Most Recent Visit: June 2017.

About 11 kilometers to the east of the modern town of Termini Imerese are the remains of ancient Himera. After a crushing Carthaginian defeat at Himera at the hands of the combined forces of Gelon of Syracuse and Theron of Akragas in 480 BCE ended the First Sicilian War between the Carthaginians and Greeks in Sicily, the Carthaginians once again sought to take the city near the outset of the second major conflict between the powers on the island, the Second Sicilian War. After first sacking Selinus in accordance with the Carthaginian mandate for the army (which was assisting Segesta against Selinus), Hannibal Mago, grandson of the commander who lost and was killed at Himera in 480 BCE, marched to Himera, perhaps intent on avenging the previous defeat. The numerically superior Carthaginian force, despite a Greek surprise attack that initially threw the Carthaginian forces into such disarray that they ended up fighting each other, was victorious, though with heavy losses, and took the city after a short 1 day siege following the withdrawal of the surviving Greek forces. As retribution for the loss in 480 BCE, Hannibal Mago had 3,000 Greek prisoners sacrificed on the site of his grandfather’s death, the city was razed, including the temples, and the inhabitants were all sold into slavery.

At some point following this episode, some surviving inhabitants of Himera, who apparently managed to flee the city before its fall and avoid the fate of those captured and sold into slavery, moved up the coast to the site of modern Termini Imerese to found a new settlement. The exact mechanism of this is disputed, as Cicero notes that the survivors took it upon themselves to found the town, while Diodorus says the Carthaginians founded the settlement, with Carthaginians settlers, in 407 BCE at that location to prevent a reoccupation of the site of Himera. A treaty in 405 BCE between the Carthaginians and Greeks specifically allows the return of exiled citizens to their homes in Selunite, Akragas, and Himera in return for allegiance to Carthage and a prohibition on the building of fortifications. It is likely that there is truth to both accounts and that the city was founded with both survivors and Carthaginians.

Various names have been given for it, including Thermae, Therma, Thermae Himerenses, and Thermitanus. The ‘thermae’ designation that prevails through all the names is in reference to a natural hot spring that occurs at the site. For the sake of clarity, since ‘thermae’ refers broadly to a bathing complex or springs, Thermae Himerenses is typically the moniker of choice. These natural hot springs were mythologically discovered by Hercules during his wanderings on Sicily, according to Diodorus Siculus, and are mentioned by Pindar in his Olympian Ode XII to Ergoteles of Himera. Because the new town of Thermae Himerenses was founded with inhabitants of Himera, the new town is sometimes even referred to as Himera, even after the point of Himera’s destruction.

The town seems to have quickly grown and flourished, remaining for the most part under Carthaginian control, though the areas of influence fluctuated from time to time during the Sicilian Wars, and particularly the protracted conflict that followed the destruction of Himera. Thermae Himerenses is said to have initially sided with Dionysus after his campaign against the Carthaginians in 397 BCE (and is not among the cities that remained loyal following the destruction of Motya in 396 BCE), but apparently returned to the Carthaginian fold not long after. Other than that it doesn’t seem to have played any particular part in those conflicts nor the following Pyrrhic Expedition, though it can be assumed that it was nominally controlled by Pyrrhus at some point, as Lilybaeum was said to be the last remaining Carthaginian settlement still controlled by the Carthaginians before Pyrrhus left the island.

During the first Punic war, Thermae Himerenses was the site of a battle between a Roman force and a Carthaginian army under the command of a Hamlicar (not Hannibal’s father, who was not yet in Sicily) in 260 BCE. Though the details of the battle are not mentioned, the Romans were advancing on the city when they were met by the Carthaginians, and were overwhelmingly defeated, losing 6,000 men, nearly the entirety of the force in the battle. In 254 BCE, the Romans were once again moving on Thermae Himerenses. The Romans attempted to take the city by subterfuge, capturing the gate keeper when he left his post to relieve himself outside the city walls. They convinced him to open the city gates to them at an agreed upon time at night, which he did, letting in 1,000 Romans. Those Romans, however, insisted that the gates be closed and locked behind them, not wishing to share the loot with the rest of the army. The mechanism by which the Romans were discovered and killed is not mentioned by Diodorus, but, the story goes that they were all slaughtered within the city; a fitting end for their greed. By 252 BCE, the Romans had besieged and taken control of the city.

