Located in the northeast part of modern Bulgaria, the Roman town of Marcianopolis (present-day Devnya) seems to have originally began life as a Thracian settlement. It was later occupied by Hellenized settlers from Asia Minor and was named Parthenopolis. Roman Marcianopolis was founded about 106 CE, following Trajan’s campaigns in Dacia, to the north. The settlement was named after his sister, Ulpia Marciana. Legendarily, this occurred when Ulpia Marciana’s daughter was washing in a spring at this location, and the golden vessel which she was carrying with her to do so sunk down into the mud, disappearing below the surface. After a few minutes, the vessel resurfaced, and upon hearing of the strange occurrence, Trajan believed it to be the work of a deity that inhabited the spring. With that auspicious happening he decided to found a city there and name it after his sister.

At the crossroads between Odessos (modern Varna), Durostorum, and Nicopolis ad Istrum, as well as the location of plentiful springs, Marcianopolis became a strategically important settlement. A raid by the Costoboci in 170 CE necessitated the construction of fortifications around the city. Originally part of Thracia, it seems to have been incorporated into Moesia Inferior at the end of the 2nd century CE, following a period of particular growth. Marcianopolis was again the target of incursions from the north sometime around 248-250 CE when it was besieged by a Gothic force, perhaps under the command of Cniva, though it does not seem to have been taken. Again in 267 CE it was besieged by Visigoth forces, and once again was not taken.

The administrative reforms of Diocletian in the latter part of the 3rd century CE divided up Moesia Inferior into Moesia Secunda and Scythia Minor, of which Marcianopolis became and administrative capital of the former. It was at this point that Marcianopolis reached its most prosperous period through the middle of the 4th century CE. From 367 CE to 369 CE, the eastern emperor Valens used Marcianopolis as his winter quarters during campaigns against Visigoth incursions in the area. During this time it was denoted as being the temporary capital of the Eastern Empire.

Shortly after concluding peace, some Visigoths were allowed to settle in the area as foederati, but in 376 CE, after being exploited by local magistrates, the Visigoth settlers marched on Marcianopolis. A misunderstanding between the provincial governor Lupicinus and the Visigoth chief Fritigern led to a skirmish and then the declaration of war, kicking off the Second Gothic War. The first engagement happened between the forces just outside the city, resulting in a major defeat for the Romans; reportedly around half the army was killed. The city was sacked, but the remnants of the Roman army were noted as having sought shelter in the remains of the city following the battle. The city was sacked again in 447 CE by Attila the Hun.

Getting There: Devnya is not terribly far away from Varna (ancient Odessus), a popular summer destination and third largest city in Bulgaria, so that is the easiest place to start out from. Bulgarian public transport can be a bit tricky to navigate, especially to a smaller destination like Devnya. There does seem to be a few trains between Varna and Devnya daily. The trip takes between 45 minutes and an hour, and runs about 2-4 BGN each way, depending on the train and ticket class. The rail station for Devnya is a bit out of the center of town (though nearer to the little suburb of Devnya, Reka Devnya, in which the Roman remnants of the city are located than the main part of town), 1.5 kilometers, and goes through some sort of industrial areas that less intrepid travelers might be less enthusiastic walking through. Intercity bus line 14 apparently connects Varna and Devnya, though I couldn’t find any reliable schedules online. A car really is probably the best way to get from Varna to Devnya, as it’s a pretty straight shot right down the A2 and offers quite a bit more flexibility and peace of mind. Varna itself is well connected by train and has an airport that, particularly in the summer, hosts a number of flights from destinations around the Europe, mostly with low cost/budget airlines.

There are really only two points where remnants of the Roman city of Marcianopolis can be seen, though they’re both relatively close together. Again, they are notably in the smaller suburban hamlet of Reka Devnya rather than the main city of Devnya. The first of these points is the Museum of Mosaics (Музей на Мозайката) located at Pazarska Street 18 (улица Пазарска 18). In the summer (May through September), the museum is open every day from 10:00 to 16:00. The rest of the year, the museum is open Monday through Friday from 10:00 to 16:00 and is closed on Saturday and Sunday. Admission is 4 BGN.

