History

Scattered among the bustling modern capital of Sardinia are the remains of the Punic and Roman city of Caralis. The favorable geography around Caralis attracted habitation in the area dating back to the Neolithic age. Sometime in the late 8th or early 7th century BCE, the Phoenicians established a colony here called Karaly, one of several the traders founded on the island. Little is known about the city prior to the Roman arrival on the island, but in the late 6th century BCE, Sardinia fell under the hegemony of the Carthaginians. Sardinia saw little fighting during the First Punic War, and it was not originally included in the Carthaginian territorial concessions to Rome. A mercenary revolt shortly thereafter, though, gave Rome the opportunity to annex Corisca and Sardinia, along with Caralis, from the Carthaginians in 238 BCE.

During the Second Punic War, Caralis served as a base of operations for the Roman praetor Titus Manlius Torquatus. In 215 BCE a local Sardo-Punic landowner named Hampsicora led a revolt in the still heavily Punic southern and western parts of the island. Torquatus set his army out from Caralis to Cornus, and after first beating an army of rebels led by Hampsicora’s son Hiostus, Torquatus withdrew back toward Caralis after a Carthaginian army landed at Tharros to support the revolt. A second battle took place near Caralis, at the site of modern Decimomannu, to the north of Caralis. A decisive Roman victory, the capture of the Carthaginian general, and the death of Hiostus put an end to the revolt. Hampsicora is said to have committed suicide shortly after.

The Roman settlement of Caralis originally grew up separate from the old Punic center of Karaly, perhaps giving rise to the plural name that Caralis was sometimes referred to; Carales. Eventually the two population centers merged into a single urban area in the 2nd century BCE. During the civil war between Caesar and Pompey, Caralis declared loyalty to Caesar (whose fleet stopped in Caralis on the way back from Africa), and remained loyal to Octavian in the subsequent war between him and Pompey’s son. When Sextius Pompey’s general, Menas, captured Sardinia, Caralis was the only city on the island that had to be subjugated by force.

By the 1st century CE, Caralis had effectively become the capital of Sardinia. Though it never gained the status of a colony, it was afforded municipium, probably during the reign of Augustus. Caralis served as a major naval base for operations against the Goths and Vandals in the 5th century CE, but fell to the Vandals along with the rest of Sardinia in the latter half of that century.

Getting There: Cagliari is the main city on Sardinia, and as such it is the main transportation hub for the island. There are ferries between Cagliari and both Sicily and mainland Italy, and there is an airport that hosts flights from around Europe. Once in Cagliari, the city is relatively walkable, and most of the sites discussed are within a 15 or 20 minute walk of the center.

Area Archeologica di Sant’Eulalia and Cripta di Santa Restituta

The first stop is the Museo del Tesoro e Area Archeologica di Sant’Eulalia, a treasury museum and archaeological area attached to the Chiesa di Sant’Eulalia. The entrance to the archaeological area is located at a separate entrance at Vicolo Collegio 2. The treasury museum and archaeological area are open 9:30 to 16:00 from Tuesday to Sunday. It is closed on Mondays and admission is 5 Euros.

The treasury museum is mostly religious artifacts from later periods, but the archaeological area contains remains from both the Punic and Roman periods, as well as later religious structures. During the Punic period, the space was a religious sanctuary on the outskirts of Karaly, and part of the space in this archaeological area seems to have continued to be used for religious function into the Roman period. This space is visible when first entering and heading toward the right, and while many of the elements date to the Roman period, the core is Punic in nature, and consists of a treasury area and an open air pit.

Further on is a monumental portico that dates to the 3rd or 4th century CE. Interestingly, many of the roofing tiles that were used on the portico seem to date to a much earlier period, between the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE, suggesting they were re-used. This area also includes a 6 meter deep cistern that later seems to have served as a treasury of some sort. The lack of coins found beyond the first half of the 5th century CE might indicate that it was used for safekeeping at the onset of Vandal raids. A small collection of artifacts is kept in cases in the area of the portico.

There are a number of constructions dating to the post-Roman period in the area past the portico, as the circuit begins back toward the entrance. Back at the entrance area, though, there are the remains of Roman road paving dating to the 4th century CE. The walls that border this road seem to date a few centuries later, though, as are some of the adjacent constructions. There are a few informational signs with English translations that help the visitor to try and make sense of the somewhat complicated layers of occupation and what structures are associated with which period.

