Most Recent Visit: June 2016

The site of modern day Barcelona seems to have been occupied well before the arrival of the Romans. According to legend, a city was founded on the location by Hercules. Another legend places the name Barcino as being derived from the Carthaginian Barcid family and was founded by Hamilcar Barca. The Carthaginian link seems unlikely, but rather a name known from Iberian coinage, Barkeno, may have been the Iberian settlement of the Laietani that preceded Roman Barcino in the 3rd century BCE.

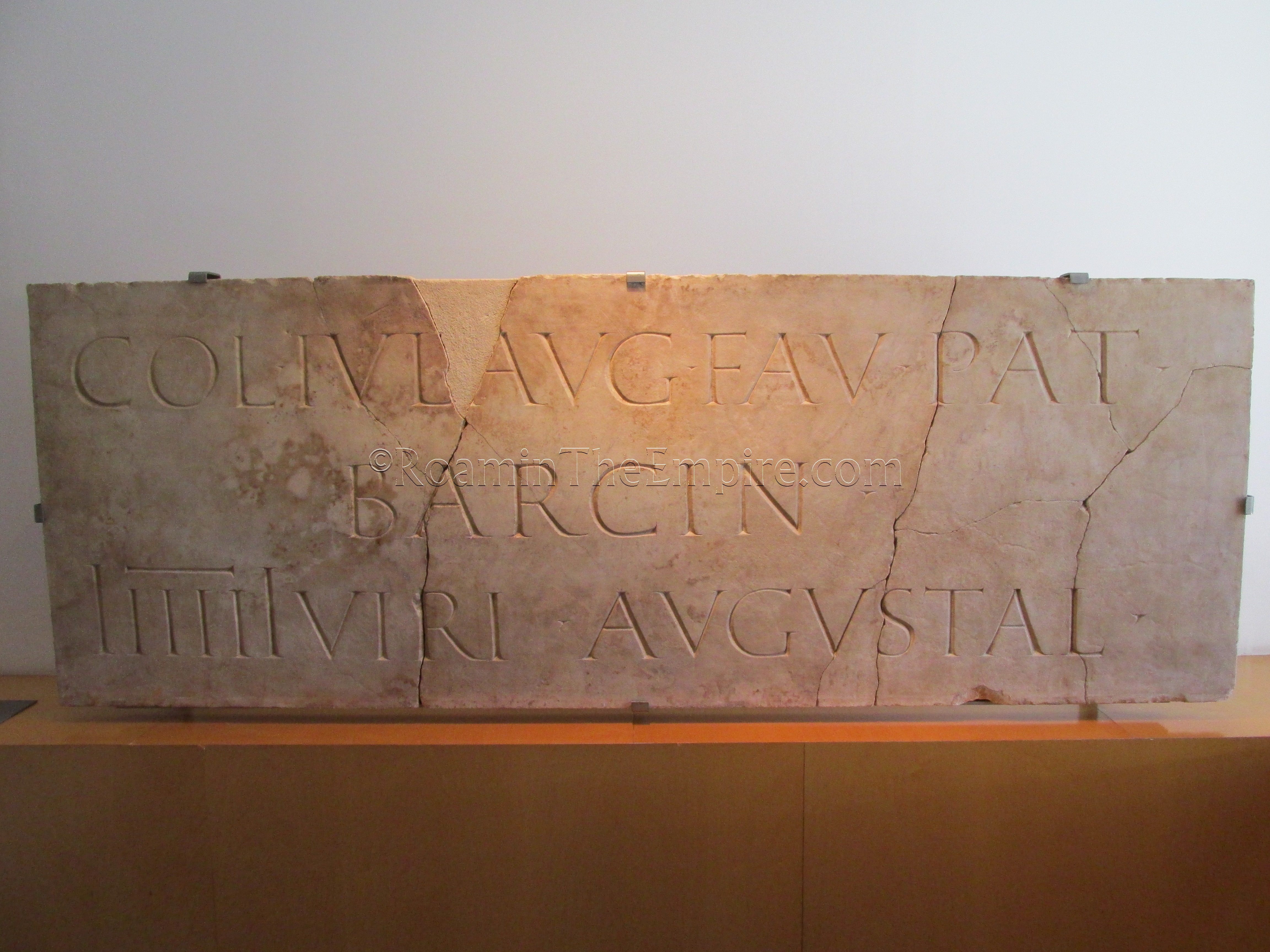

The Roman city of Barcino was founded on the Mons Tabar during the reign of Augustus as the Colonia Faventia Julia Augusta Pia Barcino or alternatively referred to as the Colonia Julia Augusta Faventia Paterna Barcino. The colony probably consisted of veterans from the Cantabrian Wars. It is mentioned briefly in Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela’s catalogue of Roman settlements in that part of Spain in their respective works. Barcino was apparently renowned for the wealth of its citizens, fertile surroundings, and a well-protected port. In 265 CE, the city was sacked and destroyed by the Franks and Alamanni, though it was later rebuilt with more robust fortifications. The citizens apparently dismantled some monuments before the arrival of the barbarians in an attempt to bolster their defenses with the stone. A later mention by Avienus suggests that the settlement was still prosperous after the sack and rebuild. Barcino was peacefully occupied by the Visigoths in the 5th century CE, and the Visigoth king, Ataulf, was assassinated there in 414 CE.

Getting There: Barcelona is well connected to the rest of Spain and Europe. There is a major airport connected to the city center by metro, and a smaller airport in Girona, served by buses between the cities, where budget airlines often fly into. Behind Madrid, Barcelona is the second largest rail hub in the country, so it is well served by trains to and from other parts of the country.