The museum is essentially composed of two elements, the interior and the exterior. The museum itself is built on top of an insula that was entirely taken up by a late 3rd or early 4th century CE domus. The domus was constructed on an earlier building that seems to have been destroyed during the Gothic incursions in the middle of the 3rd century CE. The entirety of the four Roman roads that would have bordered this insula have been excavated and are visible around the exterior of the museum. As such, these can be seen without actually entering the museum and there does not seem to be anything limiting access outside the museum’s opening hours. A staircase leads down to the Roman street level and the roads can be traversed.

The northern of the two decumani actually cuts through the museum, but the entirety of it is visible in a tunnel that runs below the museum. A few architectural remains from the villa are also visible in this exterior portion of the museum. Most notably, near what would have been the center of the structure, now located right along the eastern wall of the museum, is what appears to be an atrium. A couple fragmentary columns have been found and placed upright in this area. A few other non-descript walls from the structure are also visible around the more well-defined atrium. On the western cardo, a section of the sewer is also exposed in the street.

Inside the museum are a number of both in-situ and relocated mosaics that decorated the domus, as might be expected given the name of the museum. There are also some finds from the area as well as some other structures excavated from the villa. The mosaics are obviously the highlight. Fortunately some of the better mosaics are in-situ and offer elevated viewing positions to get the best look at them. The mosaics that are not in-situ are sometimes too large to really appreciate when viewing them essentially at a ground level angle.

The most famous of the mosaics is a large, mostly intact floor of the triclinium that features a head of Medusa at the center of the rounded geometric Shield of Athena panel. This is one of the in-situ mosaics. The two other in-situ mosaics in the oecus area feature central panels of Zeus (as Satyros) and Antiope, and of Ganymede. Unfortunately, though also in-situ with good visual angles, both mosaics are pretty heavily degraded, making it difficult to pick out the subjects very clearly. For the Zeus and Antiope panel, however, the mosaicked names of the two figures is largely visible and legible.