About a 10 minute walk to the northwest is the Cripta di Santa Restituta, at Via Sant’Efisio 8. The crypt is open every day between 10:00 and 19:00. Admission is 2 Euro. A combination ticket can be bought that also allows access to the Villa di Tigellio and the Grotta della Vipera for 6 Euros (more on those sites later, but, I’d advise against the combo ticket based on my experience). This space was originally a Punic limestone quarry that made use of an existing natural cave, and some finds have suggested it possibly functioned in a religious site following the quarrying activity. In the late Republic and early empire, the space was used for amphorae storage. In the late 3rd or early 4th century CE, the cave was supposedly the place of martyrdom of a woman named Restituta, and from that point became associated with Christian veneration of the saint, as it is today.

From the Cripta di Santa Restituta, it is about a 15 minute walk, most of it uphill, to the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari, located at Piazza Aresenale 1. The museum is open between 9:00 and 20:00 daily, year round, except for Mondays. Admission to the museum is 7 Euros for the standard admission, though persons 18-25 years of age can enter for 2 Euros. Admission is also free to the museum on the first Sunday of each month.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari

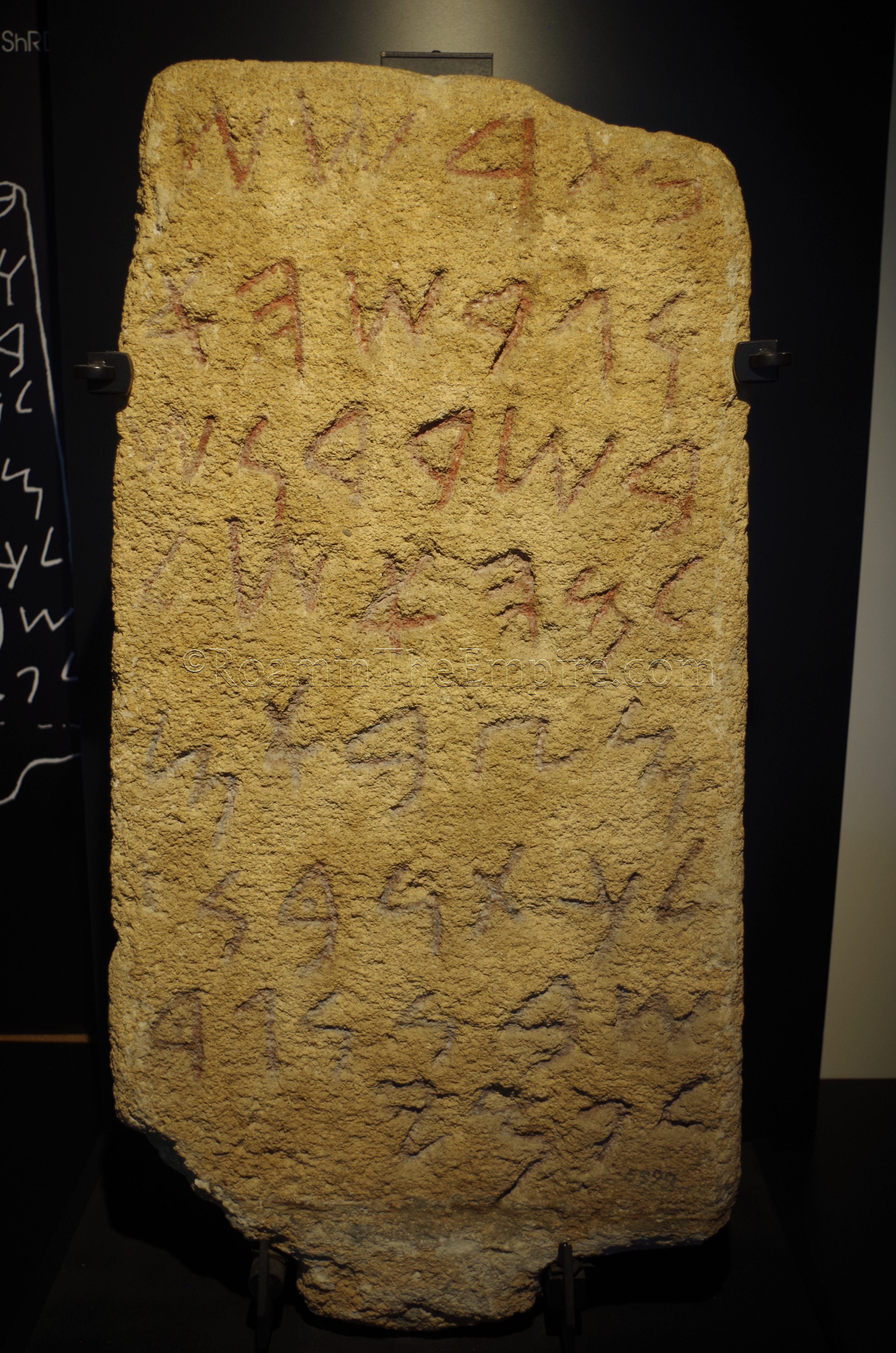

The Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari is the primary archaeological museum for the island of Sardinia, and as such, the collection spans artifacts not just from the Cagliari region, but from across the island. The museum’s collection is heavy in pieces from the Nuragic and pre-Nuragic civilizations that inhabited Sardinia, but there are still strong showings from the Punic and Roman eras. The Punic pieces consist mostly of small terracotta statuettes and figures as well as funerary stones. One of the more important Punic pieces is the Nora Stone, a Punic inscription found at nearby Nora and dated to the late 9th or early 8th century BCE, making it the oldest Punic inscription found on Sardinia. The inscription commemorates the victory of a general over the local Sardinians, and may make reference to Pygmalion, the king of Tyre during that time period.

