Most Recent Visit: June 2016

Quick Info:

Address:

Calle de Serrano, 13

8001 Madrid

Hours:

Tuesday-Saturday 9:30-20:00

Sunday 9:30-15:00

Monday Closed

Admission: 3 Euros

After spending the morning and the early afternoon in Alcalá de Henares, I decided to head back to Madrid to see the Museo Arqueológico Nacional to try and take it in with the rest of the afternoon. I was already unsure where I’d be able to fit the museum in during my time in Madrid, so I figured taking the first opportunity would probably be the best move on my part. While I was a bit pressed for time on the visit, in hindsight it was definitely the right call to make.

Getting There: The museum is pretty centrally located within Madrid. While not in the very center, it is close to a lot of the other sites in Madrid; right down the street from the Prado museum and the Parque de El Retiro. It is accessible by metro line 2, a few blocks from the Retiro stop, and metro line 4, near the Colón or Serrano stops. It is also close to the Madrid Cercanías stop of Recoletos, which services the C1, C2, C7, C8, and C10 lines. Since I was coming from Alcalá de Henares, I used the Recoletos stop, and it was less than a 5 minute walk to the museum. Over a dozen bus lines also stop nearby. The archaeological museum shares the building with the Museo de la Biblioteca Nacional, and is only accessible from the east side of the building, on Calle de Serrano.

The museum is open from 9:30 to 20:00 on Tuesday through Saturday, and from 9:30 to 15:00 on Sundays and holidays. It is closed on Mondays. Admission to the museum is normally 3 Euros, but is free on Saturday after 14:00 and on Sunday mornings, as well as a few holidays. Current hours and admission (along with the additional free days) can be found on the museum website here.

As one might expect from a national museum in the capital city of country, the collection at the Museo Arqueológico Nacional is quite extensive. There are essentially two main floors of exhibitions in addition to a section on prehistory (pre-Iron Age) taking up part of the ground floor (where the entrance is located) and a basement exhibition area on numismatics. The Roman Hispania collection takes up about a third of the first floor along with the medieval collection and the protohistory (Iron Age to Romanisation). On the second floor are the modern collections as well as the Greek and Egyptian/Near Eastern collections, which I unfortunately did not have much time to view.

The section devoted to the protohistory of the Iberian Peninsula took up half of the first floor, which is where I started. While not Roman, I do have a particular soft spot for the Carthaginians as well local cultures immediately preceding Romanisation (and consequently the transitional periods between the two) , and this collection has both.

The Punic collection is not especially large, but contains a few nice pieces; including the so-called Lady of Ibiza, an ornately decorated 4th-3rd century BCE clay figure of Tanit. The Celto-Iberian part of the collection is, understandably, more extensive. All manner of objects are included; figures, ceramics, bronzes, jewelry, reliefs, inscriptions, and more.

The literal and figurative centerpiece of the Iberian collection is the reconstructed Mausoleum of Pozo Moro. The funerary structure, about 10 meters in height, is dated to about the end of the 6th century BCE and contains some blocks with relief scenes still remaining.

The Roman collection is, in a word, impressive. Not only does the collection contain some of the choicest pieces collected from sites around Spain, but also some pieces originating from Italy. The collection strikes a nice balance between aesthetically and historically interesting displays. The Roman mosaic collection in this museum alone is worth the price of admission.

But in addition to the mosaics, there are a host of large and small sculptural pieces, smaller bronze figures, both stone and bronze inscriptions (including several inscribed law codes), marble reliefs, and everyday objects.

One of the centerpieces of the collection is the mosaic depicting the twelve labors of Hercules. The scenes of Hercules take up about 2/3rds of the total mosaic, with the remainder being covered in a geometric pattern. The Hercules portion depicts a central panel of Hercules and Omphale, with the labors arranged in 12 panels surrounding this central scene. The mosaic dates to the 3rd century CE and was found at Llíria (Edeta), a site near Valencia that I would visit later in my trip.

Other themes represented on mosaics in the museum include charioteers, gladiators, the seasons, the Rape of Europa, the Muses, and Nilotic scenes.

Among a host of bronze legal and law tablets is the Lex Ursonensis, the municipal charter law of the Colonia Genitiva Julia (Urso, present day Osuna), awarded to the city in 44 BCE. The tablets were created between 20-24 CE and were originally comprised of 9 tablets, of which 5 remain and are displayed at the museum.

Another particularly intriguing inscription on display, this time in clay, is a letter between a dominus named Maximus to his assistant, Nigrianus. In the letter, Maximus describes an incident where Maxima, the lover of an estate manager named Trofimianus, in a fit of jealousy, beat a pregnant young slave so badly she died. For that, Maximus tells Nigrianus that Maxima must be punished for depriving him of two slaves. The clay tablet is dated to the 3rd century CE and was found in Villafranca de los Barros.