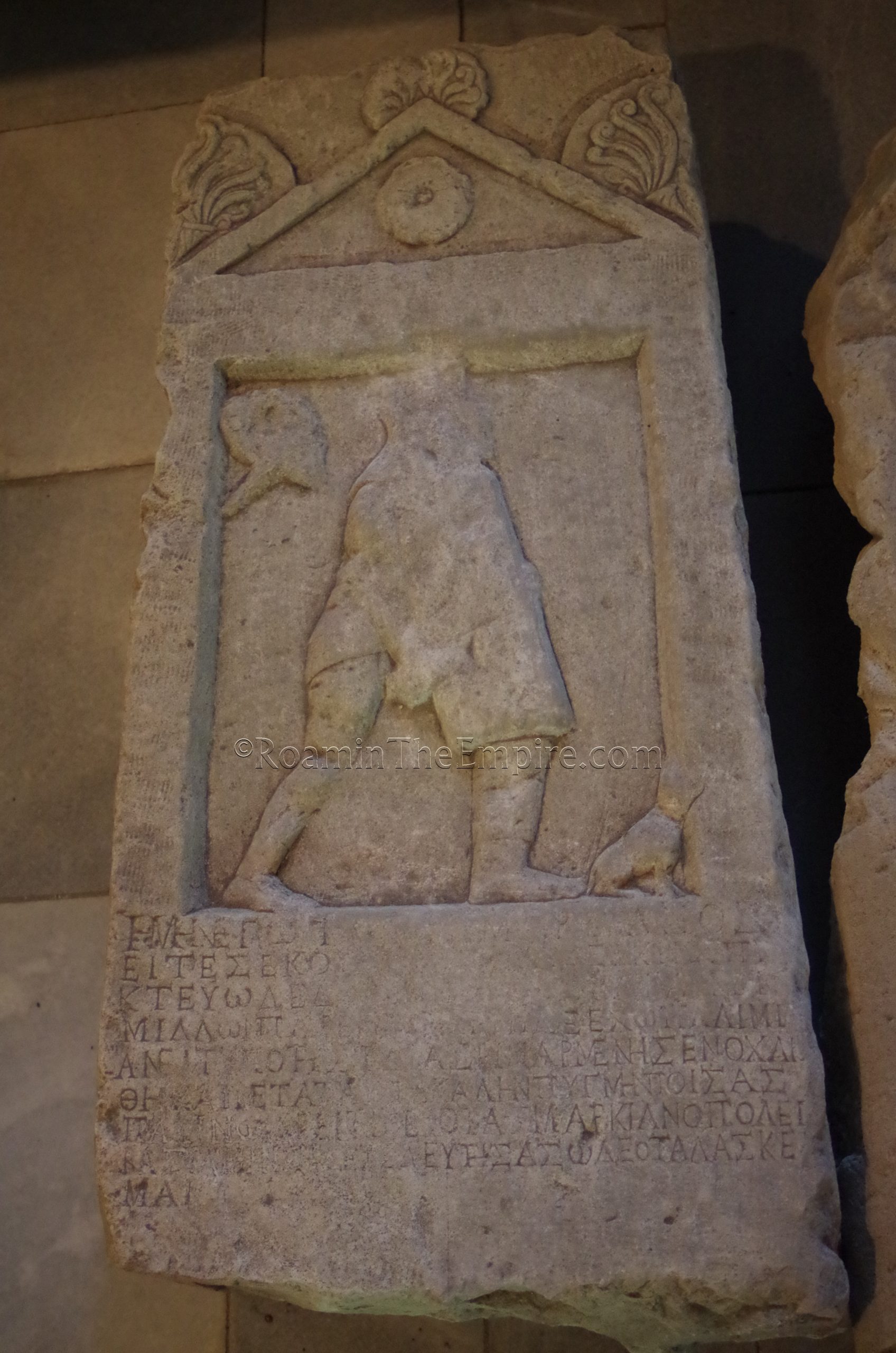

There are a few, mostly late antique geometric, mosaics displayed throughout the rest of the museum. One of the more interesting of these has depictions of animals and personifications of the seasons, though only that of Autumn remains as it is quite fragmentary. This is one of the mosaics not in-situ as well, so the views on it aren’t great. The natural lighting from windows coming in at angles, rather than from above, also makes it hard to appreciate some of these other mosaics. A number of artifacts are also collected from the excavations in the area, including some fragments of sundials and a few votive slabs and altars. Another particularly interesting find is the funerary inscription of a gladiator with a relief of the deceased in gladiator regalia.

A few areas of in-situ excavations can also be visited. These include a storeroom with small cell-like constructions and the so-called wine cellar with some fragmentary dolia intact and in-situ, which people have unfortunately taken to throwing coins into. The triclinium and oecus can also be seen from this area, though being at ground level and gated off, there’s really not much that can be seen.

It’s not an incredibly large museum, only taking about a half an hour to go through. But, the remains of the figural mosaics are perhaps among the best found in Bulgaria, so it’s well worth the stop. Even on a weekend at the height of summer, the museum was practically deserted both times I visited, adding a bit to the charm of seeing these mosaics someplace a bit off the beaten path.

About 350 meters to the northeast of the museum is the remains of the amphitheater. The first time I visited Marcianopolis, I couldn’t manage to find it. It’s definitely walkable from the museum, but, again, a car might offer the better alternative if one is available; even though it is a sort of roundabout and mildly confusing route to get there, as not all the roads in this area seem to be plugged into GPS/Google Maps. The amphitheater itself is mostly fenced off, though there are some pretty obvious bypasses that have been made and allow access.

Not a whole lot of information is available on the amphitheater. It may have been constructed in the late 2nd or sometime in the 3rd century CE. The structure seems to have consisted of 12 rows of seating, with all but the foundations gone except for some bits of the rubble core at the porta libitinensis (northern gate). Apparently modern gladiator festivals are held here from time to time, so there are some modern tent-like constructions around the arena of the amphitheater, mostly looking a few years old with tattered cloth coverings when I visited in 2019. One bit of inscription, apparently one of the inscribed names of the amphitheaters patrons or honored guests, is laying around and visible on site.

There’s not a whole lot to see here, it is interesting. Given that most of the amphitheater is at ground-level foundations with modern stuff overlaying a lot of it, it’s a very quick stop. And it can mostly be seen from outside the fence, should taking one of the bypasses not be to everyone’s liking. Interestingly, when looking at the amphitheater from satellite imagery, it is distinctly not perfectly oval, something that can’t really be appreciated from the ground.

Marcianopolis is an interesting little half a day trip from Varna. The trip (if using a private car) is really only a couple of hours including driving. The mosaics are really worth making the trip for, while the amphitheater is interesting, but not spectacular or very time consuming.

Sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus. Reerum Gestarum, 24.4.12, 27.5.5-6, 31.5.4, 31.8.1.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Jordanes. De Origine Actibusque Getarum, XVI.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Zosimus. HIstoria Nova, 1.42, 4.10.