists the tribes that were subjugated by Augustus. Some of the fragments of the inscription are original, while others are modern replicas used to fill in the pieces that were not able to be located. The inscription is flanked by reliefs that depict captives kneeling beneath a traditional tropaeum. These too are incredibly fragmentary, and it’s easy to see in these reliefs how few pieces of the original remain, and how much is reconstructed based on typical motifs present in other areas.

The trophy consists of a large first podium, a smaller second podium, a colonnaded rotunda, a topping drum, and a conical roof. One can enter via staircase on the south side of the monument that leads up to the top of the second podium. From there a small staircase leads up the base of the rotunda and one can view the reconstructed colonnade of the rotunda, which would have likely originally included niches for statues of generals, but which is not represented in the reconstruction. A path also leads to the east side of the rotunda, which is not reconstructed, where there is a platform for viewing the town and coast.

There is a small museum (though it is more of antiquarium) on site. Most of what is here are some fragments of the trophy not used in its reconstruction and a model of what it would have looked like in antiquity. There are also a few small votive and funerary inscriptions of soldiers that came from nearby burials. Though the funerary inscription could have been that of a soldier involved in the actual conquest of the area, the votive inscription was much too late, and illustrates the continuing interest of soldiers in the monument.

Spolia from the earlier destructions of the Tropaeum Alpium is evident in some of the buildings surrounding it. Apparently, some buildings were destroyed to recover the materials (and later rebuilt anew) when the 20th century reconstruction was occurring. One of the most obvious uses of the material is in the Église Saint-Michel de La Turbie, the church just to the southwest. The lower courses of the church construction on the west side are exposed, revealing the clear re-use of the tropaeum construction materials.

While the marble used in the monument was imported from Italy, the limestone was quarried locally. One of these quarries is a relatively brief 1.5 kilometer/20 minute walk from the tropaeum, downhill toward Monaco. There is open access to the quarry, as it is on public land and there are no kind of entrance restrictions. As such, it’s not in the best of shape, it’s obviously a place where locals go to hang out and drink. There’s lots of garbage and some graffiti. The quarry was also apparently used post-antiquity. But, it is very clearly a quarry and there are supposedly some unfinished/un-useable column drums scattered around somewhere, though I was unable to find any.

Quarry

To get back, one can walk back up to La Turbie, or there is also a bus stop located at the top of Chemin des Carrières Romaines, where that road intersects with the D53 and branches off toward the quarry. Bus 11 running along this route goes down to the tourist office in Monte Carlo, which is not far from the train station where one can get back to Nice.

The Tropeaum Alpium really isn’t that difficult to visit whether one is in Monaco or Nice, and given not only the significance of the monument, but the spectacular views it affords of the French Riviera, it’s well worth carving out a half a day to go see.

Sources:

Bromwich, James. The Roman Remains of Southern France: A Guidebook. London: Routledge, 1996.

Everitt, Anthony. Augustus. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2006.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictioniary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

King, Anthony. Roman Gaul and Germany. University of California Press, 1990.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.