The Roman city of Barcino occupied what is now the Barri Gòtic, the Gothic neighborhood of Barcelona. The orthogonal street layout and the rectangular shape of the city are still reflected in the street plan of the central part of the Barri Gòtic. Since the Roman walls were incorporated into the later medieval walls, the area remained the core of the city long after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Roman remains of Barcino’s walls can be found at various points around this circuit, mostly dating, apparently, to the third century CE bolstering of the walls either before or after the sack of the city in 265 CE. The circuit of the walls runs about 1,3500 meters around the core of the Barri Gòtic, reaching a thickness of about 2 meters in some places.

The most prominent portions of Barcino’s walls (and later additions) can be found off of Placita de la Seu, north of the cathedral. On the south side of Plaça Nova, Carrer del Bisbe passes through the remains of one of the gates (porta decumana occidental) of the wall, the Torres Romanes. It is at this point that a small, two arched section of a Roman era aqueduct can be seen running into the walls as well, just to the left of the northern most of the two gate towers. Following the course of the walls in a northeastern direction, two defensive towers, of an estimated 60-78 towers that were built into the circuit of the walls, are present. The lower portion of the walls made up of larger blocks are the Roman phase of building, while the smaller block construction of the upper parts of the wall are later phases.

The wall disappears in front of the cathedral but pick up again with a section that includes another defensive tower at the point where Carrer de la Tapineria intersects with the plaza. Following Carrer de la Tapineria away from Placita de la Seu, more sections of the wall can be seen on the west side of the road before reaching Plaça De Ramon Berenguer El Gran, where another significant portion of the walls can be found, including another few defensive towers.

The walls continue and are visible at various points in the Barri Gòtic, but in the interest of not getting bogged down in intricate directions and repetitive descriptions, I’ve included a map with points at which segments of the walls can be found.

Near the cathedral, at Plaça del Rei s/n, is the Museu d’Història de Barcelona (MUHBA), a museum devoted to the history of the city, including the Roman period. The museum is open from Tuesday to Saturday between 10:00 and 19:00 and on Sunday from 10:00 to 20:00. It is closed on Mondays. Admission to the museum is 7 Euros, but is free after 15:00 on Sundays.