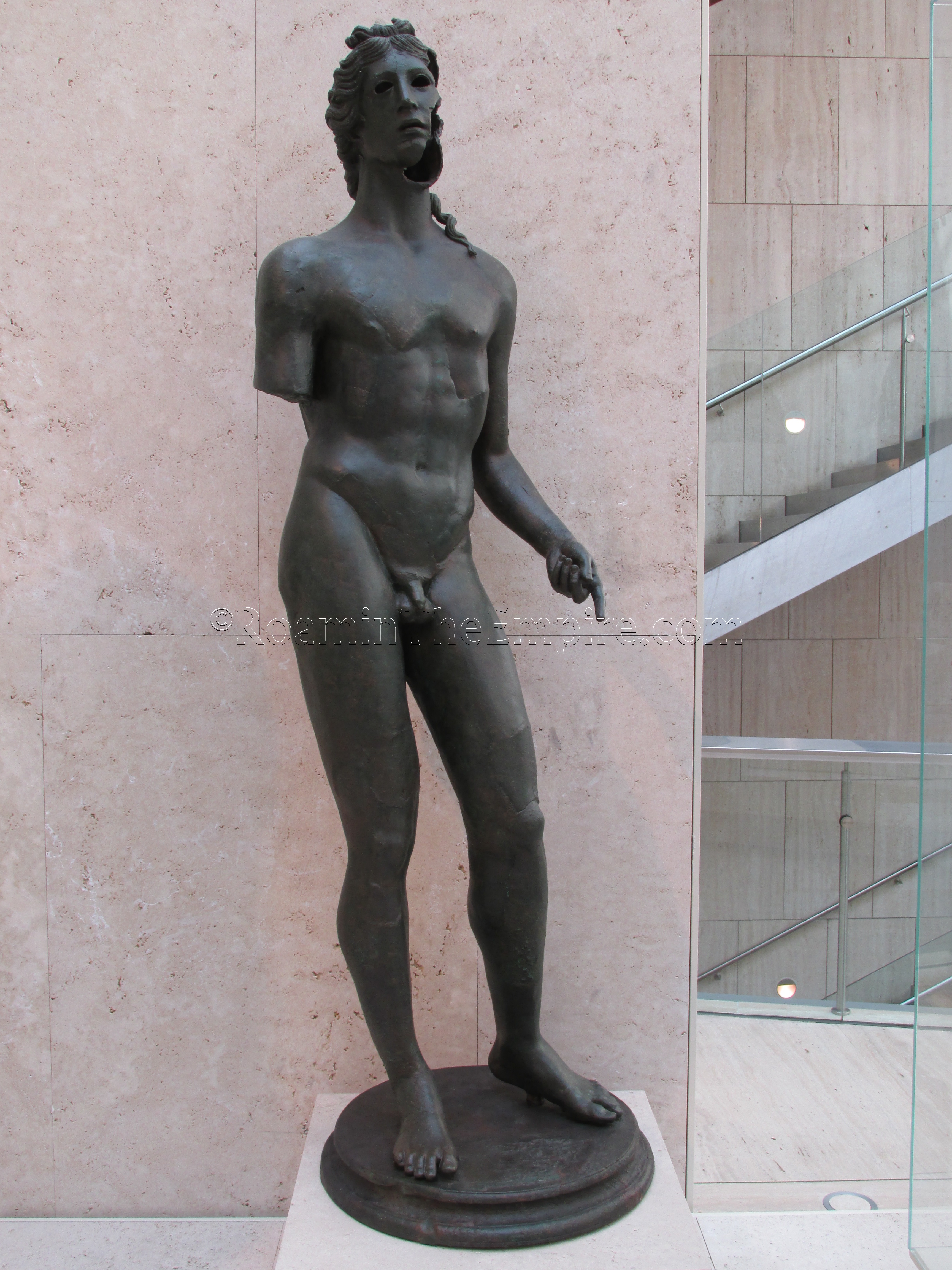

There was a fair amount of large statuary in the collection as well. While there was no shortage of the obligatory faceless togated statues, there was also a pair of seated statues of Tiberius and Livia Drusilla from Paestum, dated to the beginning of Tiberius’ reign. A large bronze statue of Apollo, dated to the 1st century CE, from Termantia (modern-day Montejo de Tiermes) was among the best of a sizable set of bronze artifacts.

While I certainly ran into some other very good archaeological museums in Spain, this is squarely among the best, as well a national archaeological museum should be. It’s not comparable to say, the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, but then it’s also fraction of the price of admission. Nearly every object is labeled in English (well-translated English too) and Spanish I spent a total of about 3 hours in the museum, which was enough time to take my time through the protohistory and Roman sections, and make a brief walkthrough of the prehistory section. I imagine another hour or so would have been ideal to see the Greek and the Egyptian/Near Eastern collections. At 3 Euros for the full-priced admission, it’s hard not to highly recommend this museum.

Sources:

Museum Placards

Museum Website