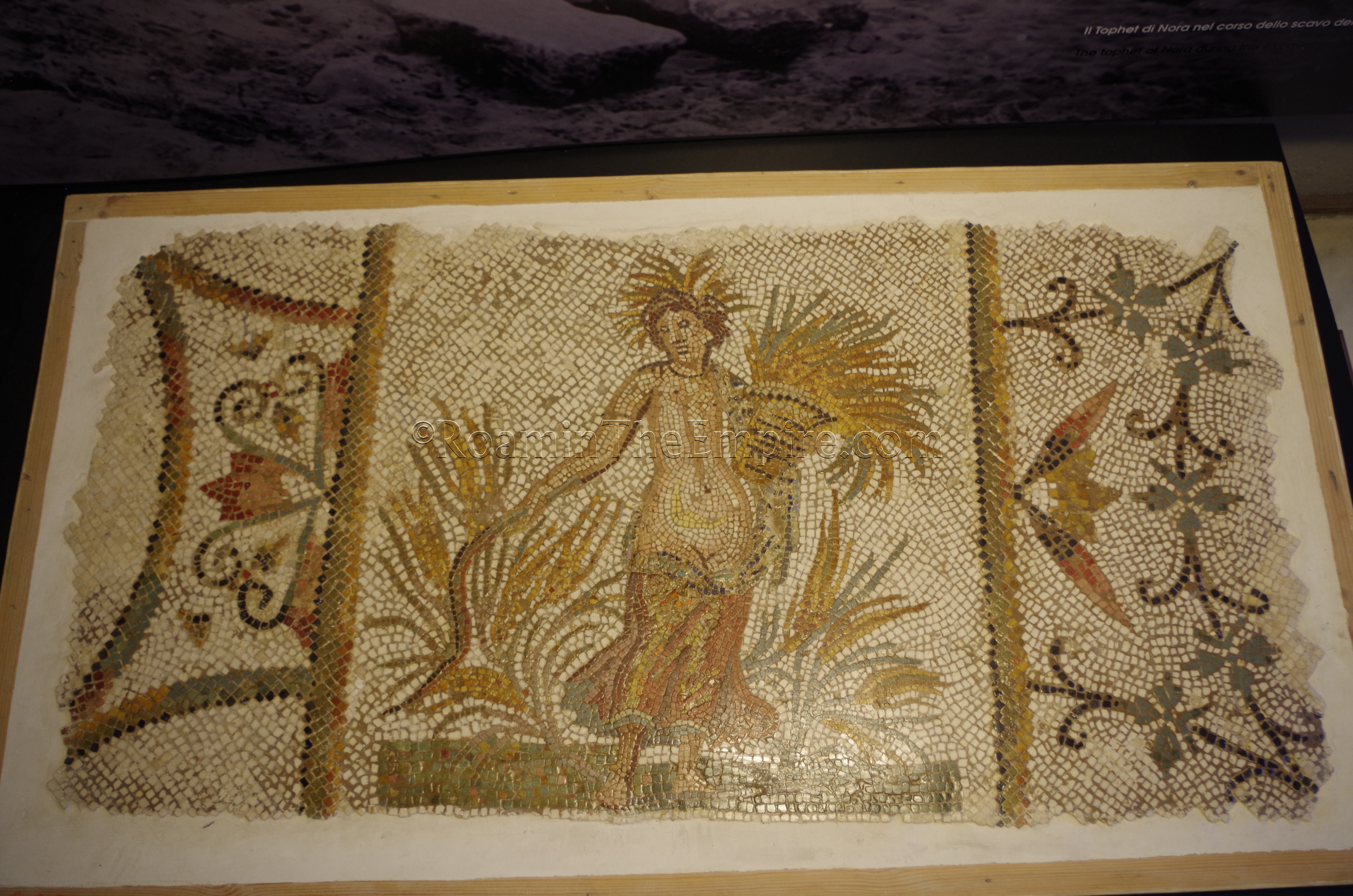

The Roman finds presented at the archaeological museum run the spectrum of what one would expect to find at most museums. There are a number of large, marble statuary pieces and smaller portrait busts. A few nice examples of mosaic are on display as well. There are a few inscriptions in the collection inside the building, but all of the larger funerary inscriptions are displayed in an exterior garden accessible next to the main entrance of the museum. There are some smaller terracotta pieces and smaller statuettes in addition. A few of the statuary pieces are quite nice, as are a couple of the figural mosaics, but, again, the centerpieces of this museum are in the pre-Roman collections. Interestingly, there are several pieces sourced from Tunis and the Bardo Museum, which are probably among some of the nicer Roman objects.

Most artifacts have descriptions and information in both Italian and English. Overall, the museum is quite large, it took me the better part of 3 hours to get through the entire collection. As it is the primary archaeological museum on the island, it’s certainly worth the stop and offers a good overview of occupation on the island, as well as the immediate area of Cagliari.

Amphitheater

Not far from the archaeological museum is the Roman amphitheater of Caralis, located off Via Sant’Ignazio da Laconi. The amphitheater is open from 10:00 to 19:00 in the summer, and from 9:00 to 17:00 in the winter. It is open every day. Admission to the amphitheater is 3 Euros, though combined tickets with other sites in Cagliari are available.

