The environs of the Roman settlement of Serdica (modern Sofia, Bulgaria) seems to have been inhabited at least as early as the 3rd millennium BCE, the date of the first significant settlement found in the area. Though occupation may date back much further. The Thracian population group, the Tilataei, established a settlement at the site of Serdica (possibly called Serdica or some derivative at the time) sometime in the 6th century BCE. Upon the foundation of the Odrysian Kingdom in the early 5th century BCE, Serdica was incorporated into that political entity. Serdica was sacked by Philip II of Macedon around 340 BCE during his conquest of the Odrysian Kingdom.

At some point between the 4th and 1st centuries BCE the Serdi population group emerged, perhaps taking their name from the city of Serdica around which they were centered, or alternatively the name of the settlement deriving from the people. The circumstances of their emergence is not completely clear; they are sometimes described as being a Celto-Thracian group resulting from the Celtic migrations to the area in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, but alternatively surmised to be perhaps even strictly Thracian in origin. The Serdi don’t appear in the historical record until about the middle of the 1st century BCE, shortly before the Roman conquest of Serdica.

Roman conquest came in 28 BCE, when after conducting campaigns against the Bastarnae in Scythia, Marcus Licinius Crassus (grandson of the famous triumvir of the same name) was attacked by the Serdi and Maedi passing through the area on the way back to Macedonia in 29 BCE. He returned the following year to pacify those populations and subsequently conquered Serdica in the process. According to Cassius Dio, he had the hands of the prisoners of the campaign cut off. Serdica did not remain under direct Roman control, though, and was administered by the Odrysian client kingdom until the creation of the province of Thracia in 46 CE. It became an important settlement, notably on the road between Naissus (modern Niš, Serbia) and Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv) and near the source of the Oescus (modern Iskar River), a tributary of the Danubius (Danube). During the reign of Trajan, the city was elevated to municipium and given the name Ulpia Serdica.

Serdica was sacked during the Costoboci invasion of the Marcomannic Wars about 170 CE, resulting in the construction of robust fortifications in the following decade. During the third century CE, two emperors were born in or around Serdica; Aurelian in 214 CE and Galerius in 258 CE. Gothic raids resulted in another sack of the city around 268 CE. After Aurelian abandoned Dacia in 271 CE, Diocletian subsequently broke Thracia up into a number of new provinces, one of which Serdica was appointed as the capital; Dacia Mediterranea. The city rose to great prominence in the 3rd and 4th centuries, with Constantine apparently considering making the city an imperial capital and Galerius issuing the Edict of Serdica, abolishing Christian persecutions in 311 CE, shortly before he died there as well.

In 343 CE, the Council of Serdica (or Synod of Serdica) was held in the city to attempt to reconcile the Arian controversies. Attila the Hun sacked the city once again in 477 CE, but it was later reconstructed under Justinian I and flourished as a Byzantine city through the 9th century CE.

Getting There: Sofia is the capital of Bulgaria, and therefore is pretty easily accessible from most parts of Europe by plane. Regionally, it is connected to other major cities in the country and the wider Balkans by bus and rail (fair warning, though, the trains are quite slow, but are also very affordable). Once in Sofia, it’s a relatively large city, but it’s actually quite walkable. Most of the Roman remains are located in a fairly small area in the very center of the city. There are a few outliers, but even those aren’t really very far out from this centralized location.

The first stop is the Saint Sophia Church, located at ul. Paris 2. The main part of the church is open from 9:00 to 17:00 daily and is free. Saint Sophia Church has an interesting history in and of itself. The church that stands today is noted as being the oldest in the city and is alternatively dated to somewhere between the 6th and 7th century CE. This church was built upon an earlier churches that dates back to the 4th and 5th centuries CE. It is at this 4th century CE church that the Council of Serdica supposedly met in 343 CE. Prior to that, the location served as a necropolis. After the 4th century CE church was destroyed, possibly in Attila the Hun’s sack of the city in 477 CE, it was then rebuilt, perhaps under Justinian I’s general rebuilding of the city.

Beneath the church and accessible through the crypt are some of the remains of the earlier 4th century church and the necropolis. To visit the crypt requires a ticket costing 6 BGN, and the hours are a little unpredictable. There doesn’t seem to be really any set hours, just whenever someone is available to let people down into the crypt. I tried to go in the morning, but was told it would only be open in the afternoon that day. It was worth the wait and having to track back to it later. There are the remains of several tombs, mostly dating to the 4th century CE, but also a few dating to the 3rd century CE. One, in particular, has an interior with fairly intact fresco decoration dating to perhaps the latter half of the 4th century CE. Again, there are also some remains from the earlier incarnations of the church, specifically the mid-5th century CE church, and including a few mosaics (though one, at least, is seemingly a copy as the original is in the archaeological museum).