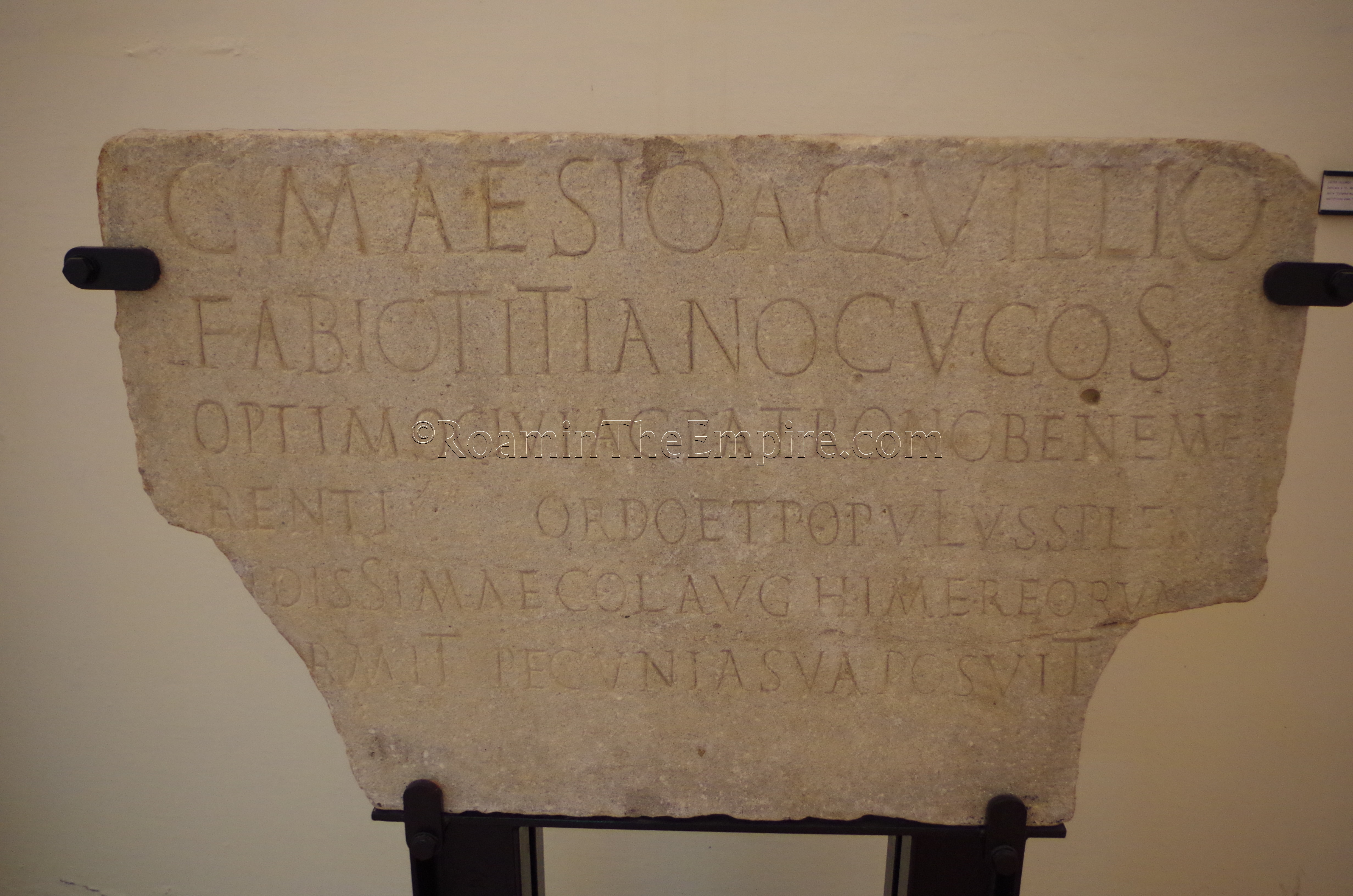

Under Roman control, Thermae Himerenses seems to have become a thriving settlement by the middle of the 1st century BCE. Cicero makes a few mentions of the city, stating that the city enjoyed a special status that allowed it the use of its own laws and a restoration of its territory because of the city’s loyalty; the origin of which is not made immediately clear. The city was certainly on the Carthaginian side through a good portion of the First Punic War and was never really in play during the Second Punic War, but, perhaps the fidelity of the city was tested in some way during the First Servile War. He also notes that following the Roman victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War, Scipio Africanus restored some statues to the people of Thermae Himerenses that were looted from Himera and taken back to Carthage after the destruction of the former. An inscription noting the Coloniae Augustae Himeraeorum Thermitanorum seems to indicate that the city received a colony during the reign of Augustus. Other than strictly geographic mentions in Pliny, Ptolemy, and various Itineraries, there does not seem to be much later mention of the city, though it appears to have continued to be occupied without break from antiquity to present day.

Getting There: Termini Imerese is about 40 kilometers from Palermo and can be reached in about 40 minutes via the E90 highway. The SS113 is also an option, but is a bit slower at an hour. The city is well-connected to Palermo via train, with at least 2-3 departures per hour between 5:00 and 21:30. The journey takes between 24 and 51 minutes depending on the train, but costs 3.80 Euro no matter which train, so planning ahead to get a faster train is advisable. Return trips to Palermo are just as frequent and varied, but also cost only 3.80 Euro. The schedules can be found at the Trenitalia website. One unfortunate aspect of this method is that the train station is not especially close to most of the Roman remains, which would require a 1.3 kilometer walk with a 70 meter elevation increase. There is likely bus service from the train station up the hill to the historic center of the city, but, there is little information online. Similarly, there is likely bus service between Palermo and Termini Imerese, perhaps directly to the center, but the online information is lacking.

