Most Recent Visit: June 2011

Quick Info:

Address:

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo

Piazza del Duomo, 23

56126 Pisa PI

Hours:

8:00-20:00 (April-September)

9:00-19:00 (October)

10:00-17:00 (November-February)

9:00-18:00 (March)

Admission: 5 Euro

Currently closed for renovation (2017)

Even in antiquity, the ancient precursor to Pisa was considered an “old” city. While that was agreed upon by classical sources, the exact origins of Pisae were a matter of some contention, though many sources also agree on a Greek origin. Sharing a name with a Greek site on the Peloponnesian Peninsula naturally lead to some comparisons between the two. Pliny the Elder attributed the foundation of the Italian city either to the mythical king of the Greek city, Pelops, or to the Teutani, a people of Greek origin. Strabo similarly traces the origins to the Greek city of the same name, but instead suggests that the Italian city was founded by settlers who had accompanied Nestor to Troy, and had wandered to Italy and founded the city on their way home from the Trojan War. Dionysius of Halicarnassus attributed the founding of Pisae to the Pelasgians and Aborigines, whom he also believed originated from the Peloponnesian Peninsula. Other writers also give the origins of those who founded Pisae as being Greek, though Cato notes that the city was founded by the Etruscans under Tarchon on a site previously belonging to the Teutani Greeks.

While there is no evidence of pre-Etruscan habitation, the presence of Etruscan graves in the area of the modern-day city would suggest that there was likely an Etruscan settlement at, or near, the location of Roman Pisae. Other than allusions to a founding by Tarchon, which would seem to indicate that Pisae was one of the twelve cities of the Etruscan League, not much is known about Pisae up until 225 BCE, when it first appears in the historical record. In 225 BCE, the consul Gaius Atilius Regulus brought his army from Sardinia, where he was combating a revolt, and landed at Pisae to meet a Gallic army marching through Etruria. That the Roman army would land there suggest that the city was already allied with the Romans in some capacity by that time.

Pisae seemed to become a primary embarkation point for Roman armies bound for Spain, Gaul, and Liguria. During the Second Punic war, Pisae was the departure point for Publius Cornelius Scipio when he took an army to Massilia to confront Hannibal as he marched toward Italy. It was also the return point when Scipio found he had missed Hannibal and had to return to Italy to prepare defenses. Continuing wars with the Ligurians also brought increasing importance to the city as a point for launching campaigns against the Ligurians. This also brought Pisae attention as a target of Ligurian aggression. Pisae was besieged by 40,000 Ligurians 193 BCE, though the siege was broken by an army led by the consul Quintus Minucius Thermus. There were evidently several other attacks in the territory of Pisae by the Ligurians in the following years, prompting the Pisans to seek additional protections under the Romans.

In 180 BCE, the people of Pisae invited the Romans to establish a colony, and the colonists were given Latin rights. Pisae was later given municipum under the Lex Julia. During the time of Augustus, it seems a new colony was sent to Pisae and it was given a new title, Colonia Obsequens Julia Pisana. After that point, Pisae seems to largely disappear from the historical record until after the decline of Roman power in Italy, though likely remained an important port, giving rise to its prominence in the medieval period. While Pisae was a river port on the Arnus (Arno) River, 2 and a half miles from the coast (now, 6 miles), there was also costal port, Portus Pisanus, located near present-day Livorno.

Getting There: Pisa is a relatively well connected city, and one can arrive there via nearly any means, including by air. Galileo Galilei International Airport, located within walking distance from the historic center of Pisa, takes flights from all over Europe, particularly the budget airline Ryanair, which has a large number of routes running in and out of Pisa. One year it was cheaper for me to take the train from Rome to Pisa, and fly out of Pisa to Dublin, rather than out of Rome. That being said, the train from Rome can take anywhere from 2 to 4 hours, and can cost between 20 Euro and 60 Euro each way, depending on the time of day (earlier trains seem to be cheaper and shorter). From Florence, the train is about an hour and costs 8.40 Euro each way. Both Florence and Rome have trains to and from Pisa at least once an hour, and as many as 5 times an hour in some cases. Buses run between Pisa and Tiburtina Station in Rome, and while a bit cheaper than the train (as low as 13.90 Euro each way if bought in advance), runs only twice a day (once on Tuesday and Wednesday) and takes in excess of 5 hours. Information on that route can be found here.

Given the city’s origins, the ancient remains in Pisa are surprisingly sparse. The only real standing remains to speak of are the so-called ‘Baths of Nero’. The remains of these baths are about 400 meters east of the Piazza dei Miracoli, along Via Cardinale Pietro Maffi. In a small piazza at the end of this street is a mostly extant octoganal laconicum from the baths (with a restored and reconstructed roof) as well as some fragmentary remains of the walls of the tepidarium, apodyterium and palaestra. The bathing complex doesn’t seem to have any actual connection to Nero, but was originally built in the late 1st century CE. An inscription (CIL XI 433) attributes a restoration of these baths in the 2nd century CE to a Lucius Venuleius Apronianus Priscus.