A few blocks west at ul. Budapeshta 4 are the remains of the amphitheater of Serdica. Now, these remains are actually located inside the Arena di Serdica Hotel, whose construction in 2004 led to the discovery of the amphitheater. There is no actual admission, you can just walk into the hotel and take the elevator down to the remains, which are also visible from the foyer of the hotel. Since it is a hotel, it is presumably ‘open’ all the time, but, it is probably best to visit during kind of standard daytime hours. The area also serves as kind of a reception and gallery area, so it will presumably be unavailable to visit during events.

Serdica’s amphitheater seems to have been built in the 3rd century CE with another phase of construction/renovation dating to the 4th century CE. Interestingly, it was built on top of a theater that was constructed in the 2nd century CE and then destroyed in the Gothic sack of the city in 268 CE. The amphitheater seems to have been in use until the 5th century CE when it was abandoned. Capacity is estimated at about 20,000-25,000 spectators. Originally about 60 meters in length, only a small portion of the amphitheater is uncovered and visible, though that does include the distinctive curvature of the arena portion of the amphitheater. One interesting detail is the display of a tile with dog paw prints embedded before it had set.

Another few blocks to the west, among the core of the archaeological remains of the Roman city, is the National Archaeological Museum of Bulgaria. The museum is located in the building of the former Grand Mosque of Sofia at ul. Saborna 2. During the summer (May through October), it is open every day from 10:00 to 18:00. The rest of the year the museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10:00 to 17:00, and closed on Mondays. Admission is 10 BGN.

As one might expect for the national archaeological museum of a country, the collection here is pretty significant and spans the entirety of the country, rather than necessarily focusing on local material. Outside, in front of the museum, there is a small lapidary garden with a few inscriptions and architectural pieces. Inside, the collection spans the material history of Bulgaria, with a small section of artifacts dating back to from the Paleolithic through the Bronze Age. The main hall of the museum, which takes up the entirety of the first floor is devoted to the Thracian, Greek, and Roman periods throughout Bulgaria, with the Roman period probably composing the largest portion of the collection.

The main collection boasts a pretty significant number for votive plaques, primarily of imperial Roman dating, but depicting a number of different gods in the Roman, Greek, and Thracian pantheons; a terrific example of the nature of religion in an area with so many strong influences. There is a pretty broad collection of funerary stele with portraits of the deceased as well; many depicting entire families. These too seem to date primarily to the Roman imperial period.