Though the consistent occupation of Termini Imerese has erased much of the vestiges of the city’s past, there are a few things to be seen here. Like most cities of any reasonable size in Italy, there is an archaeological museum or, in this and some other cases, a civic museum with a reasonably sized archaeological collection. The Museo Civico ‘B. Romano’ is located, appropriately, on Via Marco Tullio Cicerone. Though there is no street number assigned, the street is short and the museum is pretty easy to find once on it. The museum is open Tuesday to Saturday from 9:00 to 13:00 and 16:00 to 18:30. On Sundays it is open from 8:00 to 12:30. The museum is closed on Mondays. Admission is 1.50 Euro.

The museum is quite small, but, there are certainly some nice pieces in it. The previously mentioned inscription noting the Coloniae Augustae Himeraeorum Thermitanorum name is on display here. There are also a few portrait busts, including one of Tiberius, and some fragmentary pieces of sculpture. A small collection of funerary inscriptions, some small finds, and a few architectural pieces round out the majority of the objects in the collection. Being a civic museum, it is not solely dedicated to the archaeology of antiquity, so there are also finds from other periods as well as a general art collection. It takes maybe about 10-20 minutes to get through the Roman collection here. Just about all the information is in Italian, which isn’t altogether surprising. I also feel inclined to not that the staff is quite friendly and seemed especially happy to have foreign visitors; they were quite pleased to take us into the locked up secondary building to show us the collection there as well. For the price, it’s certainly worth the stop.

Nearby are the fragmentary remains of the 1st century CE amphitheater. The main portion, representing what is left of the southwestern corner of the amphitheater, is located on the northeast corner of Via Anfiteatro and Via Garibaldi, just a 5 minute walk from the museum. Piers supporting the cavea of the amphitheater can be seen here in a small gated park. The buildings and streets in this area (Via Anfiteatro and Via S. Marco) still hold retain the shape of the northern half of the amphitheater, and walking along these streets, occasional remains can be seen; some incorporated into the modern buildings. In the middle of these buildings, accessible via a small alley at the northernmost point, some more remains can be seen in a recessed area in a small courtyard/piazza area designated as Piano Barlaci.

A few minutes to the north of the amphitheater, in the Villa Communale park, are the remains of some Roman structures. The park may also be identified as the Villa Nicolò Palmeri. While the remains are essentially due north of the amphitheater, the park can only be accessed via an entrance further to the east or from Via Garabaldi, to the west of the park area which contains the amphitheater remains. It is a public park, so there is no admission or limited access, though it does seem to only be open between 8:00 and 20:00, though daylight may dictate hours outside of these. What exactly the remains here are is a matter of some speculation, but the most likely supposition is that they are administrative buildings, perhaps the city’s curia. Despite the fact that it is a public park, the remains seem to be in relatively good shape (I didn’t notice any modern graffiti) and the grounds are kept up fairly well.

Outside of the historic city center, there are a few remains of the aqueduct that fed the city, the so-called Cornelius Aqueduct. The aqueduct was constructed in the 1st century BCE to bring water to Thermae Himerenses from the Brucato springs at the foot of Mount San Calogero about 8 kilometers away. The aqueduct was actually still in use until 1388, when it was partially destroyed by the Anjou to end a siege of the city. The first visible section of the aqueduct is in the lower town at the intersection of the aptly named Via Acquedotto Romano and Via Giovanni Falcone e Paolo Borsellino (which is also part of the SP113 designation). There is about a 115 meter stretch of single arches (including a turn) that are mostly visible, as well as some further remains in a semi-private parking lot of a grocery store. Granted, there’s probably a significant amount of later reconstruction and refurbishment given it was in use for at least 1400 years, but its origins are most certainly Roman. There is also a large fragment of some sort of construction in the field to the south of the aqueduct, and while it appears as though it could be ancient, there doesn’t seem to be much information on it.

The second section of the aqueduct is a bit more difficult to see, as it is outside of the town. Just to the south of the on-ramp/off-ramp of the E90 highway for the town is a double arched bridge crossing the valley here. This section of the aqueduct was apparently in use until the mid-1800’s. Unfortunately, even with a vehicle, it seems it is difficult to see, as the rural roads in that area are a bit difficult to navigate and I couldn’t find any way to get closer to it without going on possibly private roads and risking the displeasure of the locals. It is visible from the on-ramp/off-ramp, though, but shooting from a moving vehicle is not ideal, as evidenced by my own attempt.

Sources:

Cicero, In Verrem, 2.2.35-37, 2.2.47-48, 2.2.76, 2.4.34.

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, 4.23, 13.79, 19.31, 19.71, 23.9, 23.19-20.

Pindar, Olympian XII.

Polybius, Historia, 1.24, 1.39.

Ptolemy, Geographia, 3.4.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.