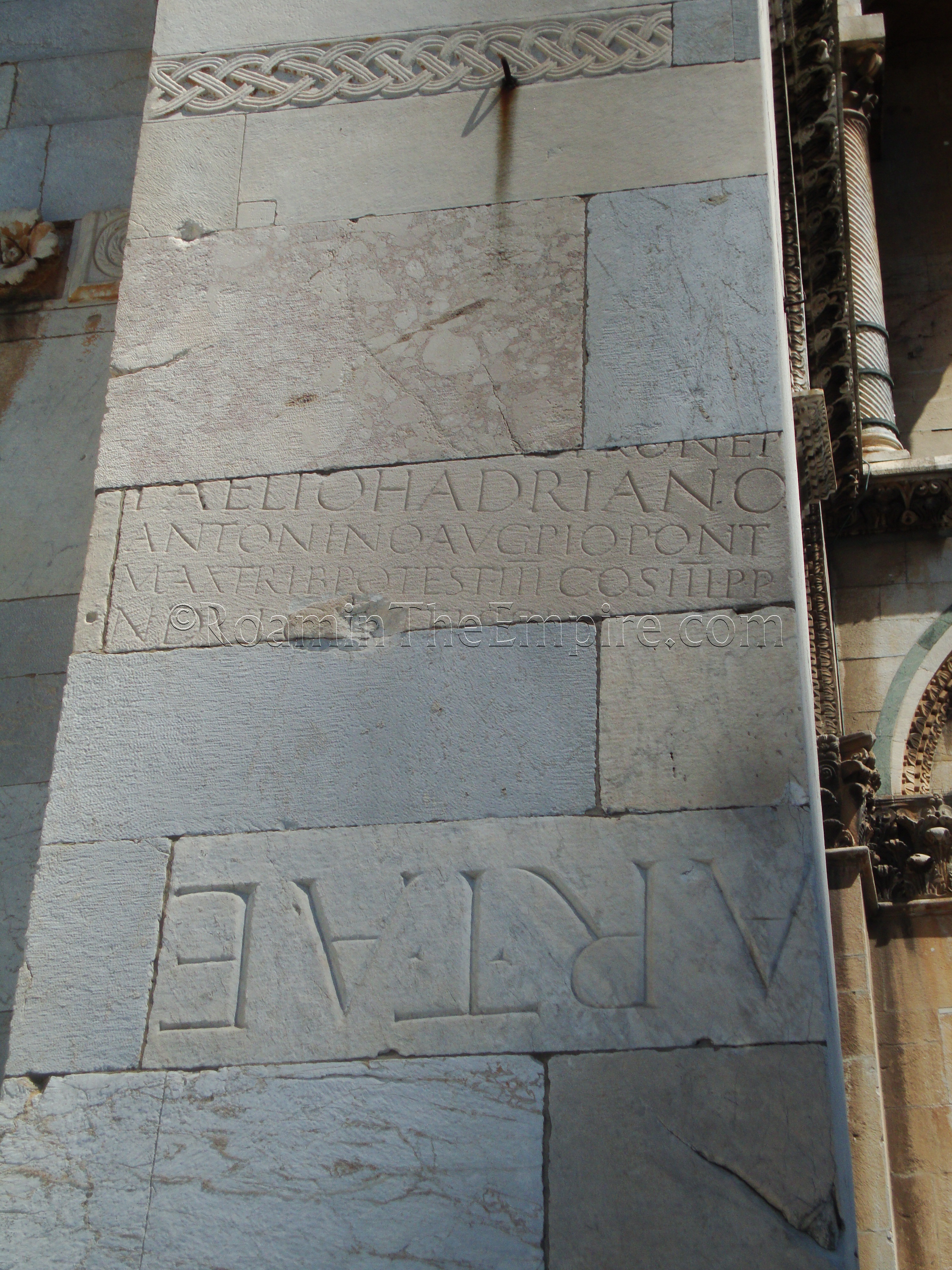

Back in the Piazza dei Miracoli, spolia from Roman constructions can be found used in the Cattedrale Metropolitana Primaziale di Santa Maria Assunta, and presumably the tower, though I did not personally observe any used there. The exterior of the duomo is faced with a sort of hodgepodge of marble fragments of varying origin, and a stroll around the exterior of the church will reveal a number of marble slabs that still have Latin inscriptions that are clearly from the Roman period. That being said, a vast majority of even the uninscribed marble slabs is likely spoliated from Roman constructions. I’ve seen some claims that some of this material came from as far away as Ostia and Palermo.

On the southwest corner of the Piazza dei Miracoli, adjacent to the Leaning Tower, is the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. While the vast majority of material in the museum is of medieval or later, there are a few Roman and Etruscan objects. Nothing is really groundbreaking, though. So, unless you have ample time to burn (perhaps waiting for an appointed time to go up the tower) or have a particular interest in the later material, the museum isn’t really worth the time for the ancient material.

In the realm of the very disappointing, is a perpetually closed museum devoted to the ancient ships found in the urban harbor of Pisae. Apparently as many as 16 ships dating to between the 1st century BCE and 4th century CE were found, with 9 of those being restored for display in the museum, which is supposedly housed at the Medici Arsenal, along the north bank of the Arno River, to the west of the Ponte Solferino. Though the actual museum may also be at a different location on Via Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli in the western part of the city, and pretty much cut off from the historic center by railway tracks. There appears to be several different ‘official’ sites that give conflicting information. One says that as of December of 2016, some of the ships in the process of being restored can be seen by appointment at the Medici Arsenal location. A different website says that the museum has been closed since July 2010, and is expected to open in 2013. It has not. Still, another, though not official, website gives a reopening date of the museum as 2009, which would seem to indicate the museum had been closed well before July 2010, or that it did indeed reopen in 2009, only to be closed again shortly thereafter. The ships were discovered in 1998, and since then, I can’t find any evidence that the museum, or the excavation/exhibition site at the Medici Arsenal, has been open for more than a few of the intervening years, if any. Should you be interested, the most recent incarnation of the official website seems to be here.

Sources:

Dennis, George. Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria Volume 2. London: John Murray, 1878.

Dionysus of Halicarnassus, Antiquitates Romanae, 1.20.

Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 21.39, 33.43, 35.3, 35.22, 40.1, 40.43.

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 3.8.

Scullard, H. H. A History of the Roman world: 753 to 146 BC. London: Routledge, 1980.

Strabo, Geographica, V.2.5.