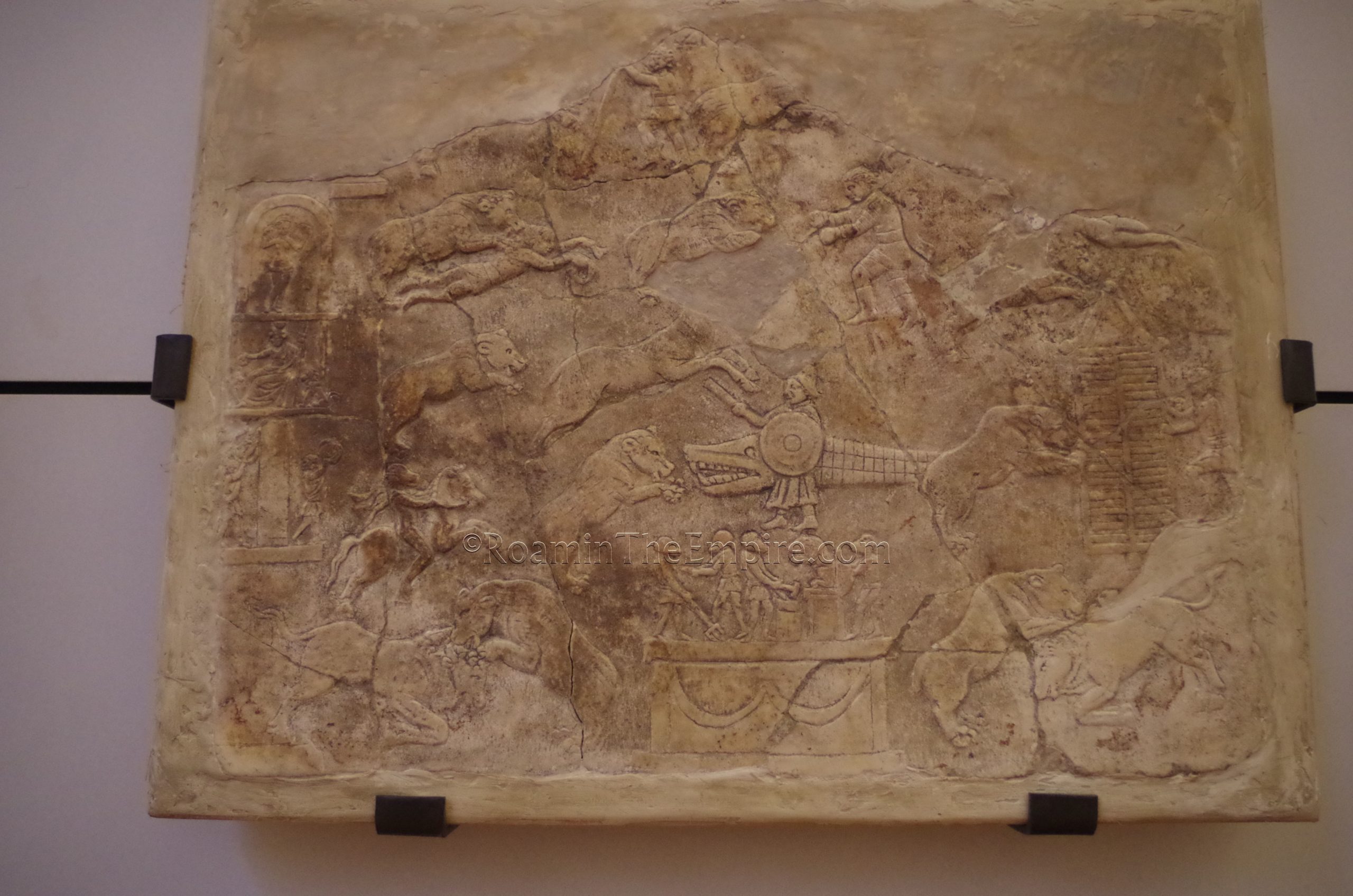

There are a number of other interesting finds; some statuary and a lot of smaller bronze figurines as well as a few fragments of larger bronze pieces. One particular interesting piece is a mensa ponderaria, a slab with standardized measurements for marketplace transactions. There’s also an interesting relief depicting venationes, interpreted as perhaps an advertisement for the hunts taking place in Serdica’s amphitheater. In addition, there are also a few mosaics and wall paintings associated with early Christian buildings and tombs.