The amphitheater of Caralis was constructed in the 2nd century CE, and is rather unique in that about three quarters of the amphitheater is carved out of the living rock of the hillside. The seating of the cavea is carved directly out of rock, and the galleries of much of the amphitheater are carved through rock. Only the southern extent of the amphitheater was built of freestanding stone, none of which remains intact, as the limestone blocks were spoliated for building material post-antiquity. The corridor cut out of the rock leading north apparently connects to an underground cistern-like structure that was used as a prison.

It should be noted that when I visited the amphitheater (June 2019), it was in the midst of renovations that largely limited access, and this seems to be a project that will last several years. Access was limited to a ramp that lead down a little closer and gave a little bit better view of the interior of the amphitheater. Despite this limit, the admission was still full price. There were some informational signs near the ticket stand. It’s a bit disappointing that there is no real access to the amphitheater despite the entrance fee, but, hopefully the restoration and renovation project will allow that in the future.

Sources:

Julius Caesar. African War, 98.

Cassius Dio. Historia Romana, 48.30-31.

Dyson, Stephen L. and Robert J. Rowland Jr. Archaeology and History in Sardinia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, & Conquerors. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2007.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictioniary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997.

Hoyos, Dexter. The Carthaginians. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Livy. Ab Urbe Condita, 23.40-41.

Miles, Richard. Carthage Must Be Destroyed. New York: Viking, 2011.

Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia, 3.13.

Pomponius Mela. De Chorographia, 2.123.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Strabo, Geographica, V.2.7.