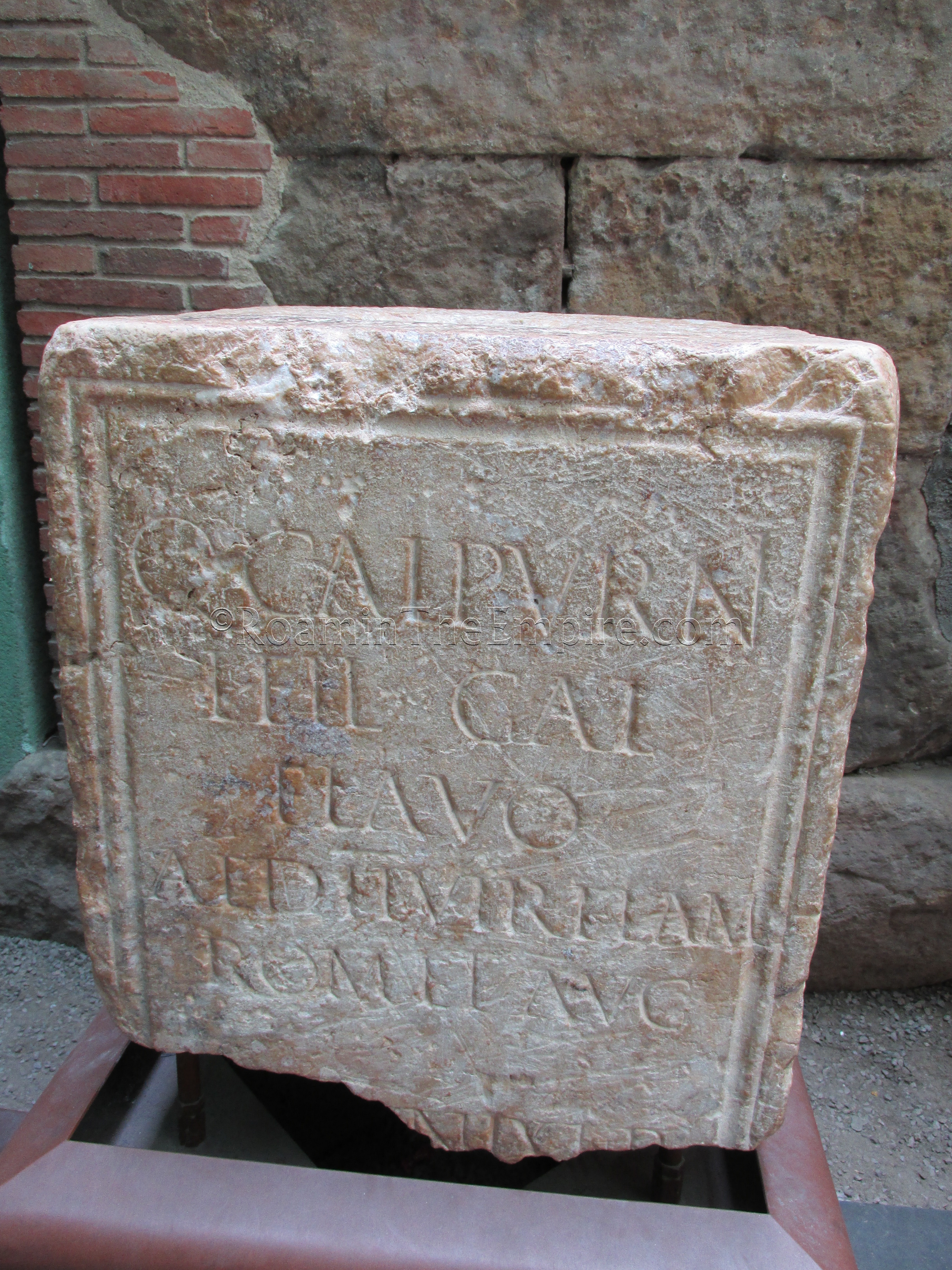

The artifact collection at this museum is not especially large, but there are some nice and relevant pieces. After all, this is not an archaeological museum in the traditional sense, it is a museum presenting the history of the city, and as such, the artifacts are presented in a bit of a more sparing way.