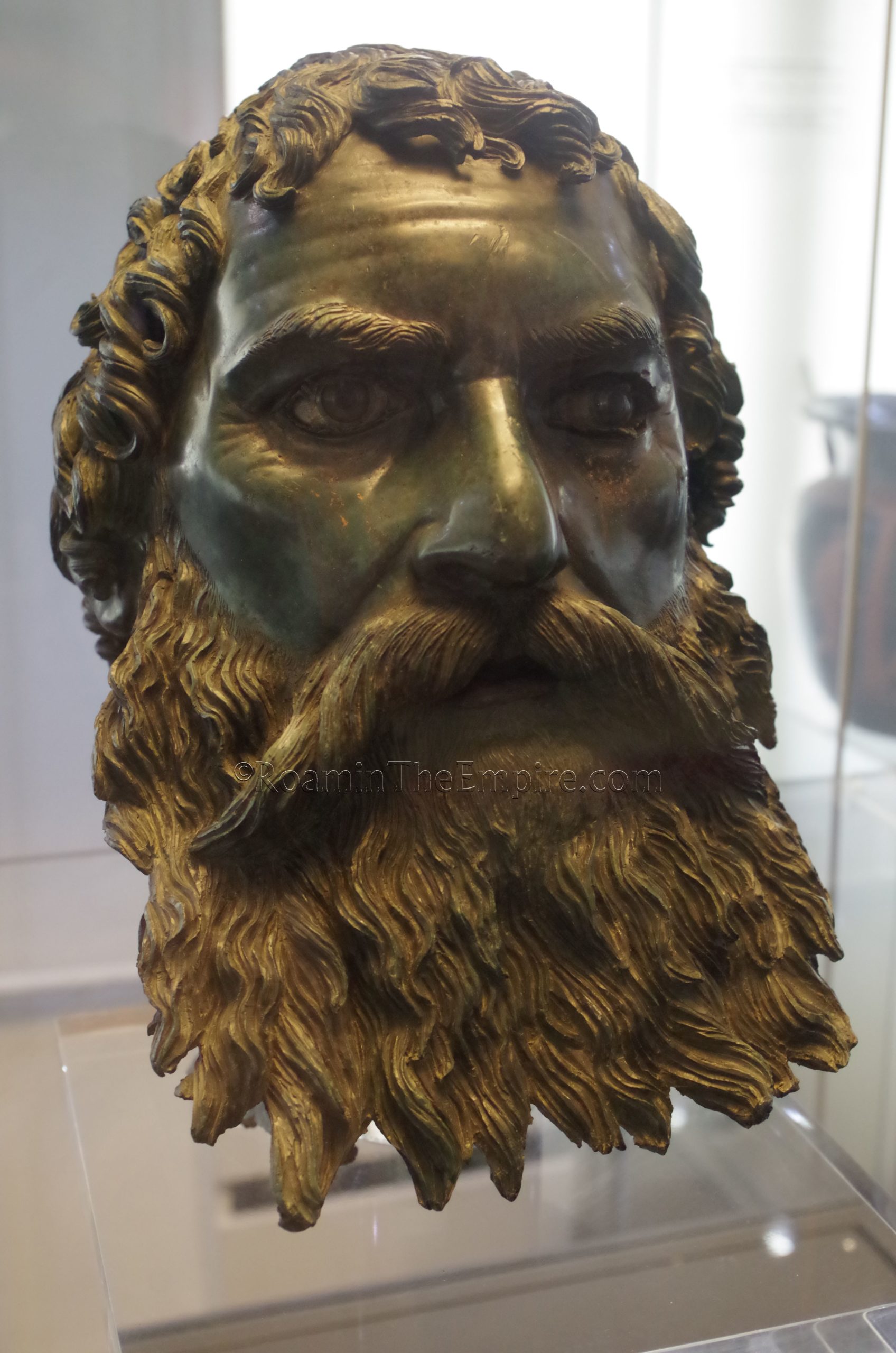

The upper floor mostly contains later post-antique finds, though the treasury is also located on the second floor. This contains coins, jewelry, and other objects made of precious metals dating throughout the historical periods. There’s some ancient material, though it is mostly Greek and Thracian in origin. Among this collection is a particularly striking bronze bust with alabaster and glass eyes, dating to the end of the 4th century BCE. The museum is fairly large, and I easily spent in between 2 and 2.5 hours there. While I did briefly walk through some of the pre-Thracian and post-antique sections, the bulk of my visit really was focused on the Thracian through Roman period materials.

From the archaeological museum, it’s a short walk across the street to the Church of St. George Rotunda, enclosed in the courtyard of a large building that houses Bulgarian governmental agencies and a hotel. The church, consecrated in the 6th century CE, is housed within a 4th century CE rotunda that was constructed as some kind of public space, though the exact usage is unclear. It was initially identified as part of a bathing complex, but that has subsequently proven to be unlikely. The church is still functioning, and at times it is inaccessible due to services, but is generally open between 11:00 and 17:00 daily, with no admission (though donations are solicited). Additionally there is no photography allowed inside the church. Some additional walls immediately surrounding the church are dated to varying periods, and the dome of the church itself has been rebuilt a few times, so that element is not an original Roman construction.

On the east side of the church, however, is an archaeological complex that is accessible via a staircase on the north side of the excavations, just east of the church. There doesn’t seem to be any sort of gate that limits access, so it is presumably accessible at all times. The courtyard, too, does not seem to have any sort of limitation of access. What remains in this excavated area adjacent to the Church of St. George Rotunda is a fairly well preserved/conserved stretch of a cardo running north-south along the site. This road separates the church from another building; the remains of a bathing complex. This bathing complex seems to date to perhaps the 2nd century CE.

The walls of these baths have some pretty heavy handed conservation, but, that seems to be a pretty common tactic with some of these sites that are just kind of open to the public without any real kind of supervision. A few of the rooms have some remains of hypocaust systems, including a small reconstruction in the corner of one. The far rooms along the eastern side are also apsidal and in the middle an unusual octagonal room, which earns the complex its distinction of sometimes being referred to as the building with the octagonal room. Unfortunately there’s not really anything in the way of information on site to contextualize the remains. There’s a small engraved stone that notes in Bulgarian and English that these are, in fact, baths, but that’s about it. It’s still very much worth the stop and the raised square around it offers some great overviews of the baths.

Sources:

Ammianus Marcelinus. Rerum Gestarum, 16.18.1, 31.16.

Cassius Dio. Historia Romana, 51.25.

Eutropius. Breviarium ab Urbe Condita, 9.22.

Grant, Michael. A Guide to the Ancient World: A Dictionary of Classical Place Names. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997

Paunov, Evgeni I. “Roman Entertainment in Sеrdica-Sofia.” Minerva, vol. 19, no. 2, 2008, pp. 40–41.

Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Walton & Murray, 1870.

Stillwell, Richard, William L. MacDonald, and Marian Holland. McAllister. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U Press, 1976.

Valeva, Julia (ed.), Emil Nankov (ed.), and Denver Graninger (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Thrace. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.