The real treat at the MUHBA is the archaeological excavation in the basement. After passing through the Roman artifact collection, one descends beneath the museum to the excavations that have uncovered a series of occupation layers dating back to the founding of the Barcino through about the 7th century CE. The area occupies the northern corner of the city, nestled up against the city walls, some remainders of which can be seen, including a section dated to about 15-10 BCE, which would put it at about the foundation of the city. Later sections of the wall, including a 4th century CE tower, are also accessible.

Most of what remains here are a series of industrial areas along the intervallum road running along the interior of Barcino’s city walls. These include a fullonica and tinctoria dating to the last half of the 2nd century CE, a garum factory dating to the 3rd century CE and, wine production facilities dating to the last part of the 3rd century CE or early 4th century CE. The visit is set up in a way so that different parts of each of these facilities can be seen, which is particularly interesting for the garum and wine production areas, which are relatively extensive and complete.

To latter stages of the excavations largely feature areas associated with the early Christian structures in the vicinity of the cathedral, dating to the 5th through 7th centuries CE. Among these structures, there is also a section of mosaic and part of a peristyle associated with a Roman domus upon which the Episcopal Palace was built. The reuse of Roman materials, inscriptions in particular, is also evident in this area. The excavations and artifact collection are both well signed and include descriptions in English, Spanish, and Catalan. The excavations include helpful diagrams and reconstructions to help contextualize the remains. At 7 Euros, this is actually one of the pricier stops I had in Spain, but the admission is well worth it; the material and excavations are presented in a detailed and modern way. In all, I spent about an hour and a half here, though I was a bit rushed to try and get all the Barcelona sites in an afternoon, so that I had the next day to visit Empuries. An hour and a half is probably a good average, though I’m sure, under less of a time constraint, I probably could have spent longer.

Nearby in a small courtyard to the southwest of the MUHBA and southeast of the cathedral is a small courtyard at Carrer del Paradís 10. Within the courtyard are some restored columns belonging to the Temple of Augustus that was located in the forum of Barcino. The site is administered by MUHBA, and though there is no entrance fee, it does have a gated entrance that is shut and locked outside of opening hours. The site is open on Mondays from 10:00 to 14:00, Tuesday to Saturday from 10:00 to 19:00, and on Sundays and holidays from 10:00 to 16:00. Even outside of these hours, part of the temple can be seen through the gate; my first visit to the city in 2008, I didn’t discover it until my last day in the city, so I had to be satisfied with the view from outside the gate until my most recent visit.

This northern corner of the temple with four columns standing on a 3 meter high podium belonged to a temple dedicated to the imperial cult of Augustus. One of the columns, for many years, was displayed in the Plaça del Rei before it was restored to the temple in 1956. They exact date of construction for the temple seems to be a bit unclear, even among the literature provided by the MUHBA. Some information claims a late 1st century BCE construction date (which would probably be a little early if the temple was originally constructed to be used in the imperial cult) while other information states a later construction during the reign of Tiberius, which seems more likely. There is not a lot of room in the courtyard, so it can get quite crowded during peak hours. There are also some signs that include English translations on-site.

A short distance away at Carrer del Regomir 7-9 is the Centre Civic Pati Llimona, where the Porta de Mar (porta decumanus oriental), a portion of the gate which lead to the port area, stands. While some of it can be seen from outside and through windows, entrance to the civic center is actually north down the small Carrer de Sant Simplici, located off Carrer del Regomir at that address, and just to the west of the remains of the gate that can be seen from the street. On the far end of the courtyard that street leads to, is the entrance to the civic center. Entrance to the civic center is free, but the opening hours are somewhat complicated. I’ve found several different postings for the hours when it is open, but, the only one that I can confirm is that which is listed on the official site of the civic center; Tuesday to Friday from 17:00 to 20:00, as I visited during the time frame on a Tuesday. Other sources state there are morning opening hours during the week, openings during the weekend, and openings only on Tuesday and Thursday.

It is also a working civic center with all sorts of things going on, so, the remains are not even really the focal point of the center in any capacity. There was someone at a reception desk at the entrance that directed me to the remains of the gate when I asked. Down a hallway is a stretch of the city wall, and then part of a tower and the gate. This gate apparently belonged to a phase of the walls constructed at the end of the 1st century and beginning of the 2nd century CE. The later 4th century CE construction on the walls rendered this gate unused and it was walled up. There is also some fragments of a 2nd century CE bathing complex that are supposed to be visible here, but which I was not able to find access to. Pictures on the MUHBA and civic center websites confirm the presence, which looks to possibly be accessible by some kind of stairway, but, there are no indications from the lobby to these remains, and I was unable to convey this to the workers there.

The last site I visited in the Barri Gòtic was the Via Sepulcral Romana at Plaça de la Vila de Madrid. Because of when I was in Barcelona, I wasn’t actually able to enter the site, as it has very strange hours of opening. The site is open on Tuesday and Thursday from 11:00 to 14:00 and Saturday and Sunday from 11:00 to 19:00. Because I arrived in Barcelona on a Tuesday afternoon (getting to the Barri Gòtic just after 14:00, actually), and leaving on Thursday morning, I was completely blocked out of the entrance window. My previous visits to Barcelona, while the necropolis had been excavated at the time, the site was not actually ready for visitation. Fortunately, the actual section of the necropolis is open air and can be viewed from the surrounding plaza. There is an interpretive center with artifacts related to Roman funerary practices, the quality of which I obviously can’t address, but, admission to the site and interpretive center is 2 Euros. The funerary monuments here date from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE.

On the west side of Plaça Del Vuit De Març, embedded in the walls of the building that takes up that side of the square, are the outlines of four arches of an aqueduct that was incorporated into the wall of that building. This is the same aqueduct that enters the walls in Placita de la Seu.

There are two Roman domūs remains in the Barri Gòtic that can be visited, the Domus Avignon and Domus de Sant Honorat. The Domus Avignon is a 1st to 4th century CE dwelling located at Carrer Avinyó 15. while the Domus de Sant Honorat is 4th century CE and located at Carrer de la Fruita 2. Unfortunately I was not able to visit either because of a very restrictive opening schedule. Both only have public openings on Sundays from 10:00 to 14:00. They can also supposedly be visited with prior reservation from Monday to Friday, which I did not attempt to take advantage of because of my compressed visit. Entrance to both is free.

The last place I visited was a bit out of the Barri Gòtic on the slopes of Montjuïc, the Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya (MAC Barcelona). The main archaeological museum for the region of Catalunya, it is located at Passeig de Santa Madrona 39. The museum is open Tuesday to Saturday from 9:30 to 19:00, and on Sundays and holidays from 10:00 to 14:30. It is closed on Monday. Entrance is 5.50 Euro.

The collection here is pretty extensive, and covers prehistory through the Visigoths. As the primary branch of the MAC, the museum collects some of the best archaeological pieces from all over the region (at least from among those that are not in the MAN in Madrid), not just the Barcelona area. There are even some pieces in the collection from further afield in different regions of Spain. The Roman collection contains what one might expect; there are mosaics and some wall paintings, inscriptions, portraits, small bronzes, pottery, and other small finds. There is surprisingly little in the way of large statuary pieces, though there are a few ornate sarcophagi on display.

In addition to the Roman collection, there are fairly large Iberian, Greek, and Punic collections with some nice pieces. Most objects have sufficient descriptions, though the availability of English translations is a little inconsistent; some objects have them while others are only in Catalan and Spanish. I spent close to about 2 hours in the museum, though I was, again, probably moving a little faster than I would have under normal circumstances where I didn’t have any time constraints that day. An hour and a half is the time the museum recommends, and that is probably sufficient for most people. But, I imagine that given a less compressed schedule, I probably would have stretched it to about 2 and a half hours.

Sources:

Avienus, Ora Maritima, 5.520.

Curchin, Leonard A. Roman Spain: Conquest and Assimilation. New York: Routledge, 1991.

MacKendrick, Paul. The Iberian Stones Speak: Archaeology in Spain and Portugal. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1969.

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historiae, 3.4.

Pomponius Mela, Description of the World, 2.6.

Weiss, Arnold H. “The Roman Walls of Barcelona.” Archaeology, vol. 14, no. 3, Sept. 1961, pp